This is very important in terms of explaining why people accept oppression and subordination, because they believe that somehow these outside forces are what determines human history. So part of what Marx contributes, and still contributes today, is the idea that mankind itself has produced these circumstances and, in turn, can reverse those circumstances if it wishes.

Why Marx still matters today

Professor of the History of Ideas

- Some of Marx’s lasting ideas are that human creativity transforms the natural world, that mankind has produced its economic circumstances and can therefore reverse them, and that revolution is a process rather than an event.

- Many of Marx’s insights go beyond the narrow definitions commonly ascribed to Marxism.

- A rediscovery of the concept of the dignity of labour could help us address today’s rising inequality.

The energy of capitalism

I would stress three points of Karl Marx’s continuing importance. The first is the picture he gives of the energy of capitalism, particularly in the first section of The Communist Manifesto, but also in Capital. It’s arguing that, through what he calls the forces of production, human creativity has actually transformed the natural world, and the historical world as well. In this sense, it’s the history of capitalism which matters most as one of the innovatory images which he establishes. This remains as valid today as it did when he was writing it in 1848.

The power of mankind to reverse its circumstances

The second point may be less familiar, which is that Marx started from a critique of the Christian religion. He was part of that generation which, having read Hegel, uses Hegelian criticism as a way of deconstructing what Christianity is about. There’s the work of David Friedrich Strauss, who argues that we shouldn’t be looking at Jesus as an individual but rather as the human race, and the development of the human race is the valid part of what Christianity is about. Secondly, of course, is the idea of Ludwig Feuerbach, in which man invents God, but invents a God who supposedly had created man.

This inversion is something which Marx also applies to the economy, in which mankind presents itself as being the victim of economic circumstances when, in fact, it has created those circumstances. Marx also talks about this idea of inversion in Capital, in what he calls the fetishism of commodities. Earlier on, he talked about it as a form of alienation, but the point is that it turns matters upside down.

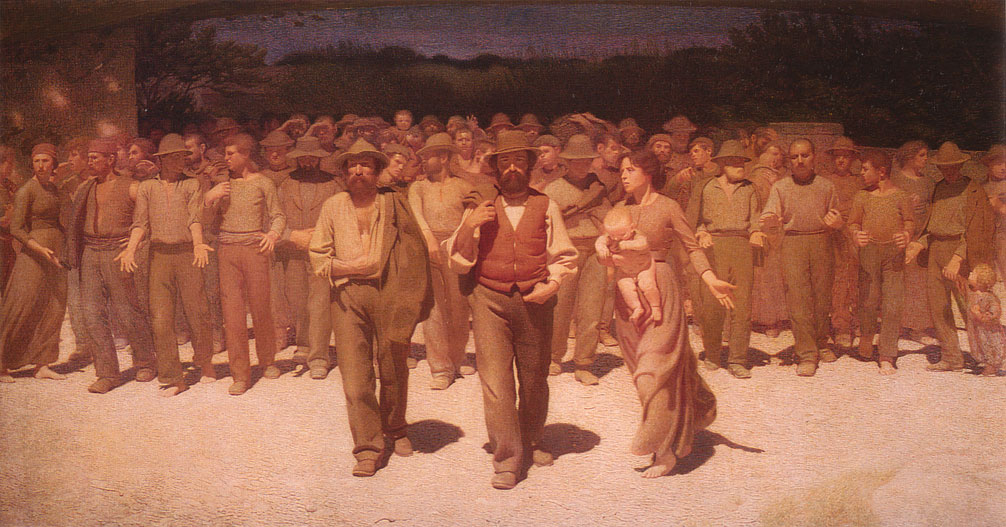

Class struggle by Giuseppe Pellizza. Wkimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Seeing the transition to socialism as a process

The third point worth mentioning is the way in which Marx’s thinking didn’t remain unchanged. He developed his theory from the 1840s to the 1860s, and he shifts the emphasis. In the 1840s, it’s really the abolition of private property itself. In the 1860s, it’s really encouraging a transition from capitalism through to what he calls the association of producers. That’s to say, it’s a process. It’s not – as people thought about the French Revolution, about the Jacobins, about 1848 – the revolution being a grand event. Of course, that happened again in 1917, and that’s why Marxism latches very much onto this particular idea of revolution.

But in the 1860s, Marx himself comes to think of the development from capitalism to socialism as being like what he has been writing about in Capital, about the development of capitalism from feudalism. In other words, it’s a process which is multifaceted and takes some time. That’s really one of the first statements about what a social democratic theory could be. And that remains, again, as valid an insight now as it was then.

The concept of the working class

There are various reasons why the working class came to be thought of as the prime instance of social transformation from the 1820s onwards. Since then, there has been a huge transformation in which the simple contrast between workers and capitalists is no longer simple at all.

Photo by Steve Sanchez Photos.

Workers themselves are not necessarily to be thought of as a single force today. They don’t define themselves very often as workers anymore. Indeed, given their political rights, they’re not in the subordinate or excluded position which they were in during the 19th century. For that reason, I don’t think one should automatically think of a revolution made by workers.

It’s also true that developments are different in the Third World, as we used to call it, compared to the advanced countries. There are still situations in which the producers are the people who would have the opportunity or at least who would be needed if a real social transformation were to take place. But generally, the focus on the working class no longer adequately describes the situation to be made if social transformation is needed.

Understanding Marx beyond Marxism

It is important to try to understand Marx outside the framework which was established by the development of Marxism in the late 19th and 20th centuries. It takes a considerable amount of intellectual effort in order to see that various of his insights don’t have to be regimented into their respective positions as in Marxism. That means looking at Marx through fresh eyes, looking at man’s ability to transform both himself and the situation in which he lives as being the starting point, rather than this idea of social determination, which is the predominant association with Marx. Of course, the task is now simpler because most communist parties have collapsed or disappeared. However, in places like China, for example, these thoughts would still be very useful.

In terms of Marx’s writing, there’s an early fragment which remains important, called Theses on Feuerbach; that clearly says that the weakness of the socialist movement at the time was its overdependence on the materialist theory. Another important text is the evocation of energy in the first part of The Communist Manifesto. Of course, it’s worth revisiting Capital, in particular the last section which is about the development of primitive accumulation, which becomes a classic way of doing an economic history from feudalism to capitalism. There is also the idea of the fetishism of commodities, which points to this problem of inversion in human social structures and how that inhibits progressive change.

Addressing inequality today

The development of neoliberalism has led to the ever-increasing marginalisation of collective institutions, like trade unions or cooperatives and so on, and the development of an ever-more crude, possessive individualism, which is meant to account for human behaviour. What is needed is the rediscovery of some of the points produced by not only Marx but the labour movement around him, and that is the idea of the dignity of labour in itself. We’re not just consumers. We’re people who produce things. We do things. We should be accorded recognition and dignity in accordance with that.

Photo by John Gomez. NHS (National Health Service) workers march in protest from St. Thomas' Hospital to Downing Street, Central London, demanding a pay rise from Boris Johnson's Government.

One local example at the moment is the caring professions, the workers in the National Health Service and so on. There’s a need for a social theory that puts caring and the meaning of dignified labour at the top of our priorities, and that attempts to get rid of the sort of conditions I once studied in a 19th century context as casual labour, but is now called the gig economy.

The gig economy gets rid of mutual obligations between workers and employers and replaces them by these individualist and heavily disadvantageous arrangements, which does produce something akin to what socialists throughout the 19th and early 20th century predicted, which was a polarisation between an ever-smaller and richer ruling, possessing class and an ever-larger class who are without serious possessions.

If Marx saw the situation at the moment, he would be pretty depressed. But what he would also think is that, given his theory of history, things will change. Things develop despite themselves and open up opportunities which have previously not been seen. There would be little in the present situation to cheer him up, but his theory of history would, I think, give him some confidence about the future.

Discover more about

Marx’s continuing influence

Stedman Jones, G. (2016). Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion. Harvard University Press.

Stedman Jones, G. (2004). Introduction. In F. Engels, & K. Marx, The Communist Manifesto. Penguin Books.

Katznelson, I., & Stedman Jones, G. (Eds.). (2010). Religion and the Political Imagination. Cambridge University Press.