We come into a room together, and we trust that no one is going to pull out a gun and shoot us. We trust that the building we are in is not going to collapse. Trust is what happens when we run out of information, evidence and knowledge. Trust is a leap into the unknown, and it is when we become aware that we are trusting and needing to trust that it becomes more emotional territory, and it becomes about vulnerability, uncertainty and fear.

The emotional side of trust

Historian of Emotions

- Trust is often misunderstood as a purely rational process, but it is fundamentally emotional, involving vulnerability and uncertainty.

- Its meaning has evolved historically – from religious faith to interpersonal reliance – especially with the rise of modern urban life and complex societies.

- Cultural and gender norms shape how trust is built and expressed, with contrasting expectations for men and women and across different societies.

- In some cultures, like Korea, trust is cultivated not through evidence but through ongoing acts of care and mutual attentiveness.

Basis of trust

Trust is absolutely essential for our ability to cooperate with other people, to get anything done, to move around in the world at all. I think traditionally people define trust as a cognitive appraisal that we make about the world. We amass evidence that an individual or an organization or whatever is going to do the things it says it is going to do, and when we have amassed enough evidence, then we are able to trust them. We are able to expect that they are going to do the things they say they are going to do, and we are willing, therefore, to step back. We will not have oversight; we will not be checking everything they do; we allow them to get on with it. That is how we traditionally think about trust in this very behaviorist way.

© Pexels

An emotional response

What interests me about trust is its emotional aspects. We live in a world that is so complex that it cannot really be understood purely rationally. We cannot make rational assessments of everything that we have to trust. When we think about what trust feels like as an emotion, trust feels quite dangerous. I think it feels very vulnerable, and it feels exposing. The thing that is interesting about trust is that we do not notice trust most of the time.

© Pexels

I think the greatest misconception about trust is that it is a rational cognitive appraisal of a situation. The reality of trust is that it is a deeply emotional response. Some of those emotions are quite uncomfortable ones – it can feel very anxious, vulnerable and nerve-racking to trust someone. Understanding that is very important.

Trusting God or people?

The historian Ute Frevert argues that the meaning and definition of trust changed between the 18th and 19th century. In the 18th century, if you looked up trust in an encyclopaedia, what you would find is people talking about trusting in God. That was the context in which the word trust was used.

© Pexels

© Pexels

By the 19th century, as cities expanded, as people were encountering a lot more strangers, as industrial processes were beginning to fragment, in order to make something, you had to rely on people from all different kinds of businesses and backgrounds. They stopped talking about trusting God, and they started talking about trusting people. That is a very significant transition. It makes us really aware of this twin history of trust and the city. As people are living in these very overcrowded and busy cities, and as they are encountering a lot of people from different backgrounds, different cultures and different walks of life, where people might not necessarily be easily held to account, people can't necessarily be relied on to do the things they say they are going to do. This is where trust becomes necessary.

Communities vs big cities

A very famous study described the life of a French man called Bodo, who was a serf, and he lived in the 10th century in a small village outside Paris. Everything that Bodo consumed, ate, touched or used had been produced by just 80 people – all of whom knew each other, and Bodo knew all of those people.

© Im Kinsky Auktionshaus via Wikimedia

© Im Kinsky Auktionshaus via Wikimedia

In that kind of situation, where if anyone broke the rules, they would be punished, sent out of the network, as it were (they might be ejected from the village). In that kind of setup, trust is not exactly the same as the kind of trust that you might need if you live in a very big city where you are encountering people, perhaps only for a very short period of time. You do not have a lot of history together, and it is not obvious how those people will be punished if they break the rules. This is where trust really comes into play: in these moments of disparate, highly transient and mobile populations.

Trust across cultures

Trust is not this atmosphere that we wade into. It is not even something that we instinctively have for other people. Trust is something that we have to build, and we have to build it together. Of course, the ways in which we build trust have differed across time and certainly do differ across different cultures.

This is a very important topic for international, multinational businesses to grapple with: how do we build trust in different contexts with people whose ideas and expectations of how a trusting relationship develops may be dramatically different? Western theorists tend to talk about trust in terms of building evidence. We build evidence that someone is going to do the thing they say they are going to do, and that, over time, allows us to feel a sense that we can rely on them, and we can take them at their word.

Distrust in the workplace

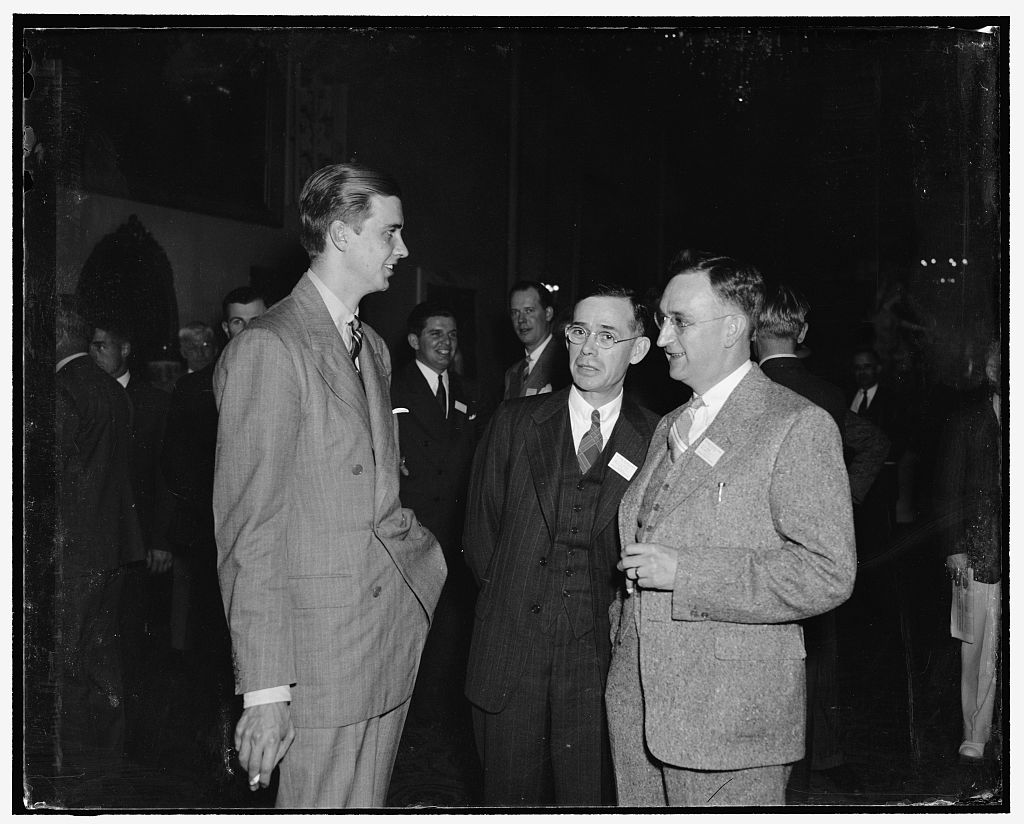

One example that springs to mind is the new generation of young women who were entering the workplace in the 1930s in America. In 1936, a businesswoman named Elizabeth MacGibbon wrote a book called "Manners in Business", which hit the best sellers list.

© Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress

© Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress

American offices saw themselves as very glamorous places where people from all over the country would congregate, and you would be meeting people from very different backgrounds, very different worlds to your own. Because of this, Elizabeth MacGibbon really cautioned the young women against making any friendships and trusting the other women they work with too closely. She said that there was a real danger in trusting your female colleagues, because they might gossip about you, or they might lure you into some sort of clique. They might undermine you in some way.

Messages of trust

MacGibbon's book was on the best-seller list in 1936, and the other book that was on the bestseller list in 1936 was Dale Carnegie's "How to Win Friends and Influence People", which is still on the bestseller list today. In that book – which is mainly directed towards male salesmen – Carnegie really emphasizes the importance of trust and of developing friendships and rapport with people that you work with, to the extent of remembering their birthdays, celebrating their children's anniversaries and so forth.

© Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress

© Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress

There is a stark difference in the kind of advice given to women and the kind of advice given to men. The idea that while men might benefit from the social capital that trust enables – expanded networks, a sense of reciprocity, the idea that favors could be done in mutual back scratching and so on – women were really encouraged to be very wary of one another and therefore to not be able to build up those kinds of networks.

I think we live in a world where we are encouraged to be open and trusting and trustworthy, of course, but the truth is that trust is experienced differently for different people in different kinds of circumstances.

Crisis of trust

The recent World Happiness Report suggested that there has been a dramatic dip in trust even in the last few years since the pandemic. It is very hard to know exactly what we mean when we talk about that.

© Pexels

© Pexels

It is not the first time people have spoken about living in a crisis of trust, but the idea that we might be living in such an age might really be evidence of a kind of hankering after a time where trust is not necessary – where everyone is compliant, where people are always well-meaning and have your best interests at heart, where trust is never broken; however, that is not the world we live in, and I think trust always is going to feel like a challenging emotion.

Mutual benevolence

Anthropologists looking at trust – different kinds of trust cultures – point out that this idea of evidence is not universal. One description that I have personally found very fascinating was a description of building trust in Korea. The anthropologists described a Korean concept called ma-eum. Ma-eum is an atmosphere of mutual benevolence and care, and the Koreans say you give ma-eum and you take ma-eum. Trust is built off the exchange, so the giving and the receiving of small acts of care. An act of care might be a physical gift or a present of some kind, or it might be a gesture that shows that you are thinking about someone, or you have concern for their well-being. It might be something as small as opening the door for someone or as large as showing up when they have a family emergency.

© Pexels

© Pexels

Over time, by giving and receiving these acts of care, you can create this atmosphere of ma-eum – that we-ness, togetherness – that then allows for a trusting relationship to flourish. It is quite different from the perception that we gather information and evidence about someone's behavior and then make a rational assessment of whether or not we trust them. This idea is that trust is something that we develop over a long period of time through sensitively feeling that the other person has our interests at heart and cares about us. It is a very different kind of approach to the idea of trust, and it is very important that we understand those differences.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

trust through friendship

Watt Smith, T. (2025). Bad friend: How Women Revolutionized Modern Friendship. Faber

Watt Smith, T. (2016). The book of human emotions: An encyclopedia of feeling from anger to wanderlust. Wellcome Collection.

Watt Smith, T. (2019). Schadenfreude: Why We Feel Better When Bad Things Happen to Other People. Wellcome Collection, Profile Books.

Edna Power, E. (2000). The Peasant Bodo: Life on a Country Estate in the Time of Charlemagne in Medieval People. Courier Corporation.

MacGibbon, E. (1936). Manners in business. Macmillan.

The Wellbeing Research Centre (2025). World happiness Report. University of Oxford.