The issue of the relationship between American capitalism and slavery has been fundamental to American historiography. It’s something that American historians have thought a great deal about. That’s partly because it speaks to fundamental assumptions about what capitalism is about, what modernity is about and what the United States is about. Is capitalism, for example, about markets, trade, entrepreneurship and innovation? Or is it fundamentally about coercion, exploitation, colonialism and violence? Historians have been debating this question for a very long time.

American capitalism and slavery

Senior Lecturer in American History

- Historians traditionally regarded the American North as industrialised and the South as rural; however, the South was in some ways at the cutting edge of modern capitalism.

- American slavery and the production of raw cotton was key to the Industrial Revolution in Europe.

- Capitalism is compatible with a variety of labour systems and uses of violence.

The question of capitalism

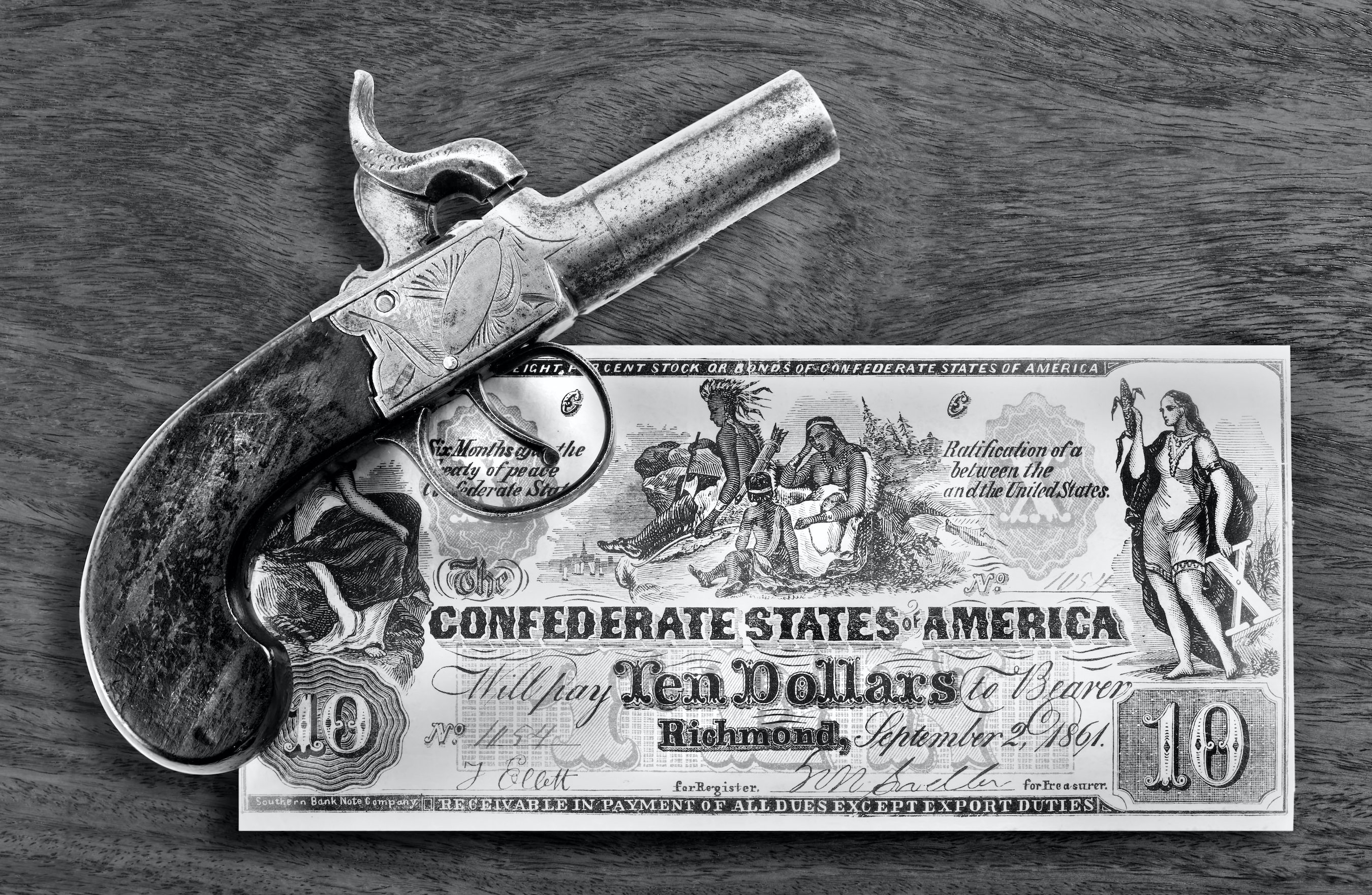

Photo by APHITHANA

Traditional views of North and South

The traditional view was to think about this question in terms of North and South. The North was the progressive part of America. It industrialised, urbanised and embraced new technologies. It marched with the times. It marched with progress. The South was cast as the fundamental opposite of that. The South was agrarian, traditional, rural; it did not urbanise or have big cities, and there were no factories, no signs of industrialisation.

Slavery was cast as an institution that was at odds with modern capitalism. Modern capitalism was about wage earners marching into factories. Slavery was an institution that in some ways, kept Southern society traditional. Planters were not viewed as modern businessmen; they cared somewhat more about their identity as masters, as lords of their estates. They were cast more like feudal lords than modern businessmen. Plantations were viewed as feudal estates, not like modern factories and not geared to maximise production.

Industrial capitalism in the South

Over the last generation or so, there has been a total reversal in how historians have considered this question. Historians went back to the archives, and to their surprise, they realised that the South was very different from the caricature that they were initially taught. The South was at the cutting edge of modern capitalism to some extent.

Plantations were commercial units that were geared toward maximising production. Slavery was an efficient way of mobilising workers on the plantation and of maximising production. Planters were calculating businessmen. They kept very detailed accounts of the slaves’ labour. They constantly tried to increase the productivity of those slaves, and they were incredibly successful at doing so.

There has also been a rethinking of the South’s place in global capitalism over the last generation. Rather than being a remnant of an earlier order, a more traditional society, historians have recently emphasised that the American South was fundamental to industrial capitalism globally. Slave plantations provided the raw cotton that flowed into textile factories in Europe. In many ways, they made the Industrial Revolution possible in England and the West more generally.

American slavery and the Industrial Revolution

Photo by Christopher Winfield

When we learn about the Industrial Revolution, this is primarily a story about European factories and technological progress, mostly focused on the English context. However, what often gets left out of the story is the question of raw cotton. We know that industrialisation, especially in its early phases, rested on vast supplies of raw cotton flowing into English factories. What were the viable sources of supply for this type of commodity that, of course, could not be grown in the European context?

It’s quite striking that this supply came from the American South. When we think about the relationship between European industrialisation and the vast expansion of the so-called Cotton Kingdom in the American context, we understand the centrality of slavery to the emergence of modern capitalism. This is one of the bottlenecks that often gets left out of the story partially because there was no technological solution to this problem. While you could process, spin or weave cotton using machines very efficiently, there was no mechanised alternative to the production of raw cotton. In the early 19th century, what you needed was a lot of land and a lot of labour.

Land, labour and cotton

A lot of indigenous land in the US proved to be very fertile soil for the cultivation of raw cotton. Americans in the American South realised this fairly quickly after Independence and moved to remove the indigenous populations using violent means. Around the time of the American Revolution, American slavery was in a lull; at that time, many of the Founding Fathers were calling for the end of slavery. Nevertheless, a lot of that slave labour was redeployed away from earlier colonial crops into the production of raw cotton.

This is how the American South emerged quite connected to European industrialisation. Historians have thought about whether there could have been alternatives. Perhaps, cotton could have been grown using free labour instead of slave labour. Or, perhaps, some other region in the global economy could have been the provider of this raw commodity that was suddenly in great demand due to the Industrial Revolution.

However, it’s tough to imagine a scenario in which the scale of the operation and production and the amount of land that was necessary could have transpired voluntarily in some other region of the world economy. It’s difficult to think that this could have occurred freely, without the use of force and coercion first to grab the land and then to mobilise the necessary labour to produce such huge amounts of cotton.

The rise of American capitalism

As we gain a greater appreciation of the centrality of cotton to global capitalism in the early half of the 19th century, there’s also greater appreciation or reassessment of cotton’s role in the rise of American capitalism in the American economy. In the first half of the 19th century cotton was the number one American export – it once added up to more than half of all American exports in value. The people who benefitted from this trade were not confined to the American South. It wasn’t a regional system; it was part of an American national system.

The dominant merchants in New York City were knee-deep in the cotton trade. They benefited from trading in cotton, insuring slaves, providing mortgages to planters and extending credit that facilitated the expansion of the Cotton Kingdom. It’s troubling that we can easily trace the emergence of Wall Street and the financial sector of the American economy in the early part of the 19th century to the profits of the cotton trade and the cotton economy.

Slavery and capitalism

Photo by W.Scott McGill

In this debate about the relationship between slavery and American capitalism, the traditional view of slavery holds that it was incompatible with modern capitalism in some ways and was something that stood in the way of modern economic progress. However, this view is highly flawed and has been fundamentally revised by historians. The opposite perspective that emphasises slavery’s total compatibility with modern capitalism is also exaggerated.

In 1858, James Henry Hammond, a pro-slavery Southerner, gave his famous “Cotton is King” speech on the floor of Congress, where he made the argument that global capitalism could not survive without slavery. He predicted that if the North tried to go to war against slavery, the South would secede and ultimately win the war because the global economic order would collapse. This prediction proved to be wrong.

It’s important to remember that slavery ended, and capitalism survived. While we have a greater appreciation for how slavery and capitalism can be compatible and reinforce one another, it’s important to remember that slavery was ultimately dispensable. New labour systems came, pushed slavery aside and offered other alternatives, which were exploitative in their own way. They generated new forms of inequality. However, they weren’t built on the same use of private violence by employers against their workers.

Capitalism and inequality today

It’s important to continue to think about the relationship between slavery and capitalism because we need to understand that capitalism is compatible with a variety of labour systems. It’s compatible with different levels of violence. It’s compatible with all sorts of features of our society that we would perhaps like to change.

Therefore, capitalism, on its own accord, is not going to replace or remedy some of these inequalities. Rather, we have to take action to address them. There’s nothing in the history of capitalism and slavery that would suggest that capitalism would address questions of racial disparity and other types of inequalities within society. On the contrary, we have a lot of evidence that capitalism moves to mobilise those types of disparities and take advantage of them.

Discover more about

American capitalism and slavery

Beckert, Sven. (2015). Empire of Cotton: A New History of Global Capitalism, Penguin.

Rosenthal, C. (2018). Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management, Harvard University Press.