As a result, it is difficult to separate capitalism from the rest. It is difficult to figure out in what way capitalism manipulates emotions: how some emotions are not manipulated, and some are. The influence of capitalism is on culture, on values, on how we conduct our everyday life. But that’s not all. It also deeply influences our private life, even our intimate life, and the ways in which we speak to ourselves.

How capitalism has transformed relationships and emotional life

Professor of Sociology

- Capitalism defines our entire society.

- The 20th century concept of dating moved romance from the private to the public sphere, connecting it with the consumption of leisure.

- There has been a rise in “emodities”: commodities designed to provide emotions.

- It is difficult, if not impossible, to disentangle capitalism from emotional life.

Does capitalism manipulate emotions?

Capitalism manipulates and instrumentalises emotions, but exactly how is a more complicated question. Let me go back to the question of what capitalism is. Capitalism is no longer only an economy. It used to be, but it is now a culture. Some scholars even argue that it has become the whole of society. It covers almost the entire spectrum of our activity. Capitalism defines our entire society.

My work has focused on showing the ways in which the cultural grammar of capitalism has penetrated and reshaped the grammar of intimacy and personal relationships.

Capitalism is defined as an economy which puts the maximisation of profit at the centre of all economic activity, and even social activity; the maximisation of profit becomes an end in itself. This is why capitalism tends to view everything – from the state, its organisations and institutions to simple ordinary workers – as mere instruments and tools to maximise profit. This is bound to have profound consequences on society, on relationships and on our commitment to society.

Photo by AdaCo

How capitalism shapes romance

First, let me explain the ways in which capitalism has shaped and transformed intimate relationships. Let me take an example: romantic love. In traditional societies, romantic love was typically mediated or expressed through poetry, songs, music and rituals: what we call courtship rituals. The beginning of the 20th century, with the rise of consumer capitalism, is when we start producing mass goods, when leisure industries such as cinema and photography start spreading images, and when advertising starts becoming the cultural arm of capitalism.

Around this period, we observe a profound change in the meaning of what we call romantic love and romance. This change is manifest in the emergence of a new concept: dating. Dating means encountering someone for a romantic or sexual purpose, but it also means consuming some activity of leisure together, such as going to a restaurant, going to drink something, going to a dance hall, or using the car, as was often the case at the beginning of the 20th century. This had significant consequences on the feeling and the practice of romance as it took romance out of the domestic home and brought it out to the public sphere of leisure. It attached the consumption of leisure to the meaning of what qualifies as a romantic moment.

Tourism as a commodity of romance

This is the emergence of a new way of experiencing romantic relationships according to their capacity to stick to some kind of code that conforms to the codes that were offered by consumer culture. For example, think of a walk on the beach. A walk on the beach or a vacation in an exotic place are typically viewed as romantic moments. They have become so because they have been tightly associated with a consumer good emerging at the end of the 19th century and taking off after World War II which would become one of the most important industries: tourism.

Tourism is both an intangible commodity and a tangible one. That commodity becomes associated with romance. For modern people, having a romantic experience is often associated with the experience of tourism, of having dinner in a faraway place. We have seen, for example, the emergence of a large industry of honeymoons combining tourism with romance. That’s one example of the ways in which capitalism takes over a domain of private life, of emotional life, and transforms it – but in a way that feels very much our own. We never really feel the intrusion of the public world of commodities when we have these experiences. On the contrary, we have a heightened experience of the bond that connects us to someone else.

Photo by Maridav

Emodities: emotions as commodities

A second example of the ways in which capitalism transforms and connects to our emotional life is the notion of “emodities” – emotions and commodities – a new category of commodity that is not only experiential but, more specifically, emotional. One of the greatest characteristics of the development of capitalism throughout the 20th century is the development of experiential commodities. An experiential commodity is a commodity that resides in the experience you have of it. For example, going to Disney World: that’s an experience. But some commodities are actually about providing certain types of emotions.

Think of a workshop to modify your high level of anger, or to have better emotional communication with your husband. We think of these as psychological services – and these are indeed forms of psychological services – but we can also think of them as being emotional commodities, because what you’re actually purchasing is a particular emotion. It is a particular emotional transformation.

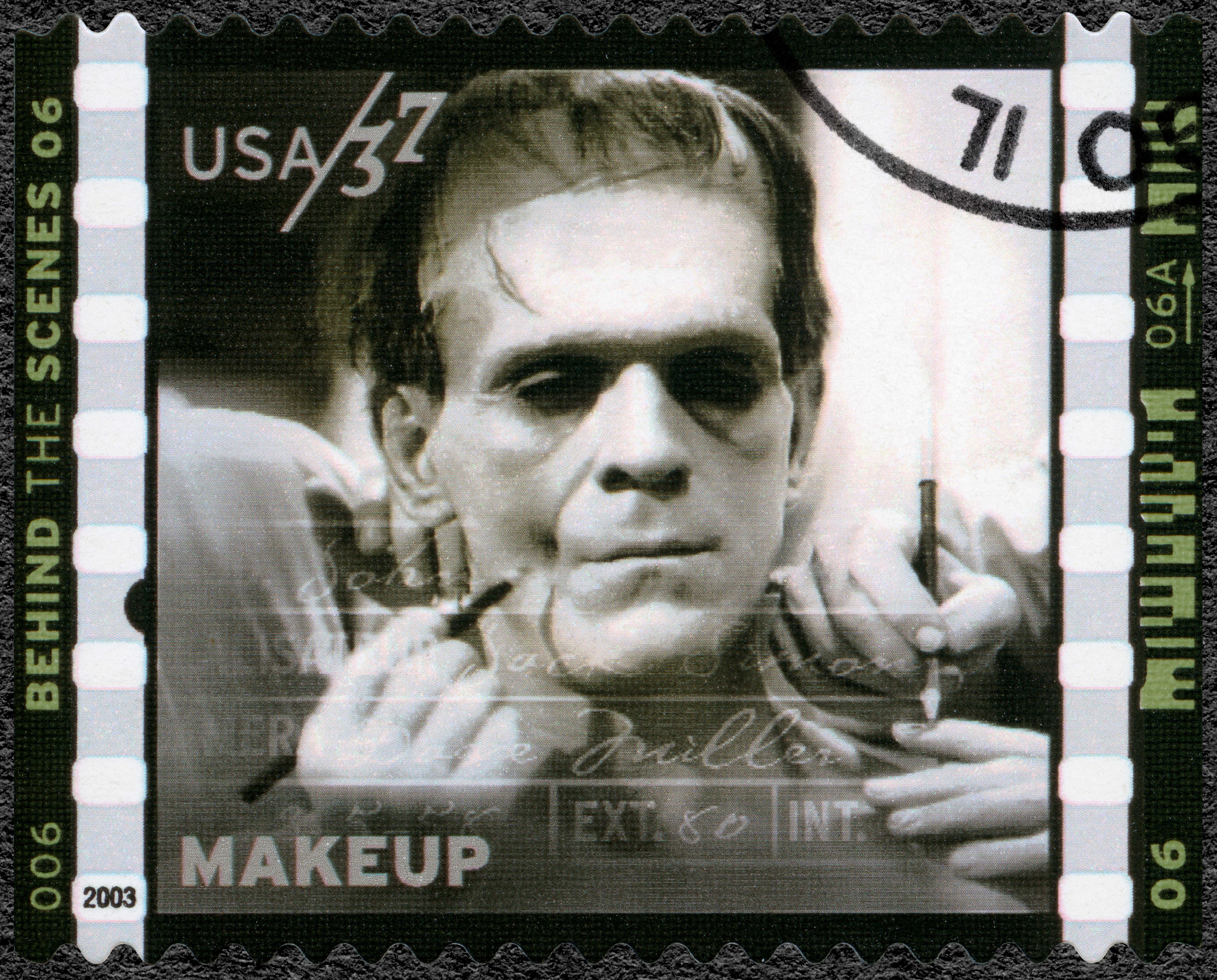

Another example would be the horror movie. The category of the horror movie as such did not initially exist. When Frankenstein came out, it was an instant success and Hollywood tried to elaborate a formula that would capture what was so successful. This is how the genre of the horror movie came about. It is a genre whose purpose is to provoke a very specific or a range of very specific emotions in the viewer. Or, think about music that is created in order to produce a certain affective mood or state. For the last 30 or 40 years, capitalism has worked very hard on creating affect and emotions. This is what I call “emodities”.

Photo by Olga Popova

The economic language of love

Let me take a third example, which doesn’t have to do with commodities as such, rather language and the type of language we use in order to think about our relationships. We increasingly use language that comes from the work sphere in order to conceive of our relationships. We talk about investing in a relationship. We talk about maximising our relationships. We talk about the costs and benefits of our relationships. This vocabulary comes directly from the economic sphere, from the capitalist sphere, and it intrudes on a sphere that did not use to be conceived of in economic terms, at least not these terms. It creates a telescoping of the semantics of the capitalist market and the semantics of the interpersonal sphere.

What the French philosopher Georges Bataille called “waste” – the idea that you can engage in a relationship that does not necessarily do you good, that can even destroy you; this form of relationship that does not serve any utilitarian purpose – has become foreign to our vocabulary. What has taken over the language of the psyche and interpersonal relationships is a utilitarian language of maximising our pleasure. Relationships which do not maximise our utilities – which do not “meet our needs”, as we commonly say – are increasingly deemed to be inadequate. So, there has been a historical encounter between the popular language of psychology and the semantics of the market.

Online dating and hyper-abundance

Let’s take a fourth and final example of the ways in which capitalism has colonised the world of relationships: internet dating sites. Technology is put to the service of big companies. And some of the fastest-growing companies on the internet are internet dating sites such as Tinder.

But what is more interesting is that sites such as Tinder present characteristics of capitalist modes of production. For example, one of the main attractions in these sites is the hyper-abundance of choice. Hyper-abundance of choice has been one of the clear mottos of mass consumer culture, of consumer production. The speed with which we are exposed to people and move from one person to another has been one of the chief organising principles of capitalist modes of production.

The extraordinary abundance of choice and the speed with which we approach and consume these choices are salient characteristics of capitalism. More specifically, they are salient characteristics of modes of mass production and mass consumption. All these examples show that it is difficult to disentangle our emotions, our interpersonal relationships, from capitalism because capitalism is so pervasive.

Can we separate emotions from capitalism?

In order to meet someone or have a relationship in a non-capitalist or less capitalist way, first, it would have to be a meeting in conditions of scarcity. By that I mean we would need to meet someone as though we did not have conditions of abundance of choice.

A second important element would be to approach relationships with non-utilitarian principles: not wanting to maximise one’s well-being, which also means being able to endure the boredom and the repetitiveness which often exist in long-term relationships.

Having said that, disentangling some aspects of the commodification of emotions might prove to be impossible and futile. For example, leisure now occupies too big a place in our personal life for us to disentangle it from our emotional life. So, leisure, which is an extremely important way to experience interpersonal relationships, probably cannot be disposed of. The same is true of psychology. Psychology is a therapeutic service, but it has also been commodified. This particular way of commodifying emotions is something that will probably stay with us, and which paradoxically is experienced as enabling us to be more authentic subjects. So, one of the great ironies or paradoxes of the colonisation of emotions and private life by capitalism is that it enables greater, not lesser, authenticity.

Discover more about

capitalism and emotions

Illouz, E. (2007). Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism. Polity

Illouz, E. (1997). Consuming the Romantic Utopia: Love and the Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. University of California Press.