The world’s largest democracy

India, of course, is the world’s largest democracy. It’s home to 1.2 billion people, the second-largest Muslim population globally and a staggering number of languages.

But there’s more to Indian democracy than its sheer scale. It is also a country that made significant innovations in the mid-20th century on questions around welfare, equality and, what people in the West call, multiculturalism: how to live with people who are not like you, who profess another religion or speak another language.

In Western democracies, these are questions that have become very pressing in our time because of the traditions of consensus and uniformity. In the West, nationalism tends to derive its strength from a push for uniformity in language, race or the like.

An unlikely democracy?

In India, these kinds of trends are entirely reversed. Indian democratic ideas and institutions had to address questions of inequality and diversity right from the get-go.

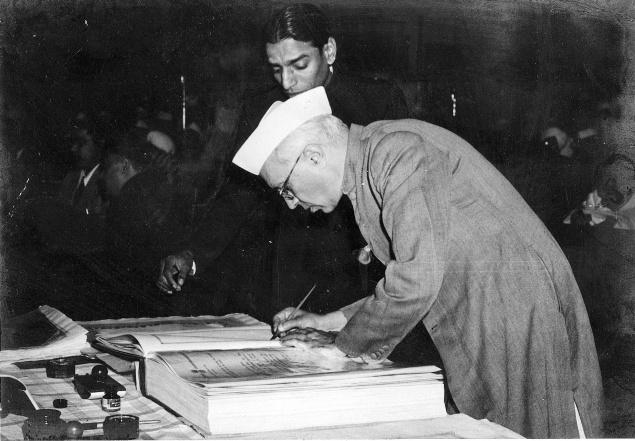

How did this work in practice? We could look at the State’s architecture and analyse how the judiciary relates to the executive, how legislators represent the people and so on. But what interests me the most is that for a country like India – poor, devastated by war and famine, with a long history of colonialism – there was very little reason to have faith in democracy. And yet, that is exactly what India did in 1950, when its constitution became official.

Where does Indian democracy come from? Is it something ancient? Is it something that the British gave? The standard idea is that the representative structures implemented by the British laid the foundations for India’s democracy. But that’s just part of the picture. The real mover and shaker of India’s democracy was Gandhi, the father of the nation. That’s not because he theorised about democracy. On the contrary, he despised the parliamentary system. He called the parliament a “prostitute”. The reason I name Gandhi is that he developed a very precise grammar for democratic action and democratic subjectivity, which are the most important things.

Breaking salt and the abstract language of politics

Gandhi’s most famous campaign was the Salt March, or the Salt Satyagraha. It’s something he devised and planned from his ashram. In between campaigns, Gandhi would retreat to his ashram, which was devoid of books and other distractions. There, Gandhi lived by a set of self-abrogating practices such as fasting, silence and celibacy.

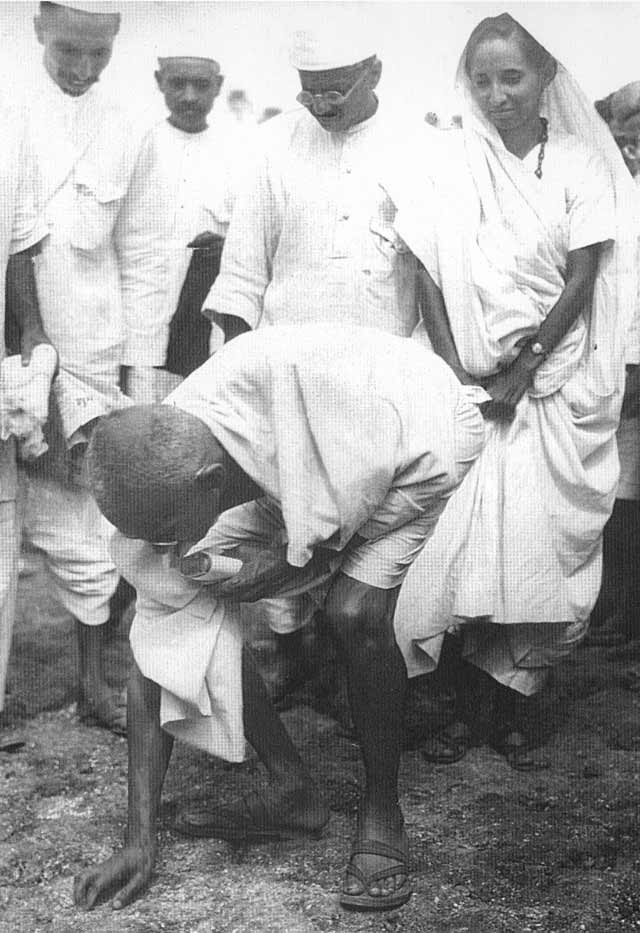

Gandhi decided to build a campaign around salt because he recognised that it was a necessary commodity. It was also a British monopoly that was prohibitively taxed. Gandhi’s idea was to walk 70 miles to the seashore from his ashram, and he called on his followers to join him.

By the time he reached the shore, tens of thousands, if not a hundred thousand people, had joined him on what became known as the Dandi March. This was a very simple political action, but it required individual will, which Gandhi was calling for. He was instituting a highly visible grammar of political action.

Gandhi arrived at the seashore and broke salt in public. That was an offence. On one level, he demonstrated that the people closest to the salt were the least able to access it. On another, he was doing something to break the abstract language of politics, which tended to be spoken about in big ideas like liberalism or communism. Gandhi interrupted this abstract language and pioneered a different way to communicate political ideas.

Between life and death

Let’s take the example of fasting. Of course, fasting is an individual practice that Gandhi undertook, but he was also trying to show that this was a liminal space between life and death.

For Gandhi, the question of death is fundamental as the basis of politics. According to him, death is the only human capacity that is beyond exchange. No one can die in your place. You can die for a cause that is greater or lesser than your own, but choosing to die is the most individualistic of actions.

This was a starting place for Gandhi’s politics. Fasting represented the difference between the addictive qualities of life (what we would now call consumerism) – which he thought the British were all about – and death. Above all, his frail body became a symbol of the famine and food insecurity that were bywords of British colonialism in India.

The enduring power of Gandhian principles

Gandhi’s contemporaries would give statistics and say, this is how much the British have plundered. That was all very well, but when you had this frail man fasting, people understood it. It laid the foundations for social movements, collective action and a strong moral-political vocabulary.

This lay outside any Statist or liberal cage. It wasn’t a politics you could easily measure by the calculus of self-interest. As a result, India is and will remain democratic. As we speak today, India is run by its most authoritarian prime minister in its 70-plus-year history, but its people have delivered verdicts against him in several States amid a deadly pandemic.

Or take something like Indian environmentalism, based on very Gandhian principles, with activists resisting developments by standing where waters are being moved or trees felled, putting their lives on the line. This dates back to the 1960s and 1970s, long before anyone had heard of Extinction Rebellion.

Father of the nation

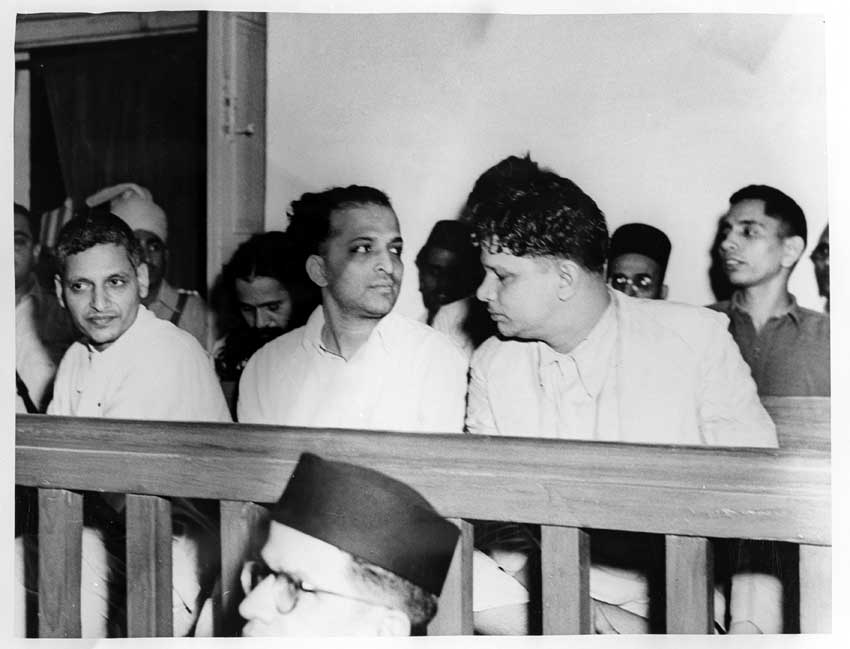

Hindu nationalism, or Hindutva, was really Gandhi’s nemesis. It was a believer in Hindutva who assassinated him in January 1948, just four months after Indian independence.

In his confession, the killer said that Gandhi had proved to be the “Father of Pakistan”. This is a commonly held belief in the world of Hindu nationalism. On one level, it’s naive and silly, but, on another, it’s profoundly important and deserves to be unpacked.

Right from the beginning, India had been conceived, politically, as a mother: Mother India. But, in a way, Gandhi’s assassination installs him as the father of the nation. People had long called him Bapu, which means loving father, but it’s really his assassination that confirms his status as a father.

I’m borrowing heavily here from Freud’s work on the origins of monotheism, the idea that there’s a mythic parricide at the heart of all clans and communities. In a way, that’s what Gandhi’s killing signifies: the birth of a new fraternity of family. As a result, the father is not only banished but also incorporated into the mythic structure of the nation.