This seems puzzling at first glance because, particularly in liberal reading of Christian ethics and theology, we think of Christ as a peacemaker and of Christians as pacifists. But American theologians and warriors have found many ways of squaring this circle. A concrete illustration is that one of the most famous firearms made in the US in the late 19th century was a rifle that was referred to as the “peacemaker” because it put the power to impose order, to execute vengeance and to inflict punishment into the hands of powerful white men. Another way this tension has been squared refers to passages of the Old Testament. You find the Israelites engaged in conflict with their enemies, and references to Yahweh as a God of War or the Lord of Hosts.

Inherent misunderstandings about religion and violence

Professor of Sociology and Religious Studies

- Contrary to popular belief, some of the worst crimes against humanity in the 20th century were committed by secular movements – while some of the fiercest opponents of these movements were religiously motivated.

- We can also see the idea of a kind of mythical past that will somehow be regenerated in a utopian future through cataclysmic violence in secular movements – like Nazism.

- One thing that many people find puzzling today is that violence committed by politically powerful religious majorities is treated very differently from violence committed by marginalised religious minorities.

Religion is not always behind acts of extreme violence

What exactly is the relationship between religion and violence? One view which is quite common today, is that there is something inherently violent about religion that has to be contained. If we look back at the history of the 20th century, a century of crimes against humanity and genocide, we quickly realise that some of the worst crimes were actually committed by secular movements and that some of the fiercest opponents of those movements were religiously motivated.

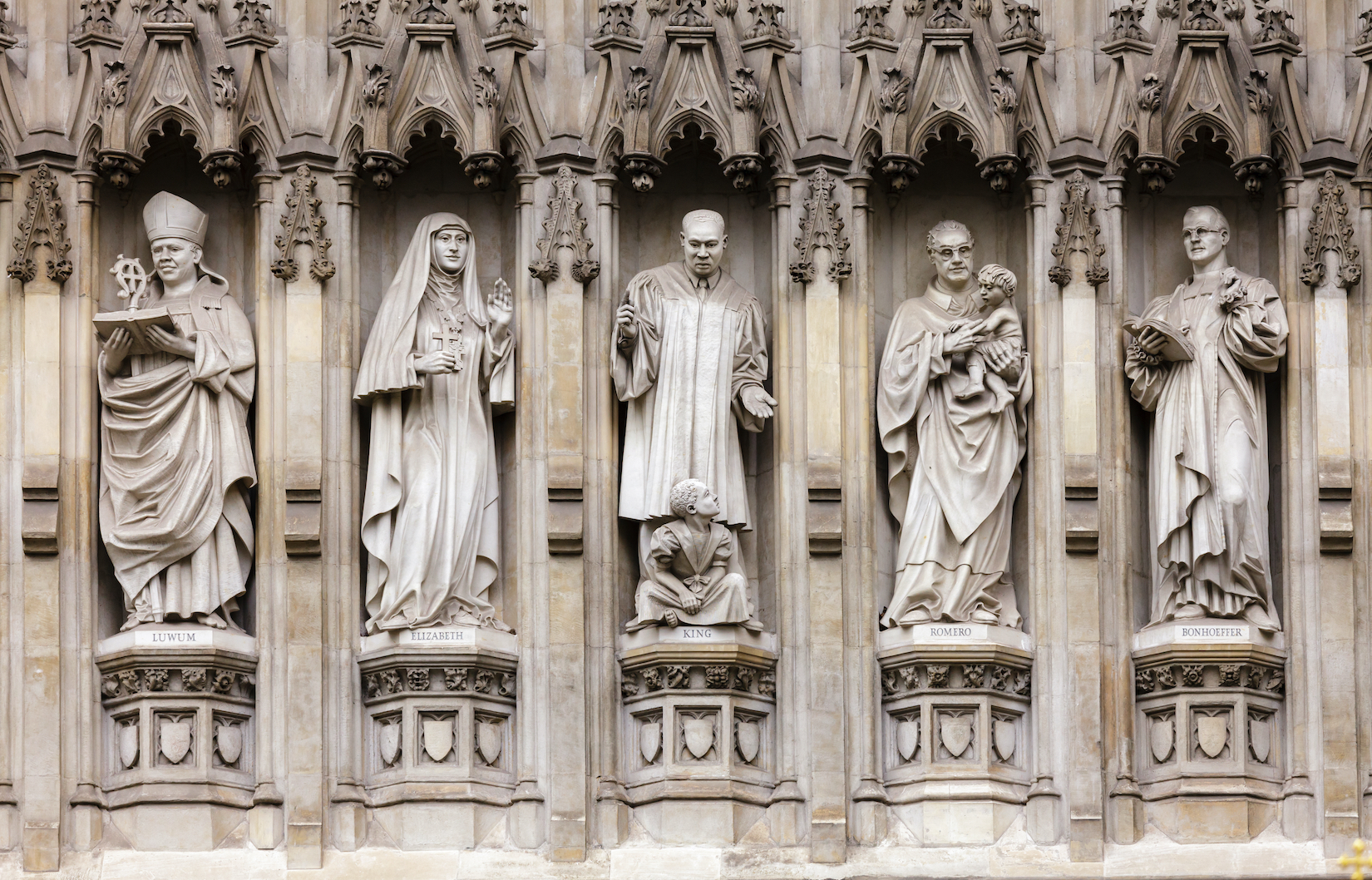

This becomes clear whether we’re talking about heroic individuals like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German clergyman who resisted Nazism, or talking about it on a collective level. For example, in the case of the solidarity movement in Poland, which was crucial to toppling Soviet rule and the Communist Party in Poland, instead of looking for something specific or distinctive about religious worldviews and religious movement, it makes more sense to think about what is common to religious and secular ideologies and movements that have led to extreme forms of violence. If we pose that question, a couple of things come fairly quickly into view. One is the sharp distinctions between “us” and “them” and a dehumanising way of talking about or representing the other.

Westminster Abbey façade detail with 20th century Christian martyrs Janani Luwum, Grand Duchess Elizabeth of Russia, Martin Luther King Jr, Oscar Romero and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. London, UK. By Dmitry Naumov.

“Us” and “them”

If we look at how this works in the case of religion, again, specifically in Judaism and Christianity, there are really two fundamental sources. One is an understanding of a particular group, nation or movement as somehow chosen – an analogy to the ancient Israelites – and not simply chosen, but also destined to act as an instrument or an army of God in the world and opposed to other peoples, other groups who are somehow inherently evil, eternally damned, somehow less than human, somehow not really themselves, also created in the image of God.

A second thing that I think is common to secular and religious movements, which tends to generate violence, is a mythical utopian understanding of the past or the future. It could be the idea that there is a golden past to which the group has to return. Or it could be the idea that there will be a last judgement of the final chapter in history; a cosmic battle between good and evil, in which violence in either case becomes a source of regeneration.

Secular regeneration through violence

We also see this otherness in the case of communist movements, that dehumanisation of the class enemy of the bourgeoisie; or, if we look at fascist movements, the dehumanisation of a racial or ethnic or religious other – most obviously in the case of the Shoah and Nazism and the role of antisemitism and the rise of Nazism. We can also see this idea of a mythical past that will somehow be regenerated in a utopian future through cataclysmic violence – in the case of Nazis, the idea of a golden Germanic or Teutonic past that will be regenerated through genocidal violence and imperial expansion, creating a sort of thousand-year renewal of the Empire.

This, in turn, is not radically different from very literalist understandings of apocalypticism within certain movements in Christianity – this idea of the last judgement of a tribulation, of a final sorting out of good and evil and the role that violence, sacrifice and warfare will play in bringing about this ultimate regeneration.

The rise of religious governments

When there is a collapse of political authority in instances of State breakdown, in periods of revolution or mass crisis, well-organised religious communities and their leaders can and sometimes do try to step into the breach. Recent examples include the efforts of the Muslim Brotherhood to take over Egypt in the wake of the collapse of the Arab Spring. Even more horrifically, we could talk about the rise of ISIS in the shadow zone created between Iraq, Syria and Iran in the wake of the war there, sparked by US intervention from the 1980s onwards. Religious communities have the institutional capacity to do many of the things that States do to impose law and order, to provide welfare and charity and so on.

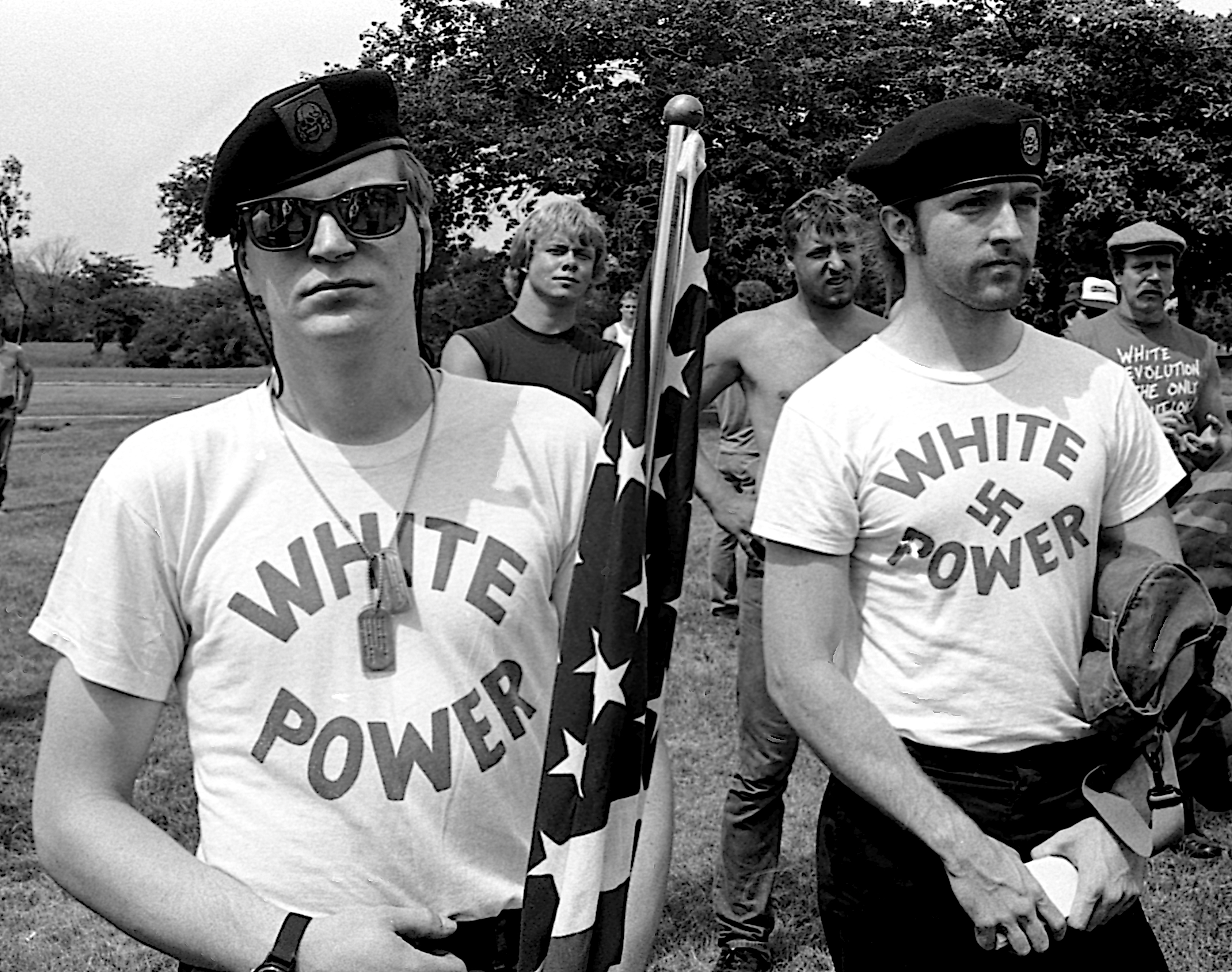

I think it’s important to draw a distinction between violent religious movements which succeed in capturing State authority and violent religious movements that do not. There’s a real difference, for example, between some of the violent white supremacists, militias that you find currently in the United States and ISIS, not necessarily in terms of their ambitions and ideology, but in their ability to commit mass acts of violence on a truly genocidal scale. There is an organisational component here that’s important to think about in addition to the ideological or theological component.

The ongoing association of religious violence and Islam

One thing that many people find puzzling today is that violence committed by politically powerful religious majorities is treated very differently from violence committed by marginalised religious minorities. There’s a very clear example of this in the United States over the last 20 years. If you contrast the response to the 9/11 attacks to the Capitol insurrection or to two other instances of white supremacist terror, such as occurred in Georgia, Florida, California or elsewhere, that violence committed by the majority, by the dominant religious group, is not treated as a threat to the social order by many people.

I don’t think that you can really understand that unless you think about the ways in which religious and national identity are connected with one another. In the United States, Muslims are inherently seen as outsiders, as threatening, as difficult to integrate and are therefore treated very differently to white domestic terrorists when they act in the name of Christianity.

The embedded warrior tradition in American culture

Many people watching recent events culminating in the Capitol insurrection, looking at the rise of radical neo-Nazi and white supremacist and identitarian groups and vigilante groups, see these “irregular groups” and think this is something new, something strange. What explains the emergence of these movements? In fact, if we take a longer view of American history, those kinds of groups are the rule rather than the exception. The exception is the long period beginning in World War I and especially following World War II, where most violence is organised in the form of a regular military and directed beyond the borders of the United States. But there is an incredibly long history of militia and vigilante violence and irregular tactics in the history of the United States. The revolution itself was basically fought as a form of guerrilla warfare against the regular tactics and uniformed military of the British crown.

There are more examples of this, with the Indian fighting up through the end of the frontier in the late 19th century; and in the vigilante violence which was part and parcel of the plantation system and the slave economy in the southern United States, where all able-bodied white men were required to participate in so-called “slave patrols”, which were not authorised by the federal government, or even by the State government, but typically organised by local powerful landowners. All men were also required to participate in the exercise of extrajudicial violence against runaway enslaved persons. So, there’s a really long history of this.

Where a Protestant ethic meets a warrior ethos

The Ku Klux Klan is as American as apple pie. Today, we often think of the Ku Klux Klan as simply a racist and white supremacist group. Of course, it was that, but it was also a specifically Protestant group, which was not only racist towards African Americans but towards Jews, towards Italian, Irish and other Catholic immigrants; violent towards any group that could threaten what it saw as the rightful inheritance of white Protestant Christian men and their God-given right to govern the United States, to govern racial and religious others. There is a very old intertwining.

Chicago, Illinois, 28th June, 1986: KKK members and a white supremacist group, the America First Committee, hold a rally in Marquette park. By mark reinstein.

A very old and often repeated scene

In the United States, there has always been a connection between a warrior spirit and the Protestant ethic, in particular. In that sense, there’s what we saw in the interaction at the Capitol – a bunch of gun-toting, mostly white men trying to seize control of the government, a government which they believed to be illegitimately controlled by a collection of individuals that included too many people who were neither men nor white nor Christian. This is a very old and often repeated scene in American history.

Discover more about

religion and violence in the US and beyond

Gorski, P. (2017). American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present. Princeton University Press.

Gorski, P. S., Kyuman Kim, D., Torpey, J., et al. (2012). (Eds.). The Post-Secular in Question: Religion in Contemporary Society. NYU Press.

Perry, S. (forthcoming). Flag and Cross: White Christian Nationalism and the Threat to American Democracy. Oxford University Press.