Lacan and the human mind

Psychoanalyst and Professor of Psychoanalytic Psychology

- For Lacan, a psychoanalyst should create a space in which a patient can speak their mind without the analyst imposing meaning.

- Lacan’s variable-length sessions often lasted only five or ten minutes, and patients didn’t know how long a session would be.

- Lacan’s concept of “object a” reflects the notion that every object of desire contains within itself the source of dissatisfaction.

- Lacan became known for his weekly seminars, which drew large audiences interested in his ideas on the human mind.

Creating space to speak

Jacques Lacan was a clinician throughout his life. Until almost his last days, he was involved with patients. So however abstract his theory may be, it is rooted in clinical psychoanalytic experience. Occasionally he was also a psychiatrist, and occasionally he acted as a medical doctor. He was intermittently consulted by Pablo Picasso, for example, not for psychoanalytic treatment but for medical treatment. However, throughout his life, roughly from the late 1930s until 1981, Lacan was a clinician.

For Lacan, working clinically as a psychoanalyst means that you create a space in which a patient is being given the opportunity to speak their mind without the analyst imposing any preconceived meaning upon that discourse. One of Lacan’s very famous phrases was gardez-vous de comprendre, which in English means something like ‘stop yourself from understanding’. So he sent out a message to other psychoanalysts that they should always guard themselves against understanding too quickly what the patient was trying to convey.

Space for creativity

That means that the clinical space also becomes a creative space. It becomes an environment in which speech is being given the freedom to move into all kinds of different unknown directions without the psychoanalyst steering it into a particular direction, or at least without the psychoanalyst pinpointing a particular meaning as the repressed, unconscious cause of the patient’s conflicts.

Lacan actually took it a step further by arguing that the ultimate goal of the psychoanalytic treatment should not be to find the one and only repressed meaning responsible for the patient’s conflicts and symptoms, but that it would actually be almost the other way around. The ultimate goal of psychoanalysis would be about bringing meanings in relation with other meanings, so that the mind could again become used to a state of semantic flux, and the patient would again acquire the mental agility or versatility to find their way between the complexity of meanings that we have to negotiate on a daily basis.

Sessions with Lacan

People over the years have told all kinds of stories about their analyses with Lacan. I’m not sure there is one single template or paradigm that you can apply to a Lacanian session, which, of course, would make total sense from the perspective that what matters is the unique lived experience of every single patient.

However – and this is one of the most controversial aspects of Lacan’s entire contribution to psychoanalysis – what characterised Lacan’s practice was the technique of the variable-length session. It is because of this technique that he was eventually banned from training in his own group and eventually expelled from the International Psychoanalytical Association. So what characterises a Lacanian psychoanalytic session is that the patient never knows in advance how long that session is going to last. During the 1970s, it wasn’t unusual for Lacan to operate with five- or ten-minute sessions.

Plaque affixed to n ° 5 rue de Lille, Paris 7th, where Jacques Lacan (1901-1981) had his psychoanalysis office from 1941 until his death. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The variable-length session

Lacan introduced this principle of the variable-length session because he was looking for a type of interpretation that would circumvent the new meanings that would be inevitably attached to any standard Freudian interpretation. In other words, in the variable-length session, a psychoanalyst – Lacan in this case – would say nothing but ‘We shall stop there for today’ or ‘I shall see you tomorrow.’ The rationale for that principle was that it would constitute an interpretation, a punctuation of the patient’s words that would not contain in itself a meaning that would be alienating, that would potentially estrange the patient from his or her own experiential word.

Of course, when you practice that technique, you never have the reassurance that the patient will actually take it and come back the next day. Let’s not forget that Lacan was a very expensive psychoanalyst. So you could end up paying a significant amount of money for a five- or ten-minute session. What guarantee did he have that patients would come back? Sometimes they wouldn’t come back, but a lot of the time they did. Why did they come back? There is no doubt in my mind that they often came back because it was Lacan – because they had already built a so-called transference, a so-called attribution of mastery knowledge to their analyst that actually prevented them from leaving him on the spot.

A wide range of patients

Because Lacan trained as a clinical psychiatrist, he learned the ropes in psychiatric institutions and therefore primarily worked initially with psychotic patients. When he later opened his own clinical practice as a psychoanalyst, it wasn’t just the psychotic patient who came to see him. Yes, on occasion, people who had had psychotic breakdowns still came to see him or were sent to him. The most famous example is probably Dora Maar, who, after she had had a spat with Picasso, had a bit of a psychotic breakdown and was sent to Lacan for treatment. However, when he practised as a psychoanalyst, he didn’t just work with psychotic patients. So many patients – and we have their written accounts – went to see him because of what you could call problems in living or a general feeling of malaise.

Portrait of Dora Maar. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Lacan’s “object a”

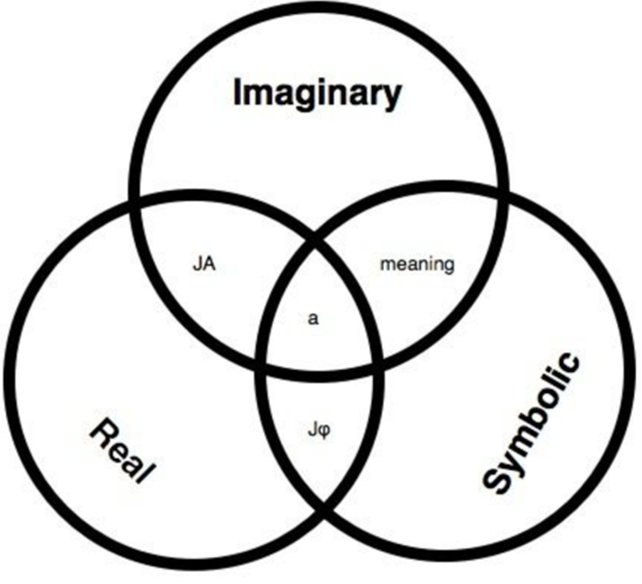

One of the symbols that permeates a large swathe of Lacan’s work is the famous object a, which regularly only occurs as the letter “a” italicised. In a seminar during the mid-1970s, Lacan said that there was only one thing he had invented, one thing he had contributed to psychoanalysis, and it was the concept of the object a.

This object a is not easy to understand, but effectively what Lacan had in mind was: the object to which a desire consciously or unconsciously is attached is never intrinsically satisfying. Each and every object of desire contains within itself the source of dissatisfaction.

Lacan used the notion object a or the letter “a” in the same way that you would use the “a” as an alpha privativum, as we call it in linguistics, in words such as “asexual” or “apolitical”. In words such as those, the “a” stands for an absence, for a negativity, for a “non”. So Lacan’s object a is designed to capture the point at which each object of desire contains within itself a negativity, a point at which it is not fully satisfactory.

You think you desire the object, but actually what you desire is not the object; it’s only ever a fantasy of the object. Because it’s only ever a fantasy of the object, the object, when it finally appears, can only ever be dissatisfying, as a result of which it acquires this dimension of an object a – and desire, of course, shifts towards something else. So the object a, in other words, is also the “a” object. It’s the non-object. It’s the negative object. It’s the object that fails to satisfy, to quench the desire that is attached to it.

The Alien Jouissance Borromean Knot - Lacanian Psychoanalysis. Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Lacan’s famous seminar

During the 1950s and later on, Lacan was primarily known for his seminar, and this seminar was essentially a weekly lecture course in which Lacan largely improvised his own ideas around various theoretical and clinical topics in psychoanalysis. It is by virtue of this seminar that Lacan, from the 1960s onwards, really gained notoriety and that his name started to spread.

What was initially a relatively small group of people – in 1953, it was probably a group of about 30 people – eventually in the 1970s became an auditorium of 800 people. Needless to say, those 800 people were not all people who were training to be psychoanalysts. They were people who were just coming to Paris to see and to hear Lacan speak about one or another aspect of psychoanalysis, which at that point was actually also one or another aspect of his own innovative revolutionary theory of subjectivity and the human mind. So Lacan’s seminar became a spectacle, as a result of which you had to stand in line. You had to queue; you had to arrive two hours in advance in order to ensure that you had a good seat to see and hear the master when he finally arrived.

Discover more about

Lacan, the practitioner

Nobus, D., & Downing, P. L. (Eds.). (2006). Perversion: Psychoanalytic Perspectives/Perspectives on Psychoanalysis. Routledge.

Nobus, D. (2000). Jacques Lacan and the Freudian Practice of Psychoanalysis. Routledge.