Malaria, the invisible disease

ICREA Research Professor

- Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. It is preventable and curable.

- The name malaria comes from the Italian for “bad air”. In the past, people thought that malaria came from the air emanating from ponds or from stagnating water.

- About a century ago, we had malaria in most places of the world. Today, malaria is mainly transmitted around the tropics, which is why most people think that malaria is a typical tropical disease. This is a misconception: malaria is a “man-made” tropical disease.

Imagine you are in rural Africa…

We are in a rural area, in a village, in any sub-Saharan African country. A young child, often under the age of five, more typically one or two years of age, gets bitten by a mosquito. Most likely, they will get bitten during the night because that’s the typical time for mosquitoes to transmit malaria bites.

The child gets bitten. Nothing happens for a few days. After a couple of weeks, the child develops a fever. That’s the most typical first sign of malaria because malaria mainly causes a fever.

When the fever appears, the mother of that child can do two things. She can take her child to receive healthcare or she can ignore the fever and hope it will go.

They can go to the doctor, to the health system or to a traditional healer, which is very typical in rural African areas. If the child is lucky enough to receive the drug that cures malaria, they will be cured.

But if the child does not receive the drug that cures malaria, the disease will very quickly progress and become a life-threatening infection. In a matter of a few hours or a few days the disease can kill the child.

So, it’s a matter of receiving the drug that can save you or not receiving it.

Of saving your life or not saving it.

A real threat to mankind

Malaria can be considered one of the world’s biggest killers and a real threat to mankind. In fact, it’s one of our oldest diseases.

We have documented malaria infections in the mummies of ancient Egypt. Malaria has killed popes, kings, presidents – a truly democratic disease! Malaria has been with us forever, for millennia.

Although the malaria burden has been dramatically reduced in recent decades, we still see one malaria-associated death every two minutes. A child dies of malaria every two minutes.

I say we see this, but actually we don’t. We just see it in those places where malaria is still transmitted.

A huge burden

We believe there are about 220 million clinical cases of malaria every year. Malaria is transmitted in nearly 90 countries, and around 500,000 people die of malaria every year. Imagine how big the burden is. That is 1,400 people every day, or the equivalent of a 9/11 occurring every other day. It’s not only a question of how big the burden is, it’s also where the problem is concentrated.

The problem is heavily, disproportionately, concentrated in a few places, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where 9 out of every 10 cases of malaria occur, where 9 of every 10 deaths due to malaria occur.

In some areas of the world, children can get up to one episode of malaria every month of their lives. That’s unheard of! Can you imagine what our reaction would be if a potentially life-threatening disease could strike our children once a month?

Intermittent fevers

For centuries, people knew that intermittent fevers were caused by malaria. But they did not know what was behind it.

They were called tertiary fevers, or quaternary fevers, because they would reappear every third or fourth day. It was not that the mosquito would bite you every three or four days, just that the symptoms – “the fever” – would reappear. And the reality is that at that time, people didn’t know what was happening.

The term malaria – from mala aria, the Italian for “bad air” – is recent. In French-speaking countries, it was called paludisme because it was believed that malaria, or paludisme, came from the stagnating waters from the paludes, the Latin for swamps or marshes.

The characterisation of the disease, the description of its three pillars (parasite, mosquito and human host), its life cycle and our current understanding of what actually happens when you get malaria infection is very recent, starting in the early 20th century.

A tropical disease?

We’ve been surrounded by mosquitoes with a capacity for transmitting malaria for many centuries – and we still have those mosquitoes in Florida, in Barcelona, in Rome, in most places.

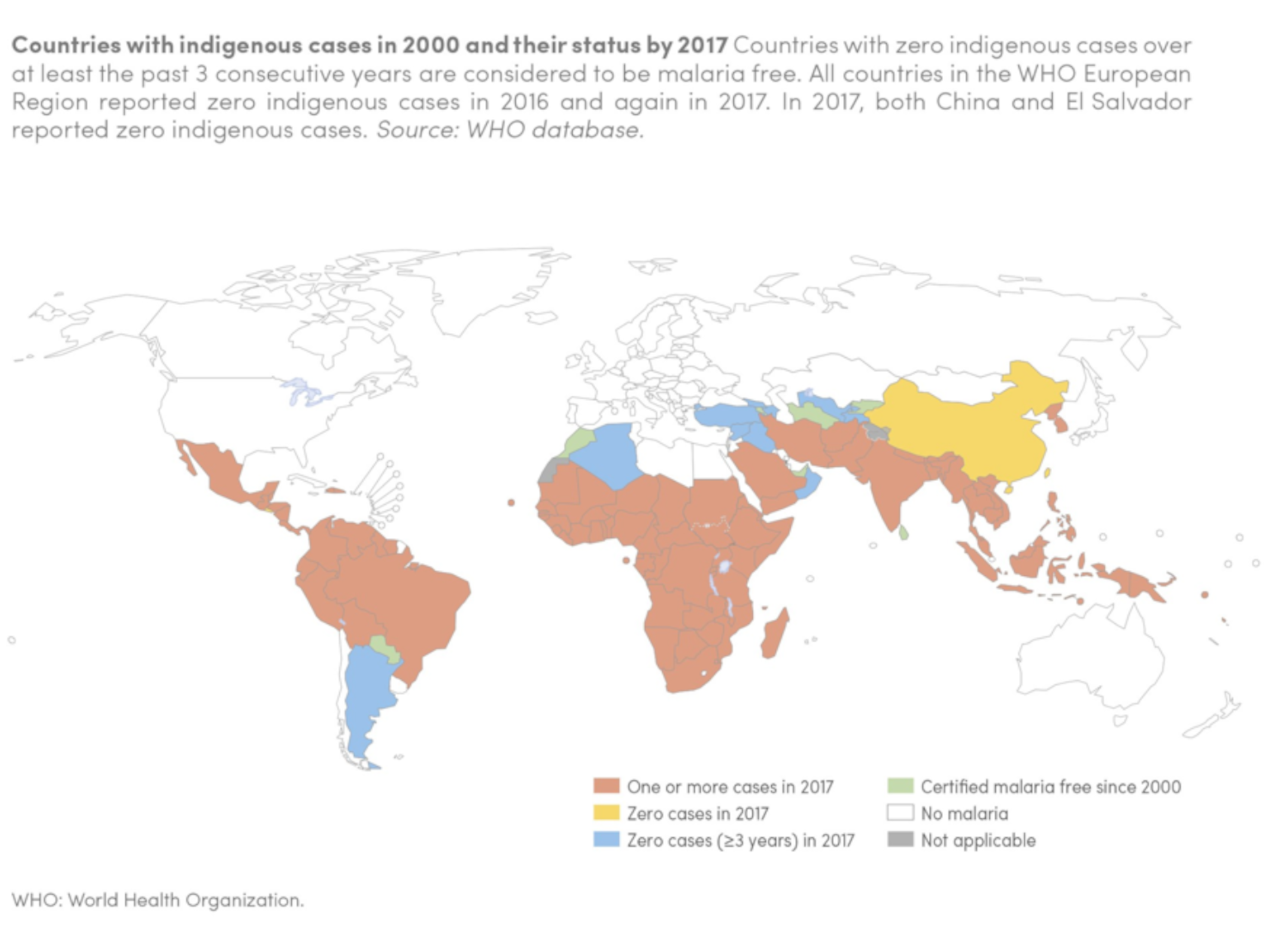

Around 100 years ago, we had malaria in most places of the world. The history of human development, with western countries becoming richer and dedicated efforts targeting this infection in those countries, was the critical path to eliminate malaria in the places where it was present before.

Countries actually managed to advance the fight against malaria by decimating these ponds, building around those areas which were full of marshes and eliminating stagnating waters. This dramatically reduced the number of mosquitoes that would circulate in this area and therefore reduced the risk of those mosquitoes transmitting malaria. So, if you had the right infrastructure, you could progress towards eliminating malaria.

Today, malaria is mainly transmitted around the tropics and that’s what has made people think that malaria is a typical tropical disease.

What 10 plus 1 equals

Malaria today is predominantly a problem of sub-Saharan Africa, even if significant transmission still occurs in Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, in the Pacific and in some places of the Americas.

Eleven countries constitute about seventy per cent of the entire burden of malaria in the world. Rather than saying 11, we now say 10 plus 1 because it’s 10 African countries plus India.

Discover more about

malaria, a global problem

Bassat, Q. (2020). Malaria, the invisible disease. EXP-Editions

Ashley, E. A., Pyae Phyo, A., & Woodrow, C. J. (2018). Malaria. Lancet (London, England), 391(10130), 1608–1621.

World malaria report 2019. (2019). WHO.