The New Deal order departed from long traditions in American life. It departed from the idea that freedom was freedom from government. The New Deal order said that freedom could only come through government. The problems of industrial society had become so great, and capitalism had become so chaotic that there was no alternative but to do something against the grain in America, which was to build a strong and powerful State to manage capitalism in the public interest.

The new America's political order

Paul Mellon Professor of American History

- America has had two political orders since the 1930s. The New Deal order arose in response to the Great Depression and lasted till the 1970s; the neoliberal order that replaced it began to come apart in the wake of the Great Recession of 2008.

- Thirteen years on from the Great Recession, we see the disintegration of the neoliberal order as it comes under attack from political movements like populism and ethnonationalism.

- The eclipse of neoliberalism coincides with a desire – expressed by both Obama and Trump in their different ways – that America rethinks its place in the world and no longer play the global policeman.

Capitalism in the public interest

Over the last 80 years, America has had two political orders. One was a New Deal order that arose in the 1930s and disintegrated in the 1970s. The other is what I call the neoliberal order that emerged out of the debris of the New Deal order in the 1970s and seems to be coming apart in 2021.

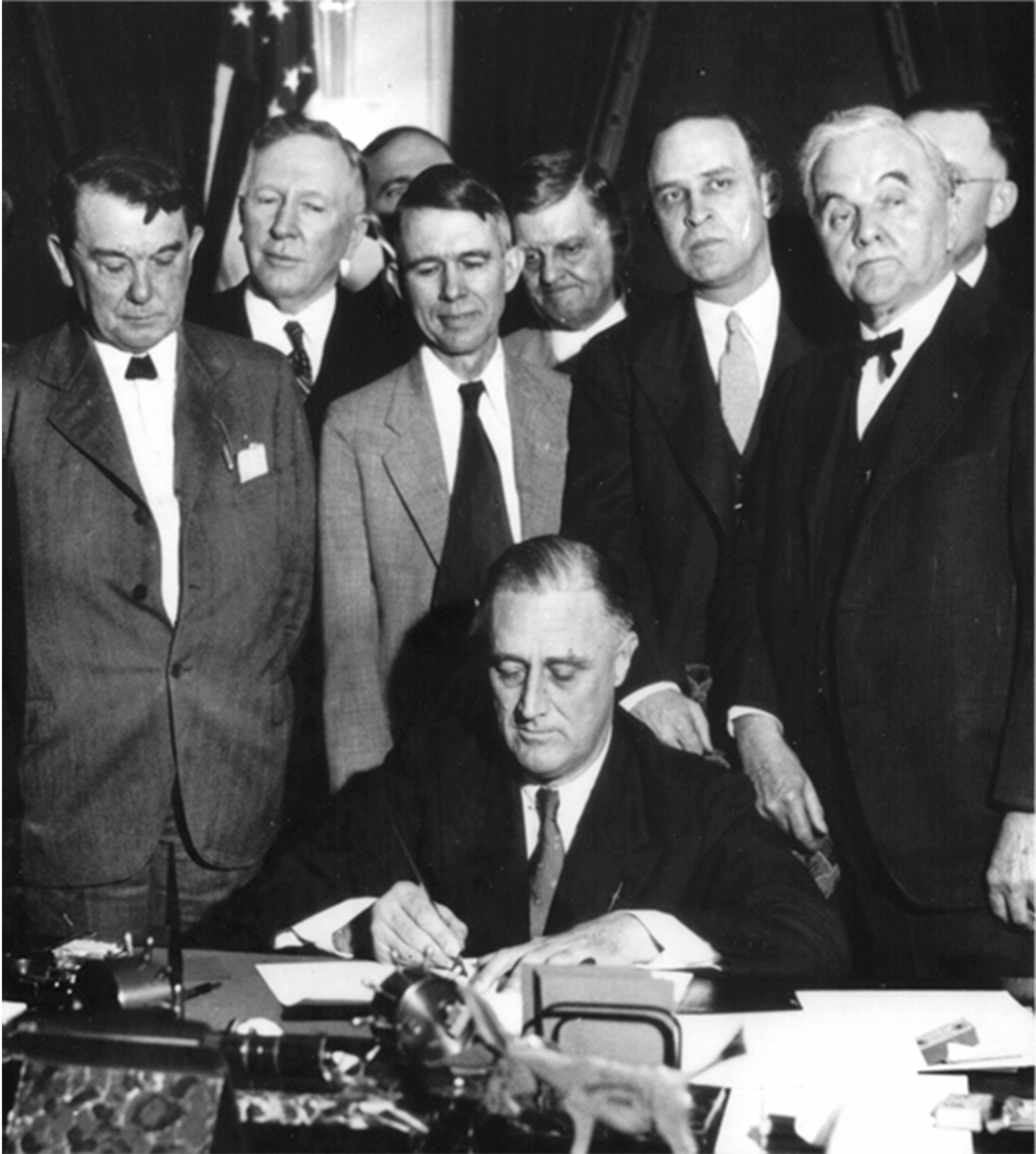

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the TVA Act, which established the Tennessee Valley Authority. The TVA was created by Congress in 1933 as part of his New Deal. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Freedom through government

The New Deal order was a response to the Great Depression, which lasted from 1929 to 1941. The big State built during that time to manage capitalism continued through the Second World War and was sustained throughout most of the Cold War.

The crucial principle of this political order was that capitalism and markets could not be depended on to work without government management, assistance and oversight. This was not socialism, although at times, it came close to social democracy. But it said that the government was indispensable to managing the economy in the public interest.

The New Deal order also elaborated a certain idea of freedom and liberty that went against the classical idea of liberty, which was freedom from government, monarchies and aristocracies and being free to operate in the economy as we wish. Those are the circumstances in which we'll be able to enjoy our freedom in the fullest sense. By contrast, what the New Deal says in the 1930s is that that moment has passed. People do not have enough resources to enjoy their freedom. People need a big government to manage the economy in the public interest to give people basic security. To enjoy a full and free life, people need welfare in times of distress and disability, as well as education and other opportunities.

The rise of Reaganism

This is the moment when the meaning of liberalism in America changed from liberty from government to the liberalism of the New Deal and the Democratic Party. The New Deal order said that, in order for us to be a liberal society of diverse individuals enjoying our freedom, we need a big State to manage the economy and give individual Americans the resources they need to thrive. This politics emerges with Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s, dominates America in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, and then falls apart in the 1970s for a variety of reasons.

In its place emerges a neoliberal order. It can't just be called a liberal order because the Democrats and Roosevelt had taken the name “liberal”. So they call themselves neoliberals, by which they mean they want to recover the original 19th-century promise of liberalism, which is that freedom and individualism would flourish only in circumstances in which State regulation was taken apart and even destroyed. Their tribune is Ronald Reagan. They rise to power in the 1980s, after a period in which the American economy had been troubled. They preach that if we simply get the government out of economic life, the economy will flourish. And it will achieve its greatest aspirations and greatest prosperity.

The neoliberal mission

In addition to getting the government out of private and economic life, neoliberals also argued for abolishing borders limiting trade, for the free movement of people and for the ability of capital and information to travel all over the world instantaneously. Made possible by the IT revolution, it was a dream of a world transformed by market relations. It reignited belief in market perfection – so long as these markets were freed from the State and public oversight.

This doctrine becomes so popular that it overwhelms Britain in the 1980s and 90s under Thatcher and America under Reagan. Bill Clinton buys into it, as does a good part of New Labour under Tony Blair. It is the primary and dominant system in the Anglo American world and much of the rest of the world through the first decade of the 21st century.

The NYPD and news crews stand watch outside the New York Stock Exchange on 30 September 2008, the day after the record-breaking 777-point drop in the Dow. Photo by Steve Broer.

The problems for neoliberalism begin with the Great Recession of 2008. Just as the Great Depression of 1929 began to unravel a political order that preceded the New Deal order, so the Great Recession of 2008 begins to unravel the neoliberal order and raise questions about political alternatives that have been shut out of the conversation for a long time. And now, 13 years on from the Great Recession, we are seeing the disintegration of the neoliberal order and the emergence of something new and different in terms of politics and economics.

Make authoritarianism great again

The world is changing fast. Certain principles that could not be challenged in the heyday of neoliberalism are now challenged every day. We used to regard free trade and the free movement of people as principles of global economic life. We felt similarly about the free movement of information, which allowed us to contact anyone in the world instantaneously, day or night. That’s still technologically possible, but more and more countries are creating their own self-contained information systems. We have not yet seen extensive controls on the free movement of capital, but it is now easy to imagine that they will soon exist.

We are, in a sense, retreating from the age of globalisation, with tribalism and ethnonationalism resurgent on the world stage. In the United States, that's what Trump is about. In the U.K., that's a large part of what Brexit is about. In Hungary, there’s Orbán. In Russia, Putin. In Turkey, Erdogan. In India, Modi. In the Philippines, Duterte. In Brazil, Bolsanaro. The list goes on.

In the politics of these different countries, we see the emergence of something that runs contrary to both the New Deal and the neoliberal orders. We see enthusiasm for authoritarianism and frustration with democratic forms. We see a belief that liberal democracy has brought the world much more grief than satisfaction. We see a yearning for a strong, tough leader who will not obey the niceties of constitutions and respect the rights of little minority groups who should be pushed aside. We see a determination to act decisively to set things right (and setting things right often means putting one ethnic, religious or national group in charge of every other).

All this echoes the 1930s and the rise of fascism when there was a similar sense that democracy was on the defensive. So the authoritarian, right-wing, ethnonationalist path to the future has become very clear, and it is embodied in Trump and Trumpism. There are ways in which the climate crisis may only intensify that tendency because walls such as Trump’s infamous border wall will be a technique of politics and control in an age of climate change.

Leading from behind?

As I look at the United States, I see continuity between Obama and Trump. Obama issued the famous line: We want to lead from behind. Well, you can't lead from behind. It's an oxymoron, an awkward expression of his desire to say that America can't be everywhere and manage everything.

Transfer of Qayara Airfield West from Operation Inherent Resolve to Iraqi security forces, 26 March 2020. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Trump, for all his confrontational style and belligerence, has not wanted to go to war. He has also been determined to withdraw American troops from the world and for America to go it alone. So there is a kind of continuity there, and I think we can expect America to continue to rethink its place in the world.

Powerful voices in American society and politics are now saying that America needs to be more modest. It needs to withdraw and no longer play the role of global policeman. I say this fully cognisant of how many hundreds of thousands of American soldiers are still overseas, stationed at hundreds of American bases around the world. The footprint that the U.S. built up during the Cold War and the age of Pax Americana is immense, and it is going to take quite a long time to unravel that and build something different. But I do expect in 30 to 50 years that the world will be governed internationally by three, four or five major powers. Not by one. So in that sense, the end of neoliberalism or the neoliberal order is also about the end of a certain period of American domination of the world.

Discover more about

the decline of neoliberalism

Gerstle, G., Lichtenstein, N., & O'Connor, A. (Eds.). (2019). Beyond the New Deal Order: U.S. Politics from the Great Depression to the Great Recession. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Gerstle, G. (2018). The Rise and Fall(?) of America’s Neoliberal Order. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 28, 241–264.