Changes in the art of the period, in Renaissance art, the advent of the Renaissance nude in the work of people like Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raphael or Leonardo da Vinci, all of that work is embedded in this change in the understanding of the body.

A history of the body in the Renaissance

Cultural and Art Historian

- The Renaissance changed how people saw the naked body, viewing it as a sign of human potential and beauty rather than sin or shame.

- Artists and scientists collaborated through dissection and close observation, leading to new insights into anatomy and the human form.

- Renaissance medicine tied physical appearance to health, character and gender roles, influencing beauty standards in daily life.

- The ideal body in art was a made-up blend of features, often androgynous, and these imagined forms still shape how we see bodies today.

Reevaluation of the human body

The Renaissance is a period of massive change in many different ways, and that includes the way that the body is understood. Major changes include the advent of printing, voyages of exploration to other places and the revival of interest in classical literature and classical arts, all things to do with ancient Greece and Rome. That is why the Renaissance gets its name from the rebirth of those ideas. All of these together bring about a kind of reevaluation of the human body in terms of looking at the body and ideas of nakedness, and that is what I have been particularly interested in working on — the idea from medieval texts that the naked body is inherently shameful and that God made the body naked to make humans aware of their weakness and their frailty. That starts to change. People start to argue more that the reason why humans are naked is because of their potential.

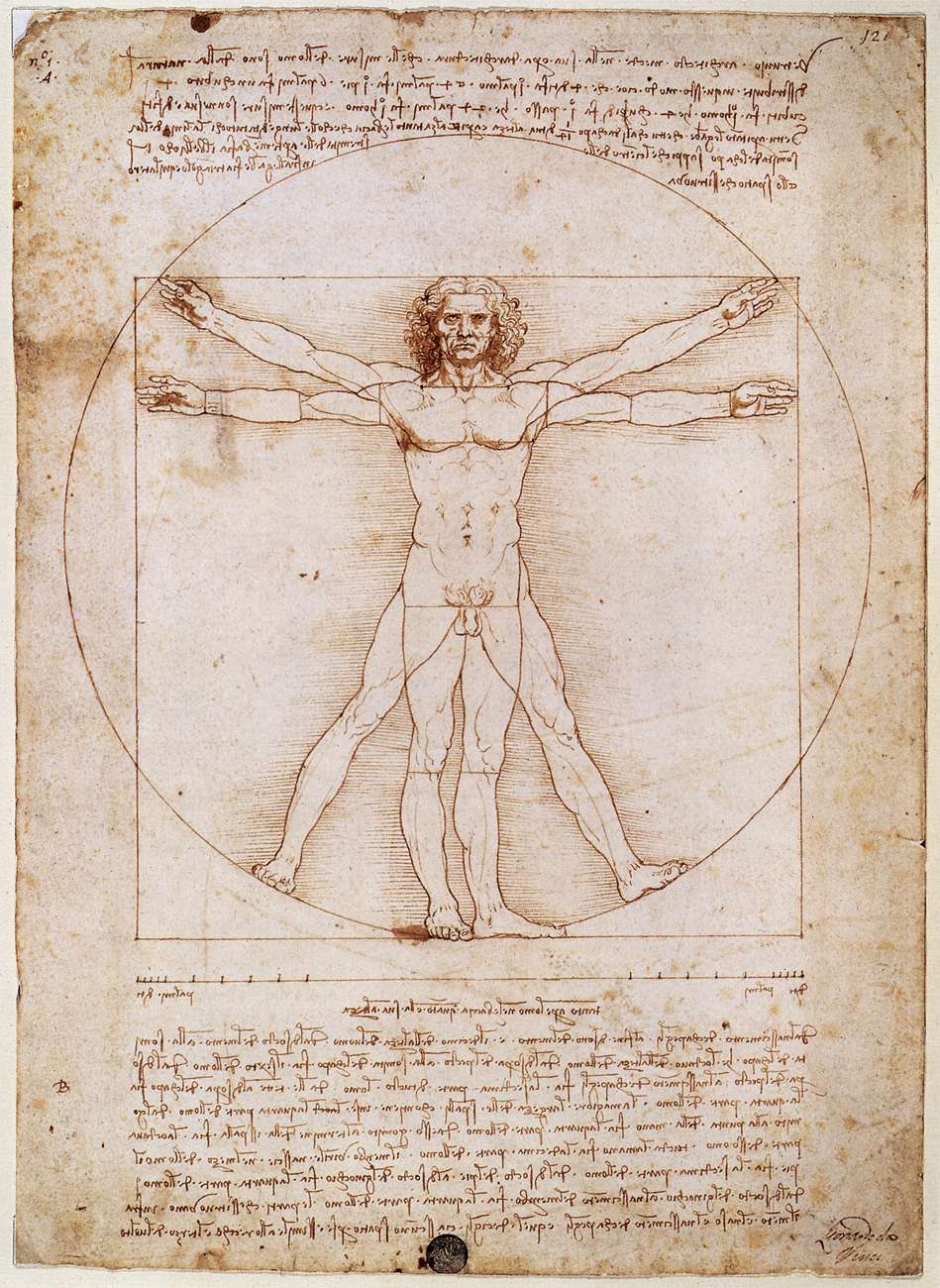

Vitruvian Man © Leonardo da Vinci, Gallerie dell'Accademia via Wikimedia

Vitruvian Man © Leonardo da Vinci, Gallerie dell'Accademia via Wikimedia

Adaptable to anything

Compared to animals that have fur, feathers or quills and that can only do one thing — so spiders, for example, can weave webs or birds can make nests and fly — humans, through their nakedness, can adapt to anything. They can make tools; they can use nature in order to dress their bodies, make medicine for their bodies and so on. They start with this argument that the naked body is not sinful but beautiful — that humans are made in the image of God.

The body under the skin

This reappraisal of nakedness — this understanding of the naked human body as something to be praised and something that is God’s handiwork — meant that discovery of the body under the skin, discovery of the body’s anatomy, also became something that was acceptable to look at. This also went hand in hand with a new emphasis in drawing and in what we now call the visual arts, in observing nature. So you'd get people like Leonardo da Vinci, for example, and some artists before him, like the Pollaiolo brothers, who would undertake dissections of bodies so that they understood how muscles would fit together. They understood the state of the bones and muscles below the skin.

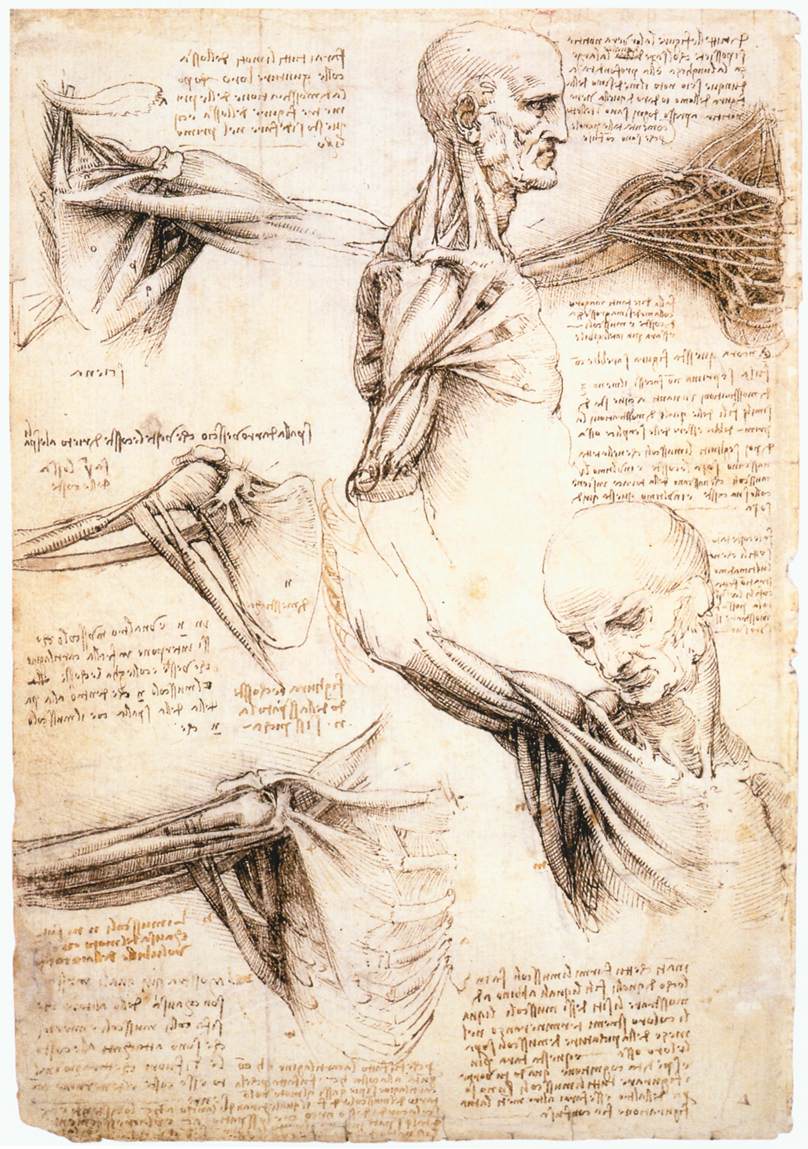

Anatomical studies of the shoulder © Leonardo da Vinci, Royal Library at Windsor Castle via Wikimedia

Anatomical studies of the shoulder © Leonardo da Vinci, Royal Library at Windsor Castle via Wikimedia

Leonardo particularly used new drawing techniques, new techniques of observation and the availability of paper, to really get to grips and understand the perfected human body — the body as God and they understood it and would have wanted bodies to look like, before the fall of Adam and Eve and their descent from Paradise. This reappraisal of the human body really had massive and long-lasting effects on things that you might not expect, like the study of anatomy and the scientific revolution.

Between science and art

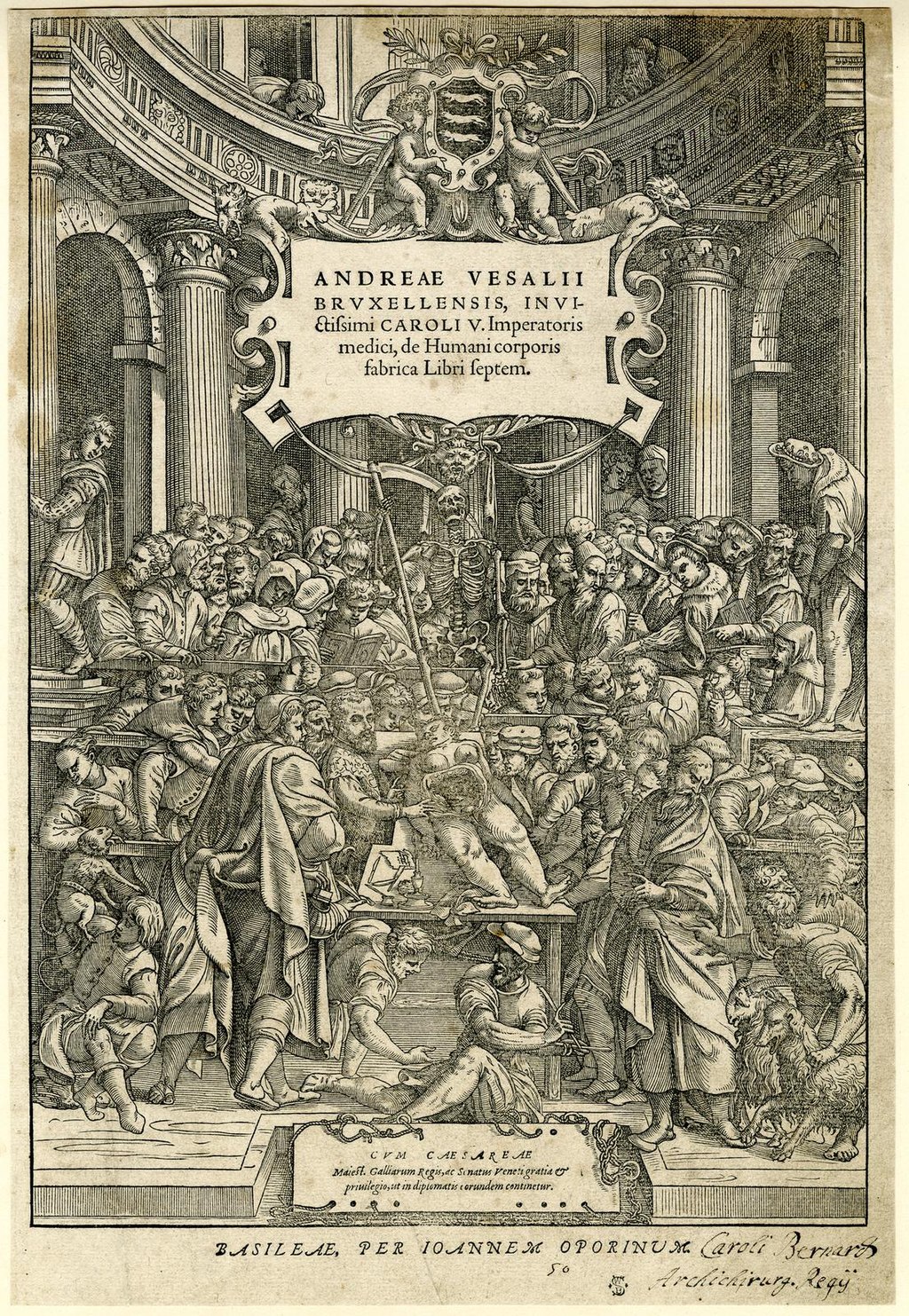

In the Renaissance, there is a continued tradition of understanding the body in relationship to the humoral system. There is also an understanding of the appearance of the body in new ways. The body and its interior is looked at in many different ways. Some of the landmarks include Vesalius’s book of anatomical images and studies, called "On the Fabric of the Human Body". This came out in 1543, included engravings by artists from Titian’s workshop and really dominated anatomy for the next century — particularly because of the quality and the amount of illustrations.

On the Fabric of the Human Body, Andreas Vesalius; Jan Stephan van Calcar, The Trustees of the British Museum via Wikimedia

On the Fabric of the Human Body, Andreas Vesalius; Jan Stephan van Calcar, The Trustees of the British Museum via Wikimedia

You can see this new interest and real popularity of understanding the human body in new institutional spaces, like the anatomy lecture theatres in Padua or Bologna, where they build anatomy theaters where you would have the cadaver and the teacher (the lecturer) at the bottom. The students would sit on steeply stepped seats so everyone could see what was going on. They would test what they can see — the evidence of the body, the evidence of looking — against the authority of classical texts, like Galen particularly. They would test his hypotheses through experiments, and that was a fundamentally new idea. The records of this experiment were recorded by Renaissance artists. The relationship between science and art was very, very close in this period.

Diagnosing personalities from the exterior

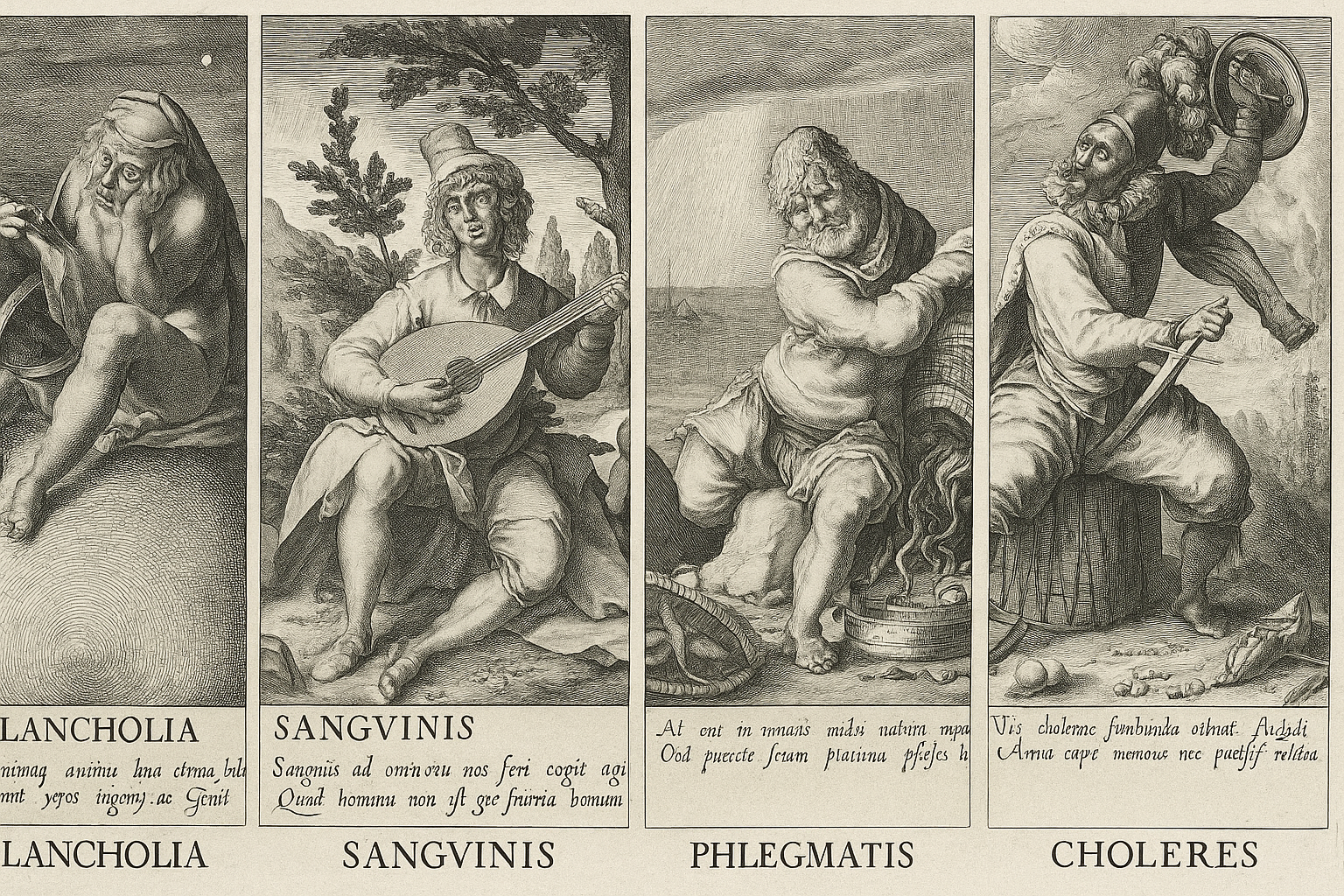

Renaissance medicine is still very based in the humoral system, which is a classical and antique system of understanding the body in relationship to its humors. The idea is that every body — all bodies, including animal bodies — are made up of four humors, and the balance of these humors is related to health but also to temperament, gender expression and appearance.

Les Quatre Complexions de l'Homme © Charles Le Brun, Palace of Versailles, R.M.N. via Wikimedia

Les Quatre Complexions de l'Homme © Charles Le Brun, Palace of Versailles, R.M.N. via Wikimedia

This is such a common way of understanding the body that in the 16th and 17th centuries, they would bring out handbooks of physiognomy that would tell you how to diagnose people’s personalities from the exterior of their bodies. This becomes really important when you look at, for example, advice to men on how to choose wives. Men are told to choose wives with golden, slightly wavy hair and white, peaches-and-cream skin and a slightly plump body; these women were thought to be particularly fertile but also to be obedient and clever enough to have clever children — and because they had the right balance of humors.

Similarly, women with dark, curly hair were said to be not a good match, because they were prone to being argumentative and were likely to be infertile, whereas women with very blonde hair were argued to be unintelligent and not good for giving birth to intelligent male children. There is this overlap of medicine and popular ideas of appearance that is really important for understanding the art and the culture of the period.

The rise of the nude

One of the things that has been well known about the Renaissance for a long time is the advent and the popularity of the nude form. In the Middle Ages, you get some naked figures — Adam and Eve is an obvious example — but you do not get repeated images of naked men and women. That only really starts in the 15th and 16th centuries. It used to be thought that this was somehow just related to copying after classical art. It is true that the new enthusiasm for the antique and for the work of ancient sculptors is very important.

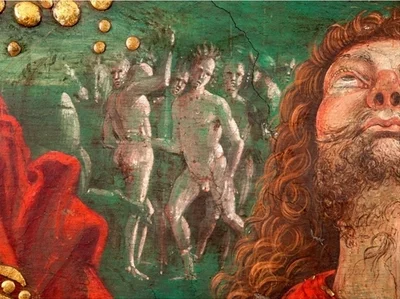

The Resurrection © Pinturicchio, Courtesy of Vatican Museums

However, other things happened in this period, too. For example, the voyages of exploration led to new understandings of people in sub-Saharan Africa, and in what was then called the New World and the islands, often described as "naked" by explorers. There is this new idea of nakedness as being related to a state of innocence and a state of lack of civilization, on the one hand; on the other hand, there is this idea that if artists can draw naked people, that is somehow people without the fashion that clothing and hairstyles, for example, or other kinds of trappings of everyday life.

It is argued that the nude form is a perfect body that is a product of the artist's mind. This goes hand in hand with the idea of the artist as this special category of person that can create beautiful things that are more beautiful than the things that you would find on Earth. The nude is part of that process by which art becomes separated out from just normal earthly things.

Controversies around nudity

The nude becomes a form that is very attractive to artists because it speaks to the essentials of humanity. There are many different things happening in this period that bring about the nude. Some people really reacted badly to this advent of the nude form, particularly images of naked women, which many people thought were absolutely scandalous — but naked men, too.

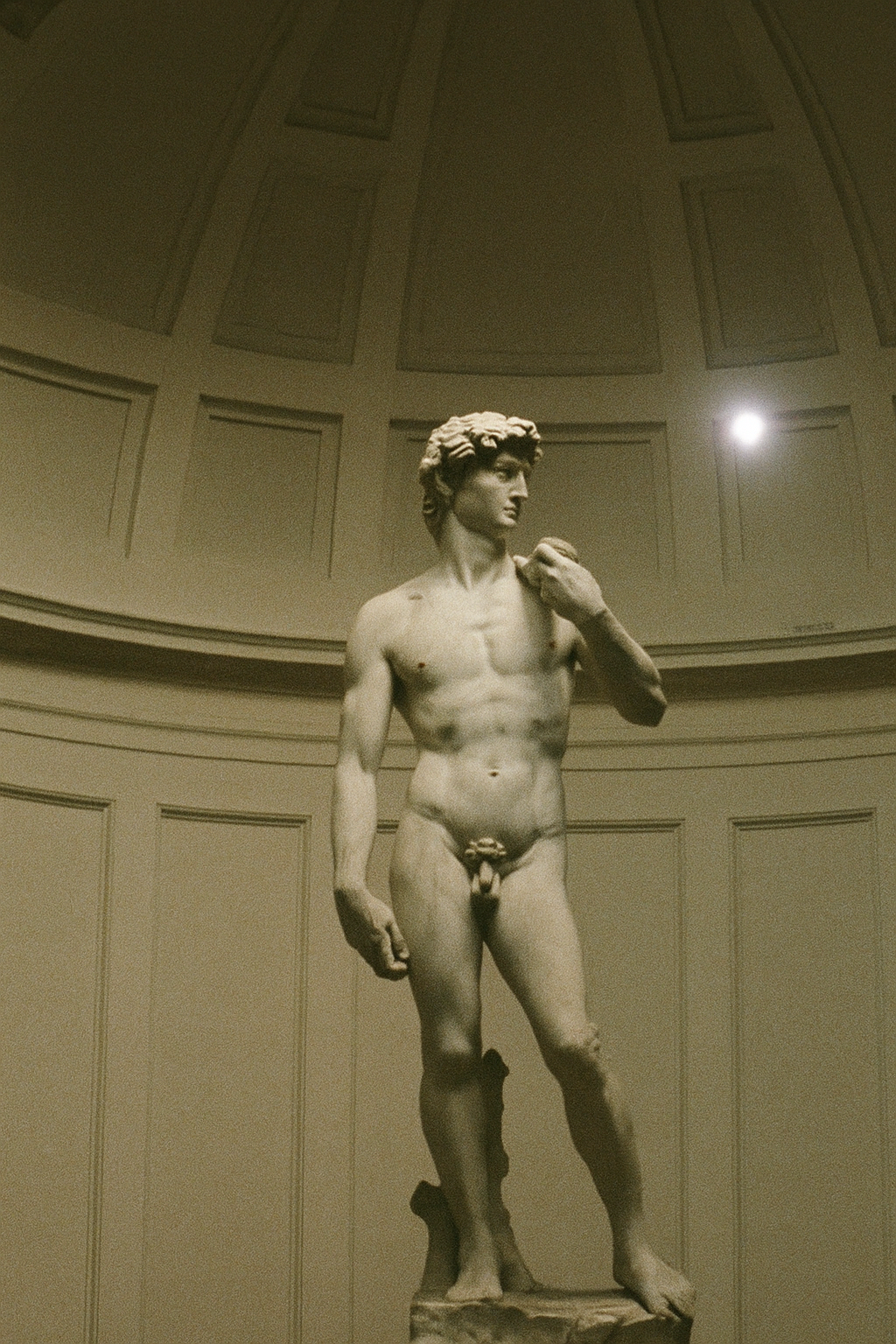

David © Michelangelo via Pexels

David © Michelangelo via Pexels

For example, Michelangelo's David, which everyone knows well — it is one of the most famous artworks of the Renaissance — when it was first displayed, it had a covering for its genitalia because people thought, and people understood, this might be shocking to those going about their business in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence. There was anxiety over nakedness in a way that was progressively forgotten in the centuries since then, because in real life it was very difficult, and people were very rarely seen naked, particularly women. Even in marriage they would keep their underclothes on. A proper, chaste woman would certainly never allow herself to be seen naked, even by her husband.

“Isabella Ruini”

The image of Isabella Ruini as Venus is a really fascinating painting. It is both because of Isabella Ruini being portrayed in a way that would not have been understood as socially acceptable — in that she is semi-naked — and also because it is a painting by Lavinia Fontana. It is really one of the first paintings by a woman artist of the female nude.

This painting was made for Ruini's husband and would almost certainly not have been on public display. It would have been something just for her and her husband and perhaps a few others — an intimate portrait.

Venus and Cupid © Lavinia Fontana, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen via Wikimedia

Venus and Cupid © Lavinia Fontana, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen via Wikimedia

The nude, more generally, howver, was expected to provoke desire. You often see nudes being shown in the context of bedchambers, for example, and they were understood to provoke desire in both men and women who looked at them. So this is an interesting idea of gender fluidity when it comes to the way that nudes evoke desire in this period.

Ruini’s portrait, in a way, is quite daring, but it also celebrates her beauty, because she was one of the most celebrated beauties in Bologna at the time. There is a lot going on here, related to what is licit, what’s illicit, how desire is regulated. Nudes were acceptable in some settings and not in others. The framing and placement, the original display of these nudes, was really important.

I think Isabella Ruini would have been totally shocked to know that it is now so easy to get an image of her semi-naked — you can get it on the internet — or that these kinds of images are now being shown in galleries. That would have been completely alien to her understanding of what this image was for.

Male and female bodies

In the 15th century, the ideal body was overwhelmingly understood to be a male body. If you look at early painters' manuals, like Cennino Cennini’s manual for painters, he gives a set of ideal measurements for the male body, and he says, just draw women from nature, because they do not have ideal bodies.

In artistic training, which really starts off with drawing after the nude in Florentine workshops in the later 15th century, people drew after naked male bodies again and again and again. There are many drawings that survive from this period. Sometimes you can see the same model being drawn from different poses by different people in a workshop, for example.

Bacchus © Leonardo da Vinci workshop, Musée du Louvre via Wikimedia

Bacchus © Leonardo da Vinci workshop, Musée du Louvre via Wikimedia

All through the period, right up until the 18th or 19th century, it is still much easier to get ahold of male models for this male-dominated field; there were not many female artists. As you get into the later 15th, and certainly into the 16th, century, people increasingly start to use female models as well, and they start to appreciate the female form — not necessarily as ideal but as beautiful.

They start to understand that maybe women’s bodies can be more beautiful than male bodies. This is an argument that starts to be made again and again in a type of pro-woman literature, where people start to say women’s bodies are very beautiful. You start to get evidence, too, of life drawing after the female nude — probably using servants and perhaps using sex workers (it is not certain); courtesans, certainly; women who would be willing to take their clothes off in return for some payment. This tended to happen not in the workshop but in private rooms.

There is a different understanding of the male and female bodies, but basically you see this increasing idea that although male bodies may be ideal, female bodies can also be beautiful. You see that increasingly into the 16th century.

The appeal of androgyny

When you look at the nude in the Renaissance, it is important to understand that the ideal nude is not meant to be based on a real body. It is meant to be based on a composite idea of lots of beautiful bodies. The advice that the artist might have been given was to take a beautiful arm from this figure, a beautiful leg from that figure and so on. There was an argument that the truly beautiful body could not exist in the world – it could only exist in the realm of the mind.

This is one of the reasons why androgyny — the idea that you could mix male and female to create a more beautiful body — becomes really popular in the early 16th century.

Saint John the Baptist © Leonardo da Vinci, Musée du Louvre via Wikimedia

Saint John the Baptist © Leonardo da Vinci, Musée du Louvre via Wikimedia

Michelangelo brought together both male and female characteristics in some of his female nudes, particularly, whereas Leonardo used feminine characteristics for male figures in order to create a body that was clearly not existing in the world. It was a body that, for them, was perfectly beautiful.

Ideal bodies a historicized idea

I think people often feel that their attitude and the way they feel in their own bodies is their own personal issue, that body dissatisfaction is something new, and it is something for which they can almost blame themselves. Whereas, in fact, the ideal body — the idea that people should have an ideal body, the idea that your own body is lacking in the face of an ideal — is a historicized idea.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

I relate the beginnings of that idea on a mass scale to the Renaissance. If you can provide some distance, and for people to understand that these feelings that seem so personal and intimate are actually operating in a historical place, in a certain place and time, because of large-scale historical forces, it can help disentangle a complex mass of ideas about selfhood and identity in the body and society. The history of the body can be really helpful to think about our attitudes towards our own bodies — and other people’s bodies, too.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

The Body in the Renaissance

Burke, J. (2024). How to be a Renaissance woman: The untold history of beauty & female creativity. Wellcome Collection.

Burke, J. (2018). The Italian Renaissance nude. Yale University Press.

Burke, J. (2013). Nakedness and Other Peoples: Rethinking the Italian Renaissance Nude. Art History Volume 36, Issue 4, Pages 714-739.