It led me to move beyond conventional sources into images, paintings, photographs,objects, artifacts, songs – songs are very important the moment we step beyond Europe – and, finally, literary texts. I have always tried to understand this texture of past experiences by putting these diverse kinds of material next to each other and letting the different sources even argue amongst themselves.

Rethinking history, war and empire

Professor of Modern Literature and Culture

- As a historian, recovering lived experience often means going beyond conventional archives to images, artifacts, songs and literature to reconstruct lives that left few written traces.

- What counts as an archive depends on the questions and lens applied, so imperial, postcolonial or queer readings can draw very different meanings from the same material.

- Nearly 1.5 million Indians were recruited by the British Army during WWI; their contribution has almost fallen into the no man’s land.

- Literature helps us understand the fullness of the past in all its messiness, its plurality and contradictions. Legacies of war and empire are often contradictory and continue to haunt us.

The experience of the past

How does one understand and recover the experience of the past, particularly the texture of human experience, when those people did not leave behind many historical footprints? I think some people were most interested in certain topics, such as, for example, the intimate history of the First World War, entire colonial dimensions of warfare, the involvement of 4 million people of color in the First World War or, more recently, the maritime world, the world of sailors. Now, these men were either non-literate or often couldn't write about their experiences. What do we do about that?

© Santanu Das, personal archives

Archives and interpretation

Exactly what had engaged me was the very question of what is an archive to begin with. Is it a noun or is it a verb, as in, to archive? Is it a will to imperial knowledge, or is it a testimony to silences? On the one hand, we often need to create our archives for subjects for which there are not conventional sources. Equally important are the questions we bring to the archive, because the other thing is: when does an archive become a war archive, or when does an archive become a queer archive? An imperial historian and a postcolonial or a queer critic may look at the same material but raise very different questions and tease out very different intensities of meaning by looking at objects and images.

Different archival questions

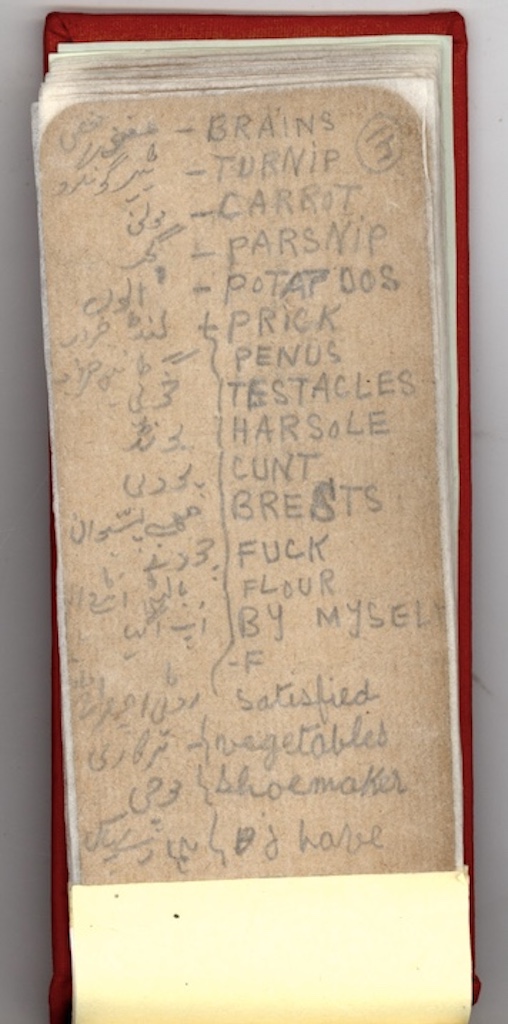

I had come across the name of Mir Mast because he was famous for deserting the British Army. He was part of the British Army and moved to the German side in 1915. In the archives in Delhi, suddenly I came across his strange notebook, and it was on an envelope that was sealed and confiscated. After almost a hundred years, I was allowed to break the seal, and out came this little trench notebook. Here you have a page from that book. This is one of the biggest reality checks for the post-colonial critic. It is full of rude words, body parts, as you can see: prick, penis, testicles.

Page from trench notebook of Mir Mast © Santanu Das, personal archives.

Suddenly you realize these things were what young people were thinking about. Now, for an imperial historian, it would be part of a larger narrative of this man who had moved, deserted and gone to the other side, and this is maybe not of much importance for a cultural historian. For a historian who is interested in intimacy, this is absolutely vital. When one is surrounded by death, it is almost a poignant testimony to appetite in its different forms. For example, on the same page he mentions parsnip, potatoes, and then prick, testicle – both for food and for bodies to come together. It is also the way an imperial historian and a post-colonial critic would look at a particular object. Often for historians, it would be part of a larger narrative, whereas a literary critic would investigate that and turn it around and around in their mind and tease out the different dimensions. Someone called my process one of archival hesitation – what does that mean? In a way, the narrative stops as I look at particular archival materials.

Literature beyond archives

I still believe that literature does help to fill in the gaps in the archives, but it also does much more and also slightly differently. For example, when I was looking at the whole role of India in the First World War, we have only fragments, little bits and pieces. We have this wonderful novel, Across the Black Water, written by Mulk Raj Anand much later, but his father was in the British Army, and though he did not fight, Mulk Raj Anand had contact with lots of people who did. It traces the journey of this village boy who goes to France, goes to the trenches, experiences the shock of the encounter with industrial modernity, a first visit to the brothel, then there is a suicide. It brings along the texture of experience which is missing in the archive. At the same time, there are other kinds of literature, and more commonly it comes in sideways and on tip toe and sets up its mirrors at strange angles. I will just give you one example, a little poem. It is one of my favorite poems, by the British poet Edward Thomas, and it is In Memoriam, Easter 1915. I will just read it out. It is about life on the home front: “The flowers left thick at nightfall in the wood. This Eastertide call into mind the men, now far from home, who with their sweethearts should have gathered these and will do never again.” Its flowers, Edward Thomas says, these flowers, and it brings to his mind these absent hands, these absent men who are all in France. This is something we would never find in an archive.

What literature helps us to understand is the fullness of the past in all its messiness, its incorrigible plurality and all its contradictions. At the same time, we often need to read them alongside historical archival material to bring in that touch of the real, whatever that might be.

“A Passage to India”

A good example is something like E.M. Forster's A Passage to India, started before the war during his first visit or shortly after his first visit to India, and then completed after the First World War and after his second visit. There is a tremendous difference in mood. What is interesting about A Passage to India is that the war does not really figure there; it is about the friendship between Aziz and Fielding. Suddenly, in the middle of it, we have Adela Quested, and then enter the whole Marabar caves. I became so obsessed with the novel that I even made the journey to Marabar Caves. In the caves, you have this strange echo. Is it that, after the First World War, the whole Forsterian cult of liberal humanism could only speak to the garbled version of boom boom like that? Is this meaninglessness and beyond the echo? Can one even hear the distant rattle of the guns of the Western Front, and even beyond it that of the Sepoy Mutiny?

E. M. Forster started the novel before the First World War, but then he ended it after the Amritsar massacre of 1919, when the relationship between the British and the Indians broke down completely. There is a lot of disillusionment after the war and after Amritsar, 1919, and this is the closing scene of the novel.

“Down with the English anyhow, that's certain. Clear out, you fellows, double quick. I say we may hate one another,” – and this is Hindus and Muslims – “we may hate one another, but we hate you most. If I don't make you go, Ahmed will. Karim will. If it’s 50 or 500 years, we shall get rid of you. Yes, we shall drive every blasted Englishman into the sea.” He wrote against him furiously, and then he concluded, half kissing him. “You and I shall be friends. Why can't we be friends now? Said the other, holding him affectionately. It's what I want. It's what you want. But the horses didn't want it. They swerved apart. The earth didn't want it sending up rocks through which riders must pass, single file. The temples, the tank, the jail, the palace, the birds, the carrion, the guest house that came into view. They didn't want it. They said in their hundred voices. No. Not yet. And the sky said, no, not there.” We have this tremendous sense of parting, but in a way, there are so many histories pulsing underneath it.

War and empire

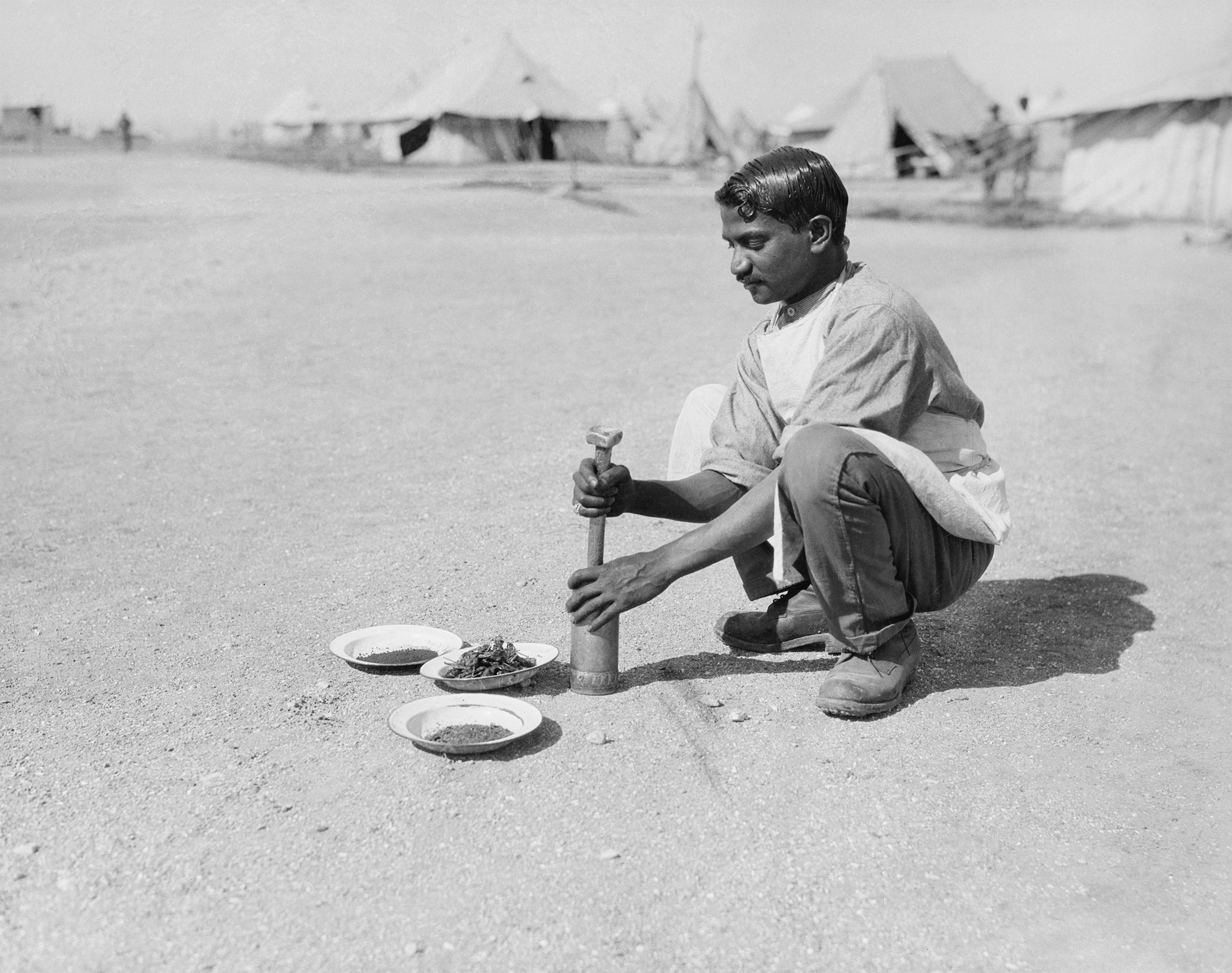

Indian Soldier paying homage © Santanu Das, personal archives.

Around 4 million men of color were recruited into the European and American armies, and of them, almost 1.5 million Indians. When I say Indians, I mean people from what was undivided India then and now includes South Asia. So, it is Bangladesh, Pakistan, India and Myanmar. There were 1.5 million Indians, including 900,000 combatants and 600,000 non-combatants. I wanted to recover their experiences. In a way, we use the words hidden history, and it is hidden in two ways. First, their contribution was not known. They had fallen almost into no man's land between the European or Eurocentric histories of the war on one hand and the nationalist histories in India or Pakistan on the other. They were also hidden because I wanted to recover an experiential or rather intimate history, not sealed in monuments and medals but about the everyday.

Broken, blood-stained glasses

I was on holiday in India, and I happened to visit the Dupleix museum in Chandernagore, which was the former French colony within West Bengal, where I came across this broken pair of glasses.

Jogendra Sen broken glasses © Santanu Das, personal archives.

The label said blood-stained, and it said it belonged to Jogendra Sen, who was killed in May 1916. Then you suddenly find these glasses in Chandernagore in India. They had been shipped to his widowed mother. I started doing more research, and I realized that he was the only person of color in the Leeds Pals Battalion, and he was the most educated man in that battalion. He was never promoted beyond a private because of his skin color. Then there were other little things, like a dog tag picture of a woman and other objects found on his body – but it is the glasses that even today almost haunt me, that these glasses would be shipped back all the way.

Indian soldiers in WWI

In the early stages of the war, in September 1914, the Indians were initially supposed to fight in Egypt, but because of the terrible losses on the Western Front, there was a decision made to allow the Indians to fight against other white races for the first time. Even within the hierarchy, there are different gradations of racism. Only Indians were allowed to fight in the Western Front, and it was largely Indians who held the line, at least one third of the line in the winter of 1914. Of course, there were hierarchies and racism; Indians were never allowed to become officers. There was often a lot of very good feeling and care between the British officers and the Indians. I have been working on this for almost 15 years. I have come across lots of examples and accounts, very moving accounts, of Indian sepoys saving the life of their white officers or bringing white officers from the battlefield to the dugout. Very sadly, I have not come across a single example of a white officer ever risking his life to save an Indian sepoy.

“Don't come, don't come”

When India entered the war in August 1914 through British decision, there was actually widespread enthusiasm from the princes of India from the different political parties. For most of the men in the Indian Army, soldiering was their source of livelihood. Many Indians were recruited. They volunteered; it was for financial need. We should never ever forget that. Once the first batch of Indians reached the trenches and realized the horrors of warfare, they would often write in coded form. I remember this letter which said, “Don't come, don't come, don't come to the war in Europe”. Later on, as the war progressed and as the recruitment levels dropped, there was forced recruitment, particularly in 1917 and 1918. For example, water would be cut off to the farmlands unless a particular number of men would volunteer from the villages. I came across this phrase when I was doing research in India: compulsory voluntary recruitment. In a way, that sums it up. Of course, there were some men who volunteered. There was a sense of honor and loyalty, but there was also this sharp economic need for the majority of Indian soldiers. It was their profession, a source of livelihood.

Mall Singh's voice

One of the most extraordinary discoveries in the history of war in recent years was these audio recordings, which were done between 1915 and 1918 by the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission. It was a commission formed of ethnographers, linguists, anthropologists, and they would go and record voices. We have more than 2,000 recordings, of which around 300 are of South Asian prisoners of war.

The Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission © Santanu Das, personal archives.

The one that is perhaps most remarkable is that of Mall Singh. Usually, the men were made to read a poem if they were literate, or sing a song or tell a story. What Mall Singh does is basically completely subvert that and tell his own life story. It is one of the most moving records, where he refers to himself in the third person, and he says, there was a man in India who came to the war in Europe. He goes on to say that he misses the taste of the ghee or butter he used to have back in Punjab, and if he is allowed back, he can again have the same food. Suddenly you realize the sense of tremendous longing and loneliness, and home is being remembered on the palate as taste. I keep on wondering, would he ever know that his voice, done in this most horrendous of circumstances, in this prisoner of war camp in Wunsdorf, would ever reach us a hundred years later?

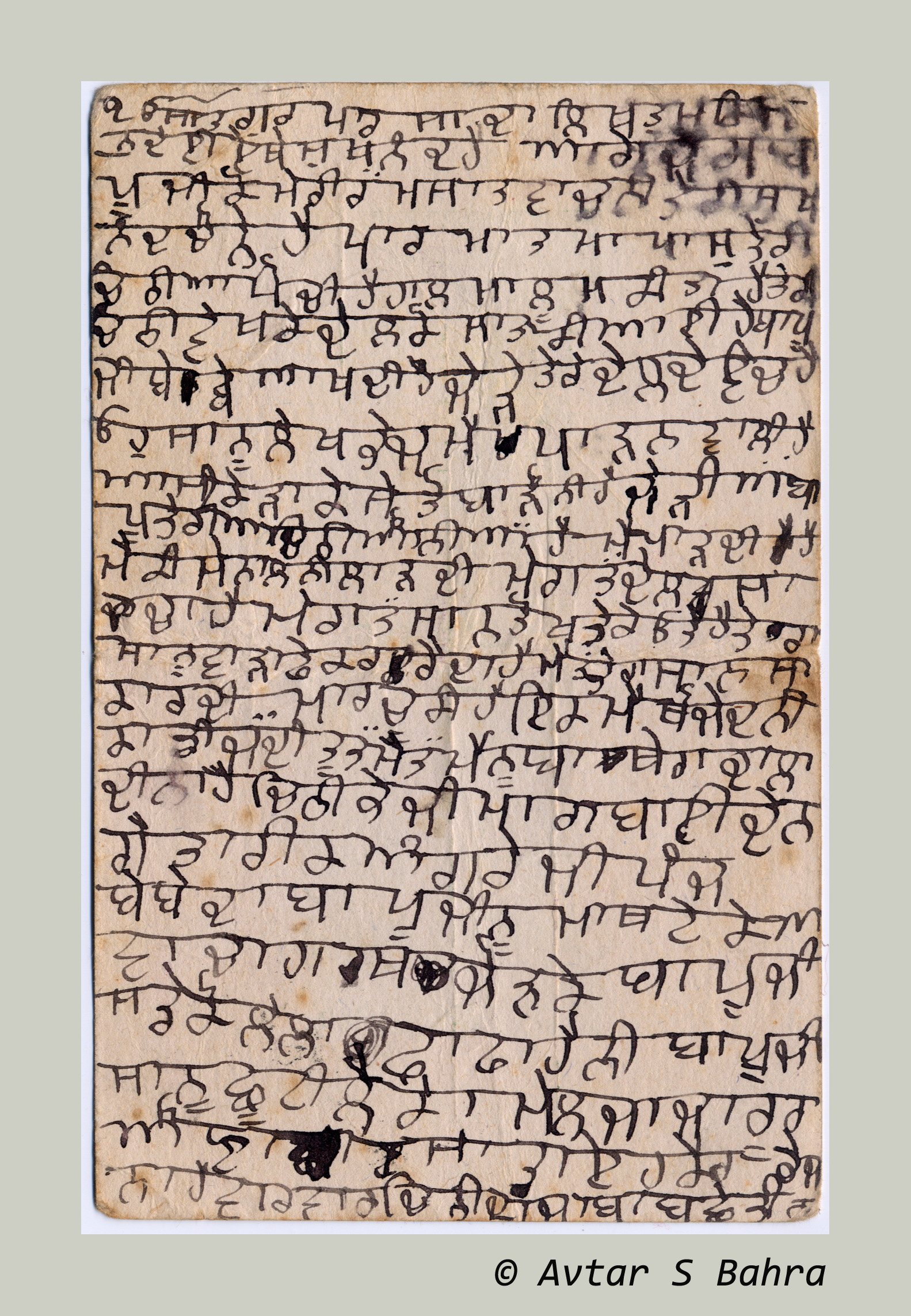

Letter from a young girl

A very rare letter that has been unearthed in recent years about the whole Indian experience, about the First World War, is via this young girl, I think maybe 10 or 12 years old from Punjab, writing in Gurumukhi to her father serving in Egypt. I’ll just read it out loud. You can see the letter and its child's hand, where she has joined all the letters.

Letter by young girl in Punjab to her father serving in Egypt © Avtar S. Bahra (Santanu Das, personal archives).

I will just read out a few sentences in translation. “We came to know about you. We were really scared after receiving your letter. Mother says that you can write to us about what goes on in your heart. Father, I shall read all your letters. My heart is yours. You are everything to me. And I worry about you. I'm like living dead without you. Dear father, please take leave and come and meet us. Please do come.” Suddenly, reading this letter, you realize that this young girl is learning how to read and write in order to read the letters, so that she can read out her father's letter to the mother, who is illiterate. Suddenly, the war front in Egypt and the home front in Punjab come very close. You realize some of these oblique effects of the war, that this education in Punjab is happening because of the participation of this Indian man in Egypt. It is rare, because I do not think there is any other artifact we have of someone so young, writing so movingly.

Family belongings

It is only after I started working on India in the First World War that I realized there were members in my own family involved. They had not been mentioned before, including one of my great uncles, Mahendranath Dass, who served as a doctor in Mesopotamia. He even got the Military Cross. Then out of the family wardrobe came his uniform medals. This is almost a metaphor of how memory functions, because it is there, but it is subterranean, buried under the nationalist layers. I keep on saying amnesia does not mean absence. The memories are there, silently and privately, and we need time and we need to dig and dig.

Coming back home

There is a lot of enthusiasm within India for the war efforts, because the political leaders thought that they would use it after the war to bargain for greater political autonomy. When the soldiers came back, there was a huge sense of disappointment, because it was very soon followed by the massacre in Amritsar, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, where basically these peaceful protesters were herded into this garden and gunned down. In a way, that casts its shadow over the whole First World War experience, for example, Mahatma Gandhi, one of the pacifist icons of the 20th century. He was busy recruiting Indian soldiers in 1918, and the same man in 1919 called the Indian soldiers the hired assassins of the Raj. When the soldiers came back home, there was some financial compensation but not a memorial or structure of memory that we find in Europe. Often within the same family, there was this bitter divide. These histories are not uncommon. The memory of the Indian contribution gets largely overshadowed by the nationalist movement that really took off after the First World War.

Powerful encounters

Indian soldiers taking part in Bastille Day celebrations in Paris, 14 July 1916 © Excelsior via Wikimedia.

During 1914 and 1918, hundreds of thousands of Indians were sailing to the heart of whiteness and beyond Mesopotamia, East Africa, resulting in this dizzyingly wide variety of encounters – in battlefields, in hospitals, in boardrooms, in brothels and in markets. I will just give one example. This is a young Indian soldier in France who is billeted with an elderly French woman, whose three sons are away. I will just read out the letter.

This is a letter from Sher Bahadur Khan, written on the 9th of January, 1916, from France. He is writing about this elderly French woman with whom he had been billeting. I will read from the letter. “Of her own free will, she washed my clothes, arranged my bed and polished my boots. Every morning she used to prepare and give me a tray with bread, butter, milk and coffee. When we had to leave the village, the old lady wept on my shoulder. Strange that I had never, ever seen her weeping for her dead son, and yet she should weep for me. Moreover, at our parting, she pressed on me a five franc note to meet my expenses en route.” I think we need to think beyond these binaries of colonizer and colonized, because these are very powerful encounters where race, vulnerability, loneliness, affection, all of them, are fused and confused.

I came across exactly this passage in a text written by Kipling called Eyes of Asia, where he imagines himself to be an Indian soldier. I suddenly realized, and this is again in the British Library, that he had access to these letters, and he was reprinting them for propaganda purposes.

Both these aspects have to be acknowledged in order to understand these difficult, often contradictory legacies of war and empire, and the way they continue to haunt us, even today.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

history and empire

Das, S. (2018). India, Empire, and First World War Culture: Writings, Images and Songs. Cambridge University Press.

Das, S. (Ed.). (2011). Race, Empire and First World War Writing. Cambridge University Press.

Das, S. (Ed.). (2013). The Cambridge Companion to the Poetry of the First World War. Cambridge University Press.

Das, S. (2014). Indian Sepoy Experience in Europe, 1914–18: Archive, Language and Feeling. Twentieth Century British History, 25(3), 391–417.

Das, S. (2012). Sensing the Indian Sepoy in the First World War. Comparative Critical Studies, 9 (Supplement), 7–18.

Das, S. (2010). Ardour and Anxiety: Politics and Literature in the Indian Homefront. In Liebau, H. Bromber, K., Lange, K., Hamzah, D. & Ahuja, R. (Eds.), The World in World Wars: Experiences, Perceptions and Perspectives from Africa and Asia (pp. 341–368). Brill.

Anand, M.R. (1939). Across the Black Waters. South Asia Books.

Forster, E.M. (1924). A Passage to India. Penguin Classics.