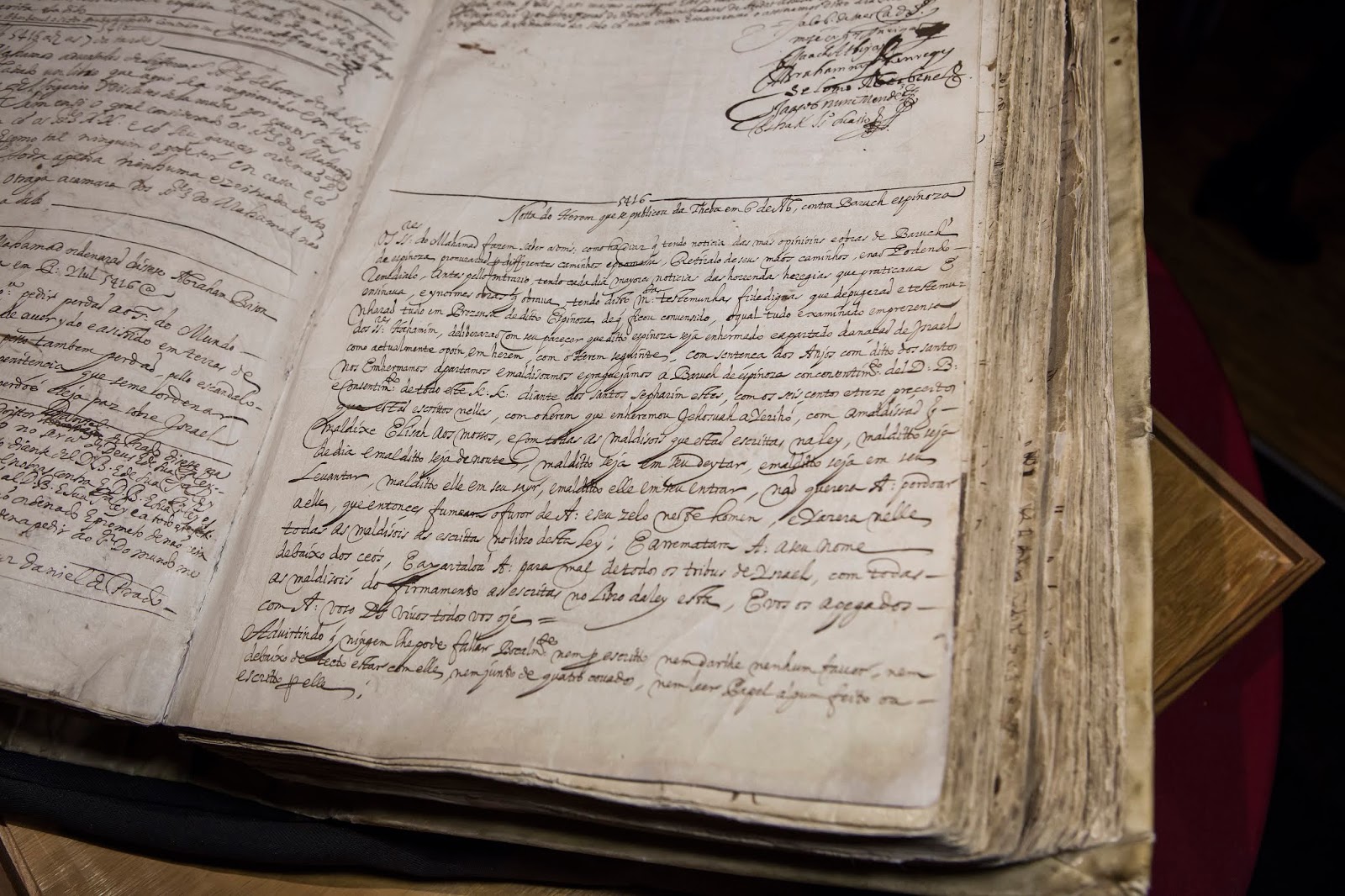

Although Spinoza lived in one of the most harmonious parts of Europe at the time, it was nevertheless, by our standards, politically fairly wild. He lived through the public lynching of one of the leaders of the Dutch Republic, de Witt, and his brother. He saw a number of his friends prosecuted for publishing work that offended Church and State. He was extremely familiar with internecine religious and political feuds and he himself complained of being unjustly branded an atheist and being made notorious because of it.

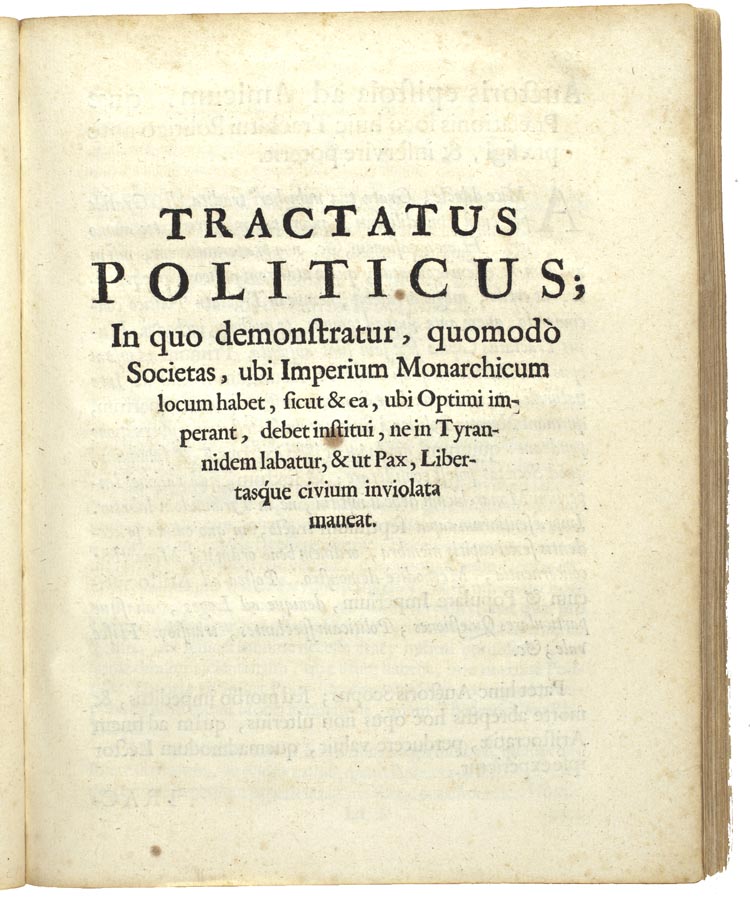

So, we see that Spinoza sets great store by this value of fortitude, this philosophical motivation and desire to live together in the light of your understanding and to use your understanding to build relationships with other people and to co-operate with them. One of the questions that Spinoza is particularly interested in is what sort of politics can do that. What sort of State do we need to help us live like that as effectively as possible?