I think that the only way that this trend can be reversed is if more traditional, mainstream, evangelical, pentecostal, Christian leaders turned their backs on politics for a while. Instead of trying to win the culture or change the culture, as some evangelicals like to say, if they could focus on building the kingdom – by which I mean re-establishing some degree of control and cohesion within their own movement – they would be able to bring the people in their pews back to a deeper, humbler and more complicated understanding of the religious tradition that they claim to belong to.

Religious nationalism in the United States

Professor of Sociology and Religious Studies

- Land, peoplehood and political sovereignty are the three crucial ingredients of modern Western understanding of nationalism.

- Christian nationalism is one of the most important currents within American politics.

- Black liberation theology is patriotism in the sense of devotion to a particular set of principles, above all, equality – that all men, all women and all races are created equal – and a broader commitment to social justice and inclusion.

Defining religious nationalism

My view is that Western nationalism is deeply rooted in a certain Christian understanding of Hebrew scripture, one that connects land, peoplehood and political sovereignty – the three crucial ingredients of modern Western understanding of nationalism. You have a people, and they have a territory over which they rule collectively or over which they have sovereignty. That is in many ways the definition of nationalism. Interestingly, almost every country that exists today in Western Europe, at some time to some degree, made a claim to be a new Israel or a new chosen people. This was the template or frame that was used to think about people who had within Western Europe this Christian appropriation of Hebrew scripture.

So, in a sense, one can’t really draw a completely sharp distinction between religion and nationalism. That’s not to say that there aren’t secular versions and understandings of nationalism in the contemporary world. It’s simply to say that they have a religious unconscious that can always be summoned to the fore. Western understandings of nationhood will resonate with religious people in a particular way.

One possible form that nationalism can take in and beyond the contemporary West is a religious nationalism in which peoplehood is understood in terms of religion, in which territory is understood as sacred in the form of a promised land, in which sovereignty is understood as submitting to divine law.

Why Christian nationalism is so pronounced in the US

One of the most influential groups of early immigrants in the United States was the New England Puritans. They literally understood themselves as the chosen people, and their persecution under English kings to be analogous to the enslavement of the Israelites by the Pharaohs. They believed their emigration across the ocean to the United States to be like the crossing of the Red Sea. They thought that it was their calling to build a “city on a hill”, in a famous phrase that you still hear today in American political discourse.

Nationalism and national identity of the United States have always been shot through to some degree with religion. This is in part because there could not be a myth of common ethnic origin in the United States in the way that evolved in many of the nation-states of Europe: immigration was always a reminder that Americans were a nation of nations, a hybrid of different peoples.

How Christian nationalism influences American politics

Christian nationalism is one of the most important currents within American politics. It is a current that for much of the last 30 or 40 years flowed underground, in a way that it remained largely invisible to those outside of the fold. It burst into view under Trump and exploded during the Capitol insurrection, where you saw precisely this mix of Christian nationalistic white supremacist symbolism.

You saw people wearing crosses, carrying Trump flags and American flags, wearing explicitly neofascist or white supremacist garb. A lot of people looked at that and they thought, you know, that is apples and oranges: those things don’t go together. My response, on the contrary, is, that is not apples and oranges – that is a fruit cocktail. White Christian nationalism is a tradition which is far older in the United States than almost any other rival political tradition. It’s certainly much older than Lockean liberalism, universal human rights or even democracy – it goes back well into the 17th century in the United States.

Washington, DC, January 6, 2021: American and Trump 2020 flags installed by pro-Trump protesters on the Capitol building. By lev radin.

What is the relationship between religion and patriotism in the United States?

White Christian nationalism sees the United States as a Christian nation founded by Orthodox Christians based on biblical principles – Protestant principles – by reason of which the United States has been uniquely blessed with power and prosperity. Yet, this power and prosperity is under threat, and can be withdrawn if America somehow drifts away from these founding principles, if it becomes less white, less Christian. “Whiteness” serves as a kind of substitute ethnic identity, under the premise that it was originally a white nation.

There’s a different way of thinking about religion and patriotism, which I think has been most powerfully and most vociferously articulated within the tradition of Black theology and the tradition of the Black Church. Interestingly, just like the Puritans, many enslaved Black Christians in the United States also came to understand themselves through this Old Testament lens – they really were enslaved by a despotic power and were at some point liberated through revolt against slavery. They did undergo a great migration, a sort of exodus to the north following the war. This tradition of Black liberation theology is much less about national power. It’s not patriotism in the sense of the worship of national power, of American prosperity, of the American military, for example. It is patriotism in the sense of devotion to a particular set of principles, above all, equality – that all men, all women and all races are created equal – and connected to that, a broader commitment to social justice and inclusion.

How recruitment into nationalist groups works

An important question that arises out of the events of 6 January 2021, the Capitol insurrection, is how do people get recruited? I think we have much to learn about this. Many scholars and journalists are focusing on who actually showed up at the insurrection, who broke into the Capitol, how they got radicalised and what role Christianity and their Christian self-understanding might have played.

There are probably different pathways. There are definitely cases in which people embedded in a particular church, who were observant Christians, got radicalised often via the big lie about the stolen election or the QAnon conspiracy, according to which the United States government is run by pederastic, Satan-worshipping Democrats. All of this is in part, of course, through the algorithms on the internet, on YouTube and on Facebook and so on, which, in order to sustain our attention and keep us clicking, push people towards more and more radical content – in whichever direction that may happen to take them.

Washington, D.C., United States – January 6, 2021: President Donald Trump supporters storm the United States Capitol building. By Thomas Hengge.

Other pathways that lead people to join these groups

I think that there is another pathway, which is that people who start out as racists or white supremacists and want to put a religious veneer on their views, try to give their views some moral legitimacy that they certainly don’t deserve. Those folks will often cast themselves as defenders of God.

There is a third pathway, and this one is more for leadership. What one increasingly sees within religious life in the United States is people rising to prominence as national religious leaders, not by going to seminary, not by rising up through the ranks in a particular denomination or religious community, but through their political connections, through their social media presence and through developing a kind of personal brand.

Meet the religious influencers

I can give you two very influential examples of people who have come to prominence via that path. One is Eric Metaxas, who graduated from Yale with a degree in English and who clearly had ambitions to be a public intellectual. He published a couple of books that were reasonably well reviewed, but in his insatiable thirst for public attention, he adopted more and more radical views. Most recently, he spoke at the Capitol insurrection, essentially saying that he was willing to become a martyr for Donald Trump.

The other example is Paula White, the pentecostal pastor and megachurch leader who, for many years, served as the “spiritual adviser” to Donald Trump; someone who has no theological education, who founded a megachurch down in Florida, developed a larger and larger media presence, and came to full national prominence through this accidental connection she had to Donald Trump. Media presence and political access, not denominational credentials or a theological education, is the basis for becoming a religious leader.

Practice what you post

These are people who are not accountable to a particular community of faith or set of peers and are not embedded or trained in a deep or thick theological tradition. They don’t really understand the full complexity and richness of the religious tradition that they claim to speak for and are therefore prone to take extreme views, views that will get them attention and clicks and likes.

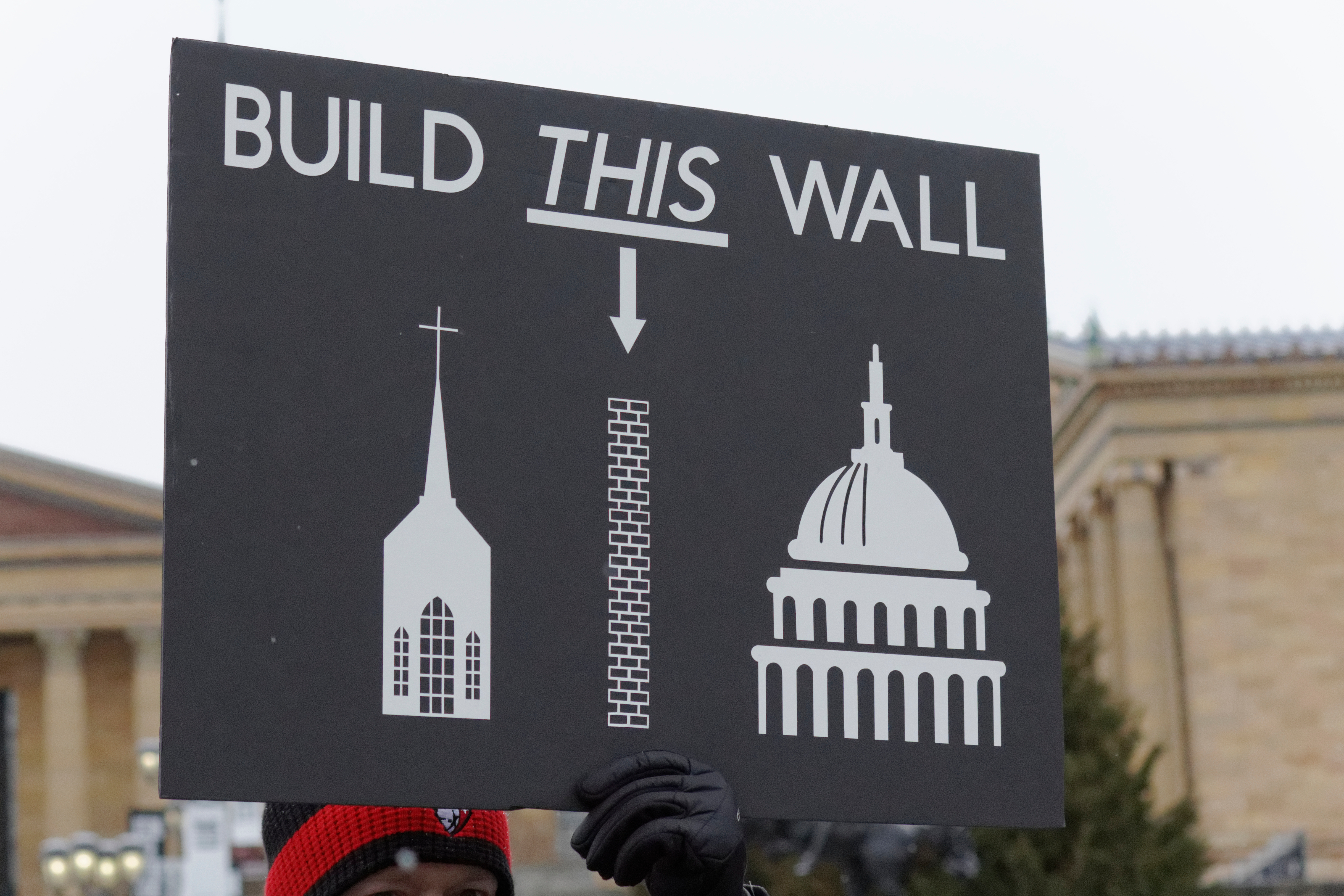

Philadelphia, PA/USA – January 18, 2020: A sign mocking Donald Trump’s border wall and supporting separation of Church and State is seen at the fourth annual Women’s March on Philadelphia. By Jana Shea.

Religious nationalism around the globe

Religious nationalism in the United States gets a lot of attention, but it’s not something that is unique to the United States. What we see in many of the Western European far-right and right-wing populist movements are similar appeals to Christianity or Christian civilisation or Christian identity. Of course, the context in Western Europe is different because these are societies in which far fewer people are observant Christians today than in the United States. Yet, I think the motivation is similar. It is a way of dressing up nativist, racist, authoritarian, reactionary politics as if they were somehow high-minded and moral and noble, which they most certainly are not. There is even convergence between the far right in Western Europe and the far right in the US.

If you look at the Hindu nationalist movement and the Hindu right in India, under the leadership of Modi – if you look at ErdoÄŸan’s regime in Turkey – if you look at Duterte in the Philippines, what explains this resurgence of far-right-wing politics and its alliance with religious nationalism?

I think there are a couple of things to point out. One is the manifold dislocations that have followed in the wake of the process of globalisation over the past three or four decades. The disruption and dislocation that many people have experienced has created a nostalgic yearning for a lost community coherence and, increasingly, a willingness to line up behind a strong leader who will restore that mythical golden past. We are also seeing increasing numbers of religious leaders who are prepared to act as allies with these far-right-wing movements.

Discover more about

the rise of religious nationalism

Gorski, P. (2017). American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present. Princeton University Press.

Gorski, P. S., Kyuman Kim, D., Torpey, J., et al. (2012). (Eds.). The Post-Secular in Question: Religion in Contemporary Society. NYU Press.