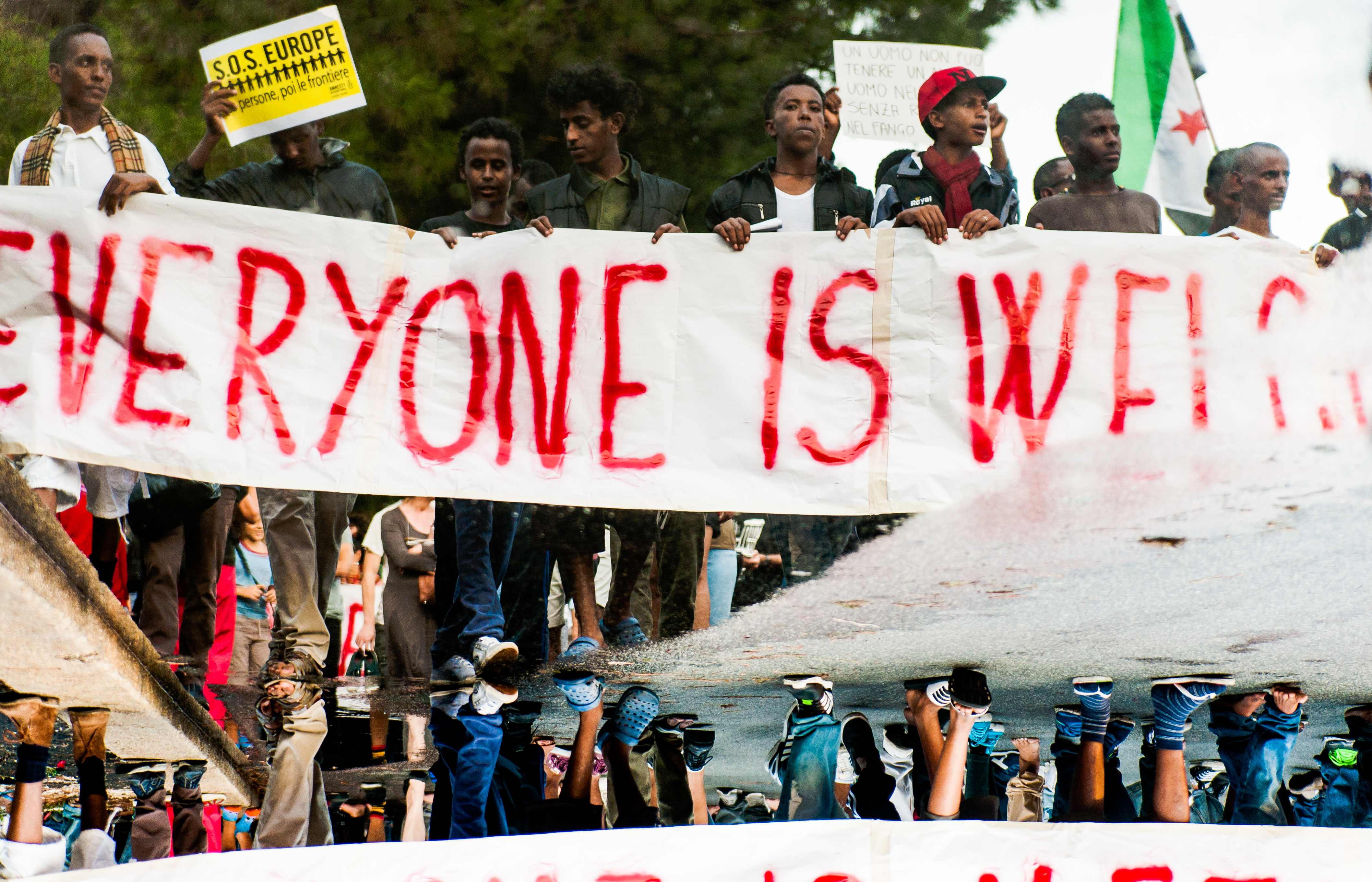

Over 70 million people today are displaced. This is roughly the size of the population of the 21st largest country in the world. I think it’s larger than Great Britain. Over 70 million displaced people, for me, are people who don’t have a nation, but they are people of a country that is entirely germane to the current situation that we are in. These 70 million people also represent the long history of the production of minorities, displaced people, with every turn in the large historical frame.

Now, if there are 70 million displaced people in the world today, every citizen has to recognise that she or he has a shadow – and that shadow is a displaced person. It could also be an undocumented person. It could be the person who comes and works in your garden or works on your house in America, who is undocumented and yet part of your own social fabric and allows you, supports you, to be a citizen.