The pandemic has made us reflect much more on what is meaningful in our lives; what is important and what is less important. In the very first lockdown, many of us were extremely unfamiliar with even staying at home. In my own case, just by coincidence, I had had a very busy social and academic life before the lockdown. I had barely been home in the evening for weeks because I had been travelling, attending conferences and giving talks. Suddenly, I didn’t go out in the evenings for months. I went from a period in which I was very active, very busy, to more or less sitting in the same chair, looking at the same computer screen day in and day out. Of course, I’m not alone here. We are all in that same situation of having to make an adjustment.

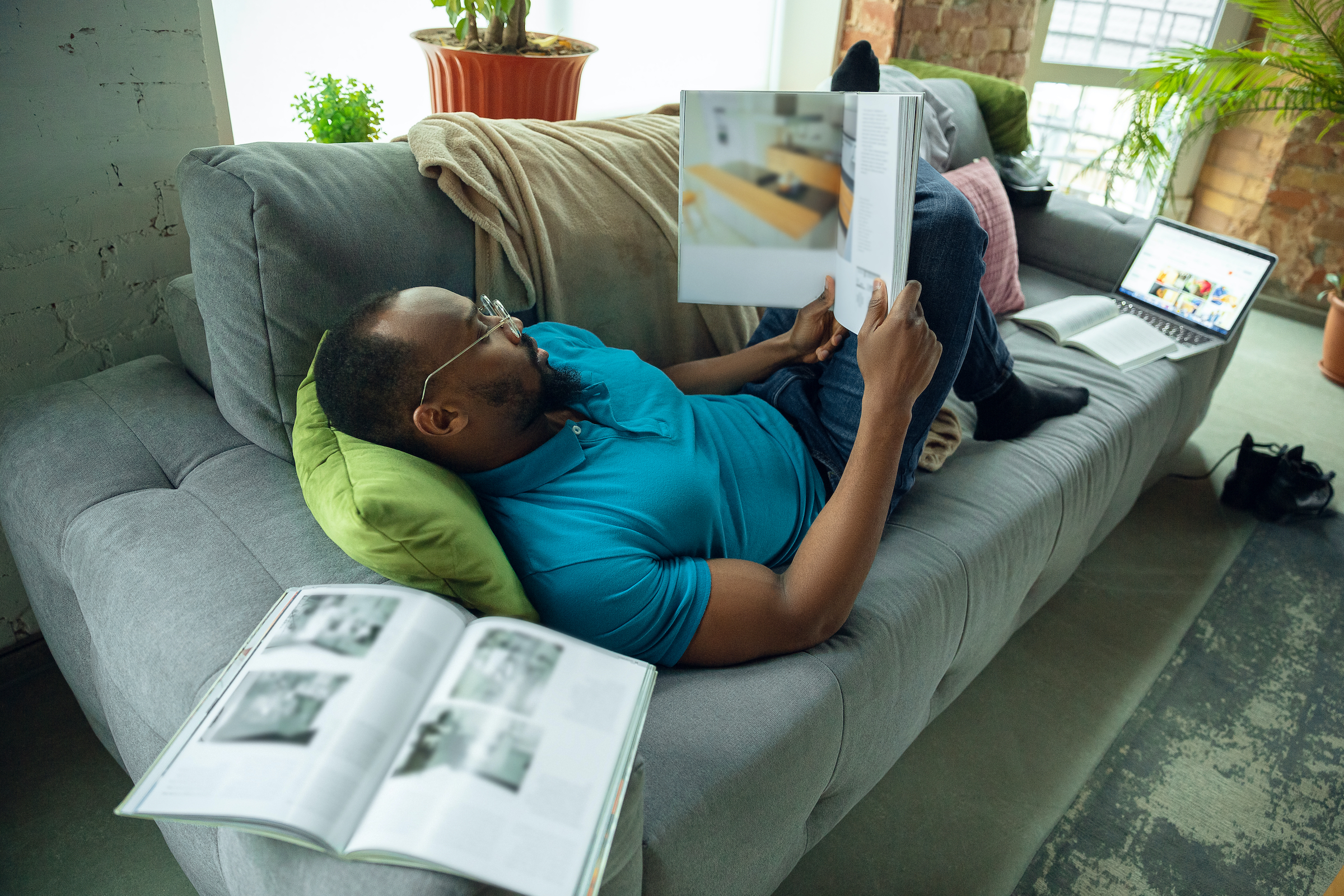

It is interesting to think of the different ways in which people have adjusted. Some people tried to live a life as close to the one they had before the lockdown. They would have dinner parties by Zoom, where you would have people cooking the same dinner in different kitchens and then trying to have a conversation. I don’t think that idea really caught on as a way of spending an evening together. And so, people have adjusted in different ways and have found value in doing different things. Books sold in record numbers. Jigsaw puzzles reported record sales. People are finding different ways of spending their time, and this is also getting us to reflect on what’s truly important and what’s not so important in our lives.