Thucydides wrote The History of the Peloponnesian War while the Peloponnesian War was still ongoing. The reason that he had the leisure to write such a massive and incredibly laborious work was that he had served as General during the Peloponnesian War, but after a tactical error, he was exiled from Athens. Thucydides says that his exile is precisely what afforded him the leisure to write, interview people, research and get to the bottom of what was happening during the war based on his conversations with people from both sides.

The History of the Peloponnesian War unfolds over eight books. The Peloponnesian War itself lasted from 431 BC until 404 BC. It ended with Athens’ defeat at the hands of Sparta and its alliance. The book cuts off in the year 411 BC, most likely because Thucydides died while he was still at work on the project. There are signs that he was at work till he died, constantly revising earlier parts that he had written. Nevertheless, he does not cover the years 411 BC to 404 BC of the war.

A timeless reference

The History of the Peloponnesian War became a timeless reference for politicians, military historians and scholars of international relations. This was precisely what Thucydides wanted it to be. He believed that he was going to be documenting events that truly reflect human nature in its unchanging manifestations over time.

He expressed the hope that people in future generations will learn from his work because human nature is not going to change all that much, no matter where you are or in what era you happen to live. Thucydides is really the first classical Greek author writing in prose who provides analyses of important events.

Herodotus, a historian who predated Thucydides and wrote about the Persian wars, is more episodic in the way that he tells history. He integrates more of mythology, folklore and what we might think of today as tall tales in fiction. Comparatively, Thucydides takes a much more clinical approach to narrating history. He analyses the course of the war in terms of forces, of competing movements and international relations. In the beginning of the book, Thucydides explores the causes of the war. He lays out the ideas in a way that provides us with models for thinking about other conflicts.

Influencing American foreign policy

The History of the Peloponnesian War has a unique tradition, particularly in the context of the American study of international relations and foreign policy. In Britain, France and Germany, Thucydides is still regarded as the father of history. In the United States, the influence of Thucydides’ work came with the Jewish emigres who had been forced to leave Germany and move to the United States. This was during and particularly right after World War II. They began working in political science departments in the United States. Having brought their classical education with them, they began confronting the kinds of foreign policy and national security questions that America was particularly invested in, and embroiled in at the time. One concrete way in which the History of the Peloponnesian War influenced American foreign policy had to do with the creation of NATO in the aftermath of World War II.

After the Persian wars, the Athenians found themselves at the head of what was at first called the Delian Alliance. This was an alliance of Greek states with Athens at the centre. The purpose of the alliance was to keep a major eastern power, namely the Persians, at bay. When NATO was formed, some generals were very self-conscious about the way in which NATO was reflecting what the Delian League had been. America now found itself in the Athenian position, at the head of a voluntary alliance, precisely with the purpose of keeping an eastern power, in this case the Soviet Union, at bay.

The Athenian thesis has become a famous way of describing the international relations principle that is embedded in the city’s history of the Peloponnesian War. The thesis was first named as such by the University of Chicago-based political philosopher Leo Strauss.

The gist of the thesis, as the Athenians explained in the context of international relations, is that wherever we have strong states and weaker states, the strong have the prerogative to act how they want. The strong do whatever they want; they do what they can, while the weak suffer what they must.

The Athenian thesis predates The History of the Peloponnesian War. It predates the war itself. The Athenian thesis even predates the Athenians, in a way, as illustrated by a story in a work by the early origins of Greek literature, titled The Works and Days by the poet Hesiod. In this epic of Greek antiquity, there is a dialogue between a hawk and a nightingale, in which the hawk has grabbed the nightingale in its talons and tells the nightingale, ‘I get to do what I want because I’m the big guy. I’m the tough one.’

The Athenian thesis develops over the course of The History of the Peloponnesian War as the Athenians constantly tell their allies that they have the prerogative to act in the way that they wish simply because they are the ones with the ships, the manpower and the money. The extraordinary thing is that over the course of the books, we see that the Athenians themselves become victims of their own success.

When the Athenians decide to invade Sicily, it is the Sicilians who are stronger, more diverse; who have greater manpower, greater resources and greater adaptability, which allows them to completely crush the Athenian forces and make them the victims, in the end, of their own thesis.

The Thucydides Trap

Many historians argue that Thucydides provided a blueprint for thinking about international relations. Graham Allison, political scientist at Harvard, has argued, that another thesis is embedded in The History of the Peloponnesian War. Allison explains that when you have a major superpower and another power on the rise, it is inevitable that the two of them will go to war.

Based on this thesis, Allison has made a prophecy that America is destined for war with China as China becomes a stronger superpower on the world stage. What I would argue, though, is that what Allison has called the Thucydides Trap is not so much a trap as it is the inevitability of how historical forces or international relations will play out. The trap is about the idea that as new situations keep arising, we keep getting sucked back into thinking along the lines of the ancient texts, thinking that there is no way out of them, that there is no room for creativity, no room for innovation, no room for the different texts from different traditions to give us a different perspective on how the international relations might play out or what we might best do.

Thucydides and his analysis of what happened between Athens and Sparta provides an interesting framework, one worthy of study. I do not think of it as necessarily a prophecy for the way that things must happen. We could be getting into a bit of trouble by constantly relying on these ancient texts to provide easy answers without us contributing the new analysis.

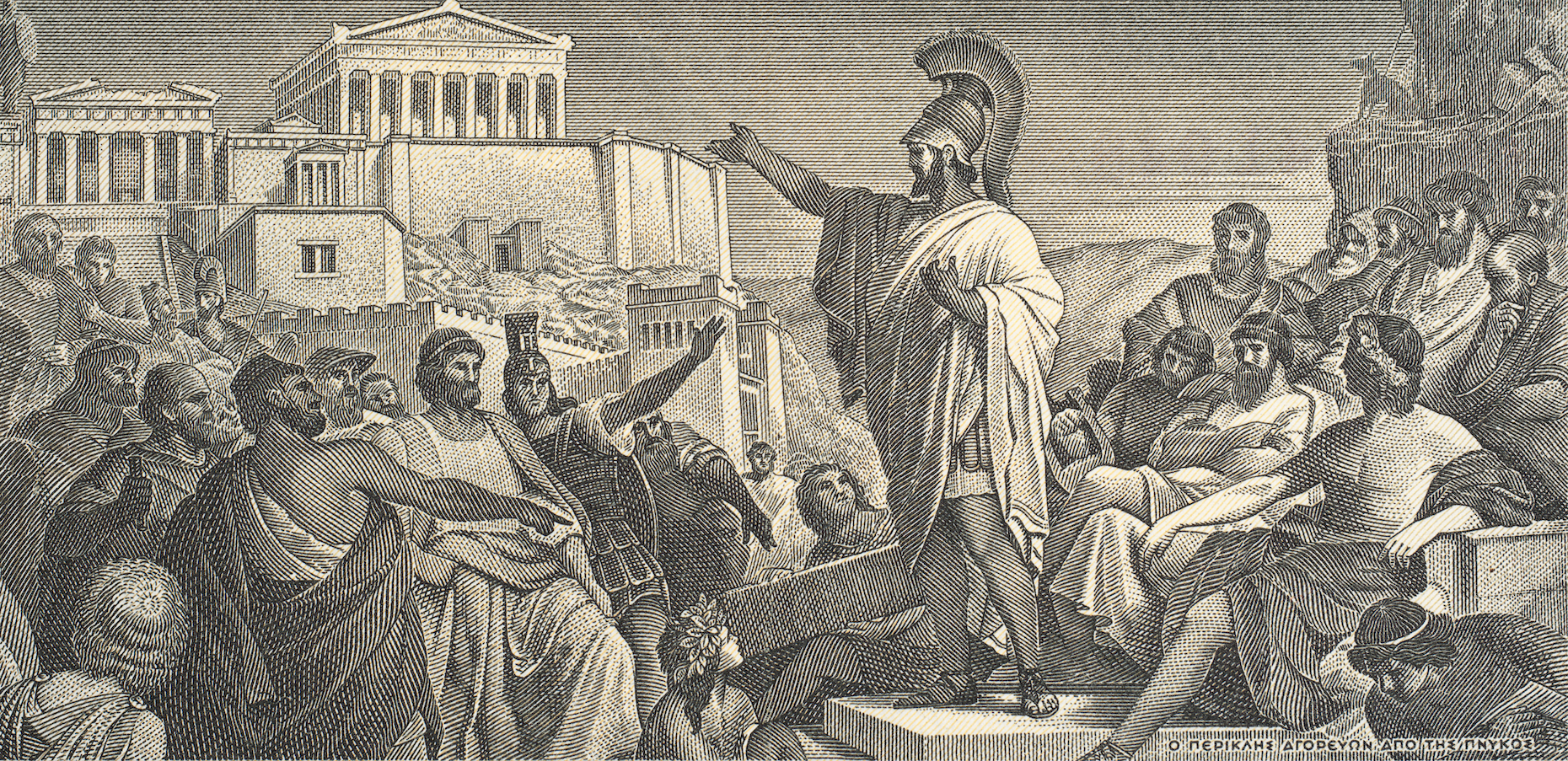

The most famous part of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War is Pericles’ Funeral Oration. This oration, which Pericles delivered at a public funeral for the dead who had fallen in the first year of the Peloponnesian War, has gone on to have this incredible, robust afterlife, particularly in the West, where people have seen it as a kind of blueprint of Western liberal democracy. That is one way in which it has been read. But people so often forget that soon after Pericles delivers his famous funeral oration in Book Two of The History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides goes on to narrate the consequences of an absolutely horrific plague that tore through Athens shortly after Pericles gave that speech.

That was a plague to which Pericles himself would succumb. Thucydides describes how the plague completely broke down societal structures. Earlier in the book, we get to read this account of a magnificent, highly choreographed state funeral for the war dead, in which every detail is taken care of, but when we move very shortly after that into the account of the plague, Thucydides comes right out and tells us that the normal burial customs were thrown out the window because there were simply too many bodies.

Thucydides is incredibly artful in giving us a speech where there is a triumphant declaration of the Athenian thesis, of Athenian exceptionalism, but Thucydides follows it up very shortly afterward with the passage, the narrative, that makes us view that earlier celebration of Athenian culture in a different light. It shows us that not all was quite as it seemed.

Greek and American imperialism

There are remarkable parallels between the American and the Athenian cases of imperialism. People have recognised this, and it is the reason that Thucydides has flourished in the American intellectual context. When it comes to the foreign policy and studies of British imperialism, Rome has made more sense as a comparand. The Romans were not shy about the fact that they had an empire. They were quite boastful of it. Both the Athenians and the Americans have, in a way, tried to hide their empire to cast their own imperialism in the guise of a project to spread particular values. It was made to seem as though their imperialism was a burden that has been shouldered somewhat unwillingly by the particular states.

The Athenians, in the aftermath of the Persian wars, acted as if they had to be at the centre of the alliance because it was then their responsibility to look after the rest of the Greek world. For this reason, the rest of the Greek world owed them their loyalty, their funding and respect for the role that Athens was assuming, as police and protectors of the Greek world. There is an interesting parallel between the course of modern American history and Athenian history. I think that as we go on, there is going to be more and more value in looking at how, in the aftermath of their defeat in the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians came to terms with the fact that they were no longer in charge of the Greek world, that they could no longer have a real claim to that exceptional position.

Justifying America’s invasions

Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War was often joked to be the Bible amongst American conservatives in the ’90s and early 2000s, when the United States was undertaking military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan. The example of the Athenian empire, as depicted in the Athenian values as espoused by Thucydides, really provided an impetus for a justification that intervention on the part of the United States was needed as a way of ‘looking after the weak’. If the US is in the position of the strong and, therefore, can do what it wants, it comes with the corollary that it should really be looking after the weak. The Athenian thesis in the ’90s and early 2000s came into play as a way of guiding the ethical justifications made for America’s invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan.