There are many models for making higher education affordable for middle-class and lower-income families. The first place I would look is actually from within the history of the United States. I have my degree from UC Berkeley. The UC schools were once free or very low cost. That was at a time when higher education could vault people from lower-income backgrounds into the middle class and beyond. Californians knew that the system was there to serve them.

Renewing democracy by restoring free tuition

Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis

- The general trend since the 1970s has been for governments to withdraw from supporting higher education, putting more financial pressure on middle-class families.

- Free tuition is essential. Democracy is improved when young people from different backgrounds come together and learn how to work through their differences.

- Current US politicians, from the president to state legislators, are more responsive to the idea of higher education reform and debt cancellation than they have been in decades.

Social speculation

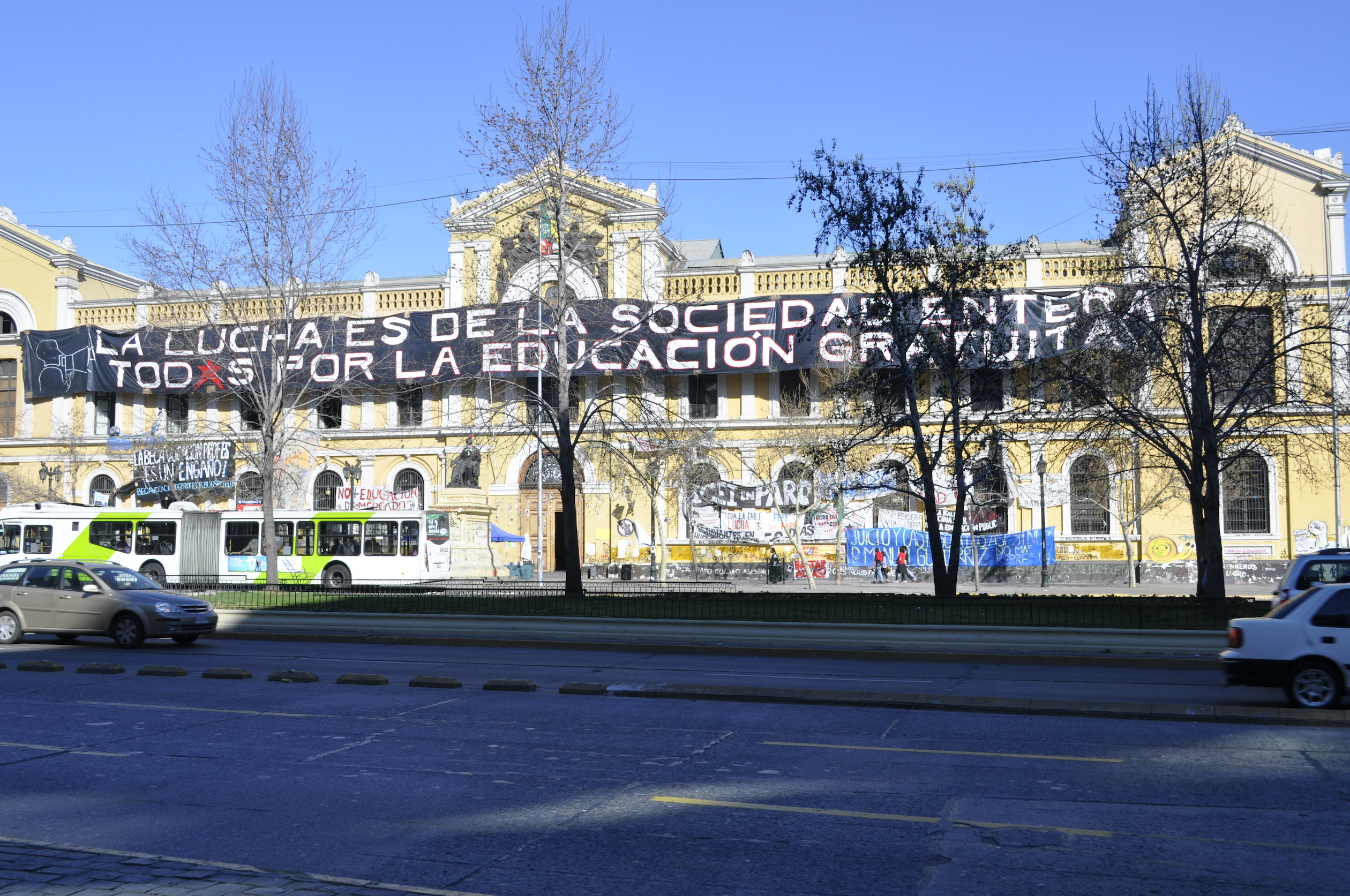

The financialisation of higher education that we see in the United States has its equivalents around the world. The UK and Chile are just two examples of places that are now relying more on students and their families to pay high sums for education.

One of the consequences of the financialisation of higher education is that families are forced into a speculative position. College is more important than ever for young adults to have a shot at a good life, well-paid work and family stability – not to mention good health and longevity. Students and families have to put down an enormous amount of money simply to give themselves a chance, but they have no way of knowing whether it will pay off.

That is what I call social speculation. They’re putting down money now, taking on debt and making investments for an idea about the future that may or may not come to pass.

The withdrawal of government from higher education

There are certainly commonalities between the US, Chile and other countries around the world. One is that the increased cost of higher education is part of the government withdrawal from supporting the essentials of middle-class life, putting more and more pressure on families.

Of course, this doesn’t always go one way. In Chile, for instance, activists have put pressure on the government over the past few years to expand access to higher education for at least part of the population. But the overall trend since the 1970s has been for governments to privilege private, high-cost education.

Photo by gonzagon.

A range of positive effects

Borrowing an approach from feminist economics, we should look outside of the formal domain of higher education for its effects. It is not only that higher education has the potential to raise the income of graduates. It is also part of the aspirations of a family across generations, which then is realised through the higher education of young adults. We need to be thinking not only of narrow economic effects but of broader effects on the family and the household.

We should also be thinking about how the household has put into higher education. That is something that we don’t normally recognise in the narrower economic view of what higher education is for, but it is essential when analysing the aspirations of young people.

Why free tuition matters

Free tuition is essential. One of the common objections to that idea is that if we support free tuition for state institutions, we will be supporting the children of wealthy people, too. This is, again, a much too narrow perspective on higher education predicated on the idea that the system should pay for itself.

We need to think more broadly. First, higher education is a place where young adults should be coming together across classes. Lower-income students, middle-income students and wealthy students should all be able to mix at our higher education institutions. That also means that we should be taxing wealthier families to pay for these institutions. It’s not about supporting wealthy students. It’s about supporting our democratic system so that young people can learn how to work together across differences to lead us into a better future.

Photo by Rawpixel.com.

Renewing our democracy

We need to be thinking about colleges and universities as places where young people come together to gain the tools and the capabilities to make our democracy new. We have problems around the world and especially here in the United States with our organs of democracy falling apart. We need to have places where young people learn to work together, whether it’s in classrooms or campus clubs. These are spaces where students can practise democracy, and we need to be investing in those spaces.

The financialisation of higher education has tied us to the inequities of the past. The right to the future demands a kind of break from the fundamental harms that we’ve done so that we can reinvent where we need to go. Young people need to be able to distinguish themselves from the damage that we’ve brought to them, to move us all forward. Carrying large sums of debt for their higher education only ties them to the past.

Collective solutions

I think we’re in a very important moment where collective solutions are finally possible again. Of course, we have a very strong push for individualism on the one hand, but now, especially in this moment of the pandemic and hopefully moving forward, that idea that we are all part of one another’s lives, that we are inextricably tied, is absolutely on the agenda again.

I hope that higher education will be, too. In fact, we’re already seeing movement in terms of collective higher education solutions. For example, President Biden is discussing the idea of student debt cancellation with influential members of Congress. The idea that we have put too much of a burden on our young people for their education is very much on the table. There is also a movement at the state level to make higher education free or low cost for middle- and lower-income families. In states like New York, New Mexico and Michigan, politicians are being responsive to collective solutions in ways that they haven’t been in decades. This is all due to the pressure that activists have put on state legislatures and representatives, senators and the president, to drive these collective actions forward.

Photo by Ben Von Klemperer.

A turning of the tide?

A notion arose in the 1990s that a college degree was primarily a benefit to the person who held it. In other words, that education was a private good. It was that fundamental idea that led to the expansion of loans in the United States and to policies around the world that compelled students and their families to pay for higher education.

Today, I think we’re seeing that idea being reversed. We’re starting to appreciate again how higher education is, in fact, a public good. It is something that we all benefit from. When teachers, nurses or doctors are educated, they support us all. We need people to be educated to serve their communities and their countries, and to move us forward.

Discover more about

the future of higher education

Zaloom, C. (2018). A Right to the Future: Student Debt and the Politics of Crisis. Cultural Anthropology, 33(4).

Zaloom, C. (2019). Indebted: How Families Make College Work at Any Cost. Princeton University Press.

Zaloom, C. (2018). How will we pay? Projective fictions and regimes of foresight in US college finance. Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 8(1–2).