Genesis and generation, it’s all part of the same story, whether it’s the universe or a family or a set of crops. Reproduction was a word that had a whole different set of meanings that weren’t really stable until sometime in the middle of the 1700s, when it came to mean, as set out by a particularly famous French natural historian, the making of, in a much more almost mechanical sense of the perpetuation of a species, one from the next. Hence, it is much more like copying. It happens without this kind of active generative quality that is part of a generation. So, there is this shift from generation to reproduction where reproduction becomes something much narrower. Minerals do not reproduce. Plants, animals and humans all reproduce, and the line can be seen as one moving to the next.

A brief history of reproduction

Chair in History of Science

- Reproduction has a history, like everything else. Reproduction is different from genesis in that reproduction is purely copying, and genesis is the active creation of everything from minerals and plants to animals and humans.

- The question of paternity mattered enormously for financial and inheritance reasons, and resemblance was often explained as a result of “maternal imagination”.

- Ensoulment was the idea of when a child became a child, and the exact moment was often debated.

- Medicalisation of childbirth is a story of great progress set against a history of it being seen as a bad thing in which women lost knowledge and control of their own childbirth processes.

Generation and reproduction

Everything has a history, even how babies are made. We think about reproduction as something which is self-explanatory. It’s not. The notion of reproduction has a history, and it’s a history that is often paired with the history of generation. So, what’s the difference between the history of generation and the history of reproduction? What’s the difference between generation and reproduction?

Generation is the active creation of everything from minerals and plants to animals and humans. It’s a very active making. Reproduction is more like copying, and reproduction – generation – was the way that propagation was understood through much of history.

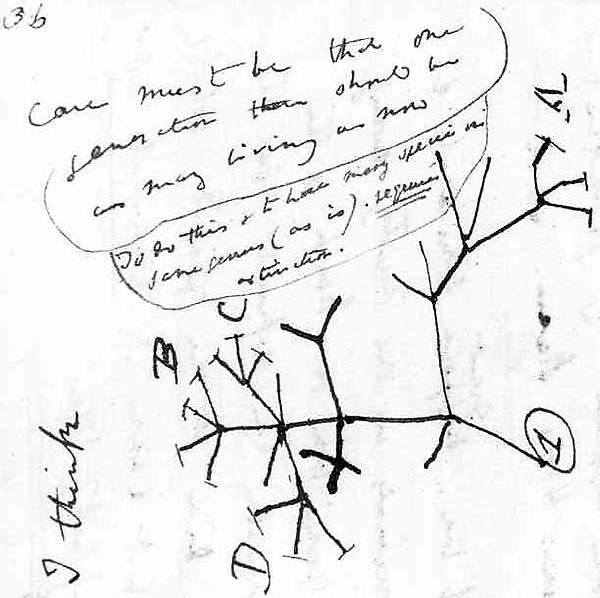

Charles Darwin’s first diagram of an evolutionary tree from his First Notebook on Transmutation of Species (1837) on view at the Museum of Natural History in Manhattan. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Baby-making and resemblance

Most people in early modern Europe associated the making of babies with sexual intercourse in some form or another – that wasn’t a mystery – though, there are people who argue that there are groups of people in the world who do not make the link between getting pregnant and having had sex. The questions that people exercised in early modern Europe were about when life began, when ensoulment (that was their definition of when life began) occurred and when and why one offspring might resemble a parent or not.

I’m sure there are other aspects of how babies are made that were debated at the time. When I say debated, they were debated in scholarly circles, but the question of, for instance, resemblance mattered in cases of paternity. The question of paternity mattered enormously in terms of who was responsible for the financial well-being of the child or in terms of the disbursement of inheritance once the child had grown up. An inheritance was defined as taking on a whole set of characteristics, which could extend to the way somebody walked or their aptitude for a certain skill.

“Maternal imagination”

Resemblance was something that was debated for all sorts of reasons. There were famous cases where there were attempts to explain why a white woman might give birth to a Black child or why a blonde woman with a blonde husband might give birth to a child with black hair. These cases were often explained in terms of a notion of “maternal imagination”, which actually still has some purchase. It means that whilst the woman is pregnant, she is soft; she is impressionable. Women’s brains are always softer and moister than men’s, and their imagination is a faculty that is always susceptible to impressions. Literally, the way you press a stamp into wax, you could press an image or an idea into a woman’s imagination, and that could affect the infant that she was carrying.

Ensoulment and why it mattered

There are ridiculous pieces of advice that say if you’re going to have an affair, if you’re going to have sex with somebody who is not your husband, make sure you think about your husband so that the offspring that might ensue fits into the family. Obviously, this is kind of an intellectualisation, a way of articulating a world in which all sorts of things happened. The world has always been like this. There are the norms and the recognitions that they don’t always hold.

Tacuina sanitatis (XIV century), Ububchasym Baldach, (XIV-XV century). Biblioteca Casanatense, Rome, Italy. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Similarly, or not so similarly, the case of ensoulment mattered because there was a question, and this is a question that runs through the ages, about when a child was a child. There was an enormous theology that made arguments about whether it was at the moment of conception, whether it was the moment when the child quickened, which is the first time you feel the child move, or whether it happened even later than that.

These often played out around the Mediterranean, both in Islamic courts and in Christian courts, in cases of loss of life. If you injured a pregnant woman and she was simply injured, that was very different from injuring a pregnant woman and killing the child that she was carrying. The recompense, the punishment that was due, was different in each of these cases.

Progress or decline?

One of the things we’ve been able to do by pooling this expertise is to revise some of the long-term histories of the way in which histories of reproduction tend to be either stories of great progress or stories of great decline. Every once in a while, they’re stories of huge continuities, but the rise and decline stories are particularly interesting. Issues around women’s bodies and reproduction are fertile ground for all sorts of these histories, which are big stories about whether things get better or worse so that the stories of things getting better can centre on the history of medicalisation. One version of the history of medicalisation is that before modern medicine, all women died in childbirth. Obviously, not all women died in childbirth, but all women might have feared death in childbirth.

The medicalisation of childbirth

The medicalisation of childbirth is a story in which women are more likely to survive childbirth. It’s a story of great progress often set against a history of the medicalisation of childbirth as a bad thing in which women lost knowledge and control of their own childbirth processes.

A birth scene. Oil painting, circa 1800. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Another area where there has been this rise in decline stories is in the history of fertility. It’s often almost caricatured as a story in which, in the past, women had no control of their fertility and as soon as they had sex, they got pregnant and had far too many children. They therefore could never get themselves out of the home. That is not the early modern world as I know it – an era in which women are just subject to their reproductive bodies. They’re liberated from this with the advent of birth control and abortion, legalised abortion.

What this focus on the story of control, whether it’s controlling pregnancy through birth control or through abortion, what it stops us from understanding, because it is so much of our focus and it is so important to us, is how much infertility was a matter of concern in the past.

Discover more about

the history of reproduction

Hopwood, N., Flemming, R., & Kassell, L. (Eds.). (2018). Reproduction: Antiquity to the Present Day. Cambridge University Press.

Hopwood, N., Jones, P. M., Kassell, L., et al. (2015). Introduction: Communicating Reproduction. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 89(3), 379–404.