So, although genteel, Jane Austen came from a very modest background and, indeed, like many young women of her day, had very little education. And yet her family, especially her father and several of those brothers, were bookish. The boys were educated, ambitious, enlightened and intellectually stimulating, and so in some ways, there were things there which prepared her to write; not least her father’s conversation and his large book collection, which she roamed through.

Jane Austen, an unlikely genius

Professor of English

- Austen pioneered a method of narration that combined authorial distance and irony with psychological insight. This allowed readers to see the world through her characters’ eyes.

- Reading Jane Austen at the peak of her powers is like reading mature Shakespeare. She’s no longer influenced by any other novelist, only by herself.

- Austen manages to make every character speak slightly differently and always reveal in everything they say the pressure of their own selfishness, folly or affections.

A modest but bookish family

Jane Austen was a clergyman’s daughter from Hampshire. She was one of eight children, with five older brothers and an older sister.

Jane’s father, who was a very important person to her, was educated but by no means affluent. He had to take in pupils and run a sort of school in the upper storey of his house in order to make money. He even ran a little farm in the field at the end of the garden.

Portrait of Jane Austen in watercolour and pencil. By Cassandra Austen. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

A novelist learns her trade

It’s important to note that by the time Austen tries her hand at writing novels, in the 1790s, writing novels is not such an unusual thing to do. There are a lot of novels around and she herself has read a lot of novels.

However, she’s unsuccessful in getting her novels published. We know that an early version of what became Pride and Prejudice was sent to a publisher and returned unopened, or certainly unread. Her short novel, Northanger Abbey, or, again, an earlier version of it, was purchased by a London bookseller but then never published. (Because he’d purchased it, the bookseller was quite at liberty not to publish it.) She wrote an early version of Sense and Sensibility called “Elinor and Marianne”, but again, it didn’t get published in book form.

So, there were these early, unsuccessful attempts, in her twenties, to become a novelist, as it were. In some ways, that was actually quite lucky for Austen, and maybe lucky for us, too, because it meant that when she came back to trying to write novels a decade later, in her mid-thirties, she’d already had lots of practice. She’d tried things out.

Getting inside the characters’ heads

Before Austen came along, novels of the 18th century had tended to fall into one of two types. The first type, written in the first person, would imitate something like a memoir, an autobiography or letters or journals. So, you got within the mind of a particular protagonist, but only within the mind of a particular protagonist.

The other method of writing was a kind of third-person narrative. You’ll find this in the novels of Henry Fielding, where the novelist is like God, talking to the reader in the easy, satirical, mock-learned style that the 18th century specialised in. Novelists like Fielding moved their characters around like pieces in a game, telling you everything and anything you wanted to know about them, but without getting inside their heads.

Portrait sketch of Henry Fielding. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. Original image is from a drawing by William Hogarth.

Austen happened upon, and I think to a large extent invented, a method of narration combining authorial distance and irony with psychological insight. These days, we usually call that “free indirect style”. What it means is narrating in the third person with a certain distance from the characters, but with the narration filtered through the consciousness of the characters.

Learning to love Jane Austen

I’m afraid it took teaching Jane Austen at university to convert me. I had the very common experience that individual readers still have with Austen when you reread one of her books and see something you’ve never seen before. How was that? I read this book not that long ago, but I didn’t see this.

If you teach Austen, students who are reading one of her novels for the first time will point out things you hadn’t noticed before in a novel you might have read half a dozen, or, in my case, a dozen times (in the case of Emma, my favourite, 16 or 17 times!). And yet in this finely worked machinery of the novel, you’re constantly making new discoveries, because Austen is so much more ingenious than we are.

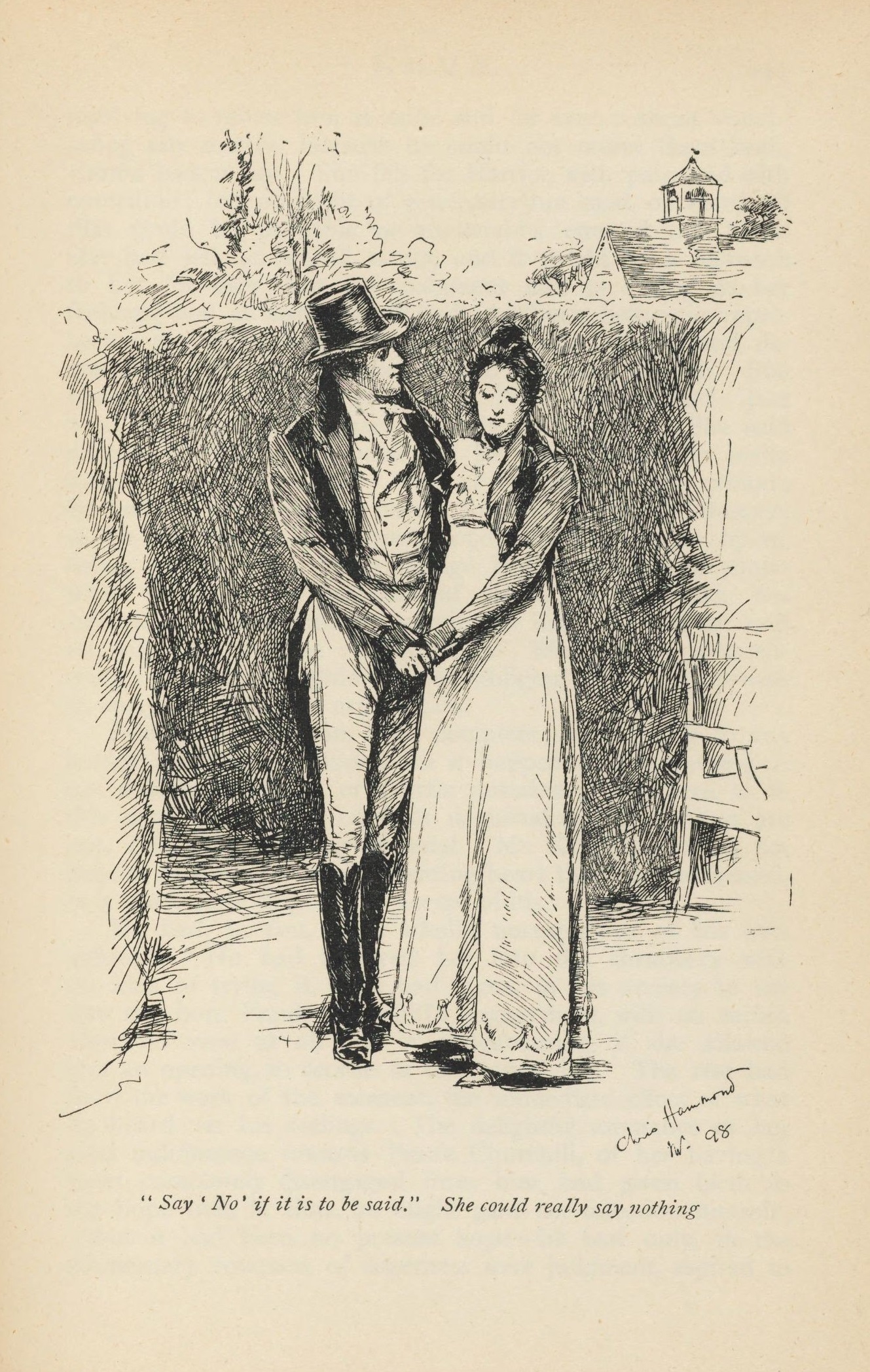

“Say ‘No’ if it is to be said. She could really say nothing” – an illustration by Chris Hammond of an 1898 edition of the novel Emma by Jane Austen (1775–1817). Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. By Christiana Mary Demain Hammond.

Emma is my favourite because I think it’s the novel she wrote at the peak of her powers. It was her penultimate novel. It’s like reading mature Shakespeare. It’s like reading Twelfth Night. She knows that when she writes Emma, she can do anything. She’s no longer influenced by any other novelist. She’s only influenced by herself. She’s only influenced by the last novel that she herself wrote, because her powers are so much beyond what other novelists have done before. She does this extraordinary thing of creating a novel where events are seen almost entirely through the eyes of a character, Emma, who’s wrong about almost everything.

Sparkling dialogue and romantic tension

Another way in which Jane Austen is an innovator and stylistic genius is in the framing of her dialogue. She manages to make every character speak slightly differently and always reveal in everything they say the pressure of their own selfishness or folly, or at least their own interests and affections. If you’re turning Jane Austen into something for the screen and if you’re watching it on television or at the cinema, the beauty and the wit of that dialogue just comes alive every time.

Jane Austen’s courtship plots also continue to fascinate. We know that the choices that her female characters make are absolute and decisive choices. She manages to turn to her advantage the manners, mannerisms and rigid conventions of her age, the restrictions about what can be said, what can be done, the fact that men and women can’t really touch each other. There might be a snogging at the end of the film adaptations, but there’s none of that in the books. They have to discover each other in more indirect ways. Wonderfully, in Pride and Prejudice, all the courtship between Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy is done in the presence of other people. When, in the first volume of the book, they find themselves alone together for the only time, Mr Darcy picks up a paper and starts reading it. They don’t say anything to each other.

These exceptionally constrained forms of communication gave a terrific drama to the exchanges. It’s not as if the modern reader is simply in love in a nostalgic way with a genteel, National Trust-ified, muslin-ised past. It’s the fact that Austen has managed to take the propriety and restraint forced upon young people in her own age and create out of that something electric.

Discover more about

Jane Austen

Mullan, J. (2013). What Matters in Jane Austen? Twenty Crucial Puzzles Solved. Bloomsbury.

Austen, J. (2019). Sense and Sensibility. (J. Mullan, Ed.). Oxford World’s Classics. (Original work published 1811).

Mullan, J. (2006). How Novels Work. Oxford University Press.