© Vittoriale Musei via Wikimedia

© Vittoriale Musei via Wikimedia

The secrets of Renaissance cosmetics

Cultural and Art Historian

- Cosmetic history is often told as a tale of vanity, overlooking the deeper cultural, social and medical contexts.

- Renaissance beauty recipes were part of a broader knowledge system, often overlapping with medicine, magic and everyday domestic practices.

- Women who made cosmetics were central figures in their communities and sometimes targeted as witches because of their expertise.

- Reconstructing recipes reveals how sophisticated and effective historical beauty practices could be, challenging assumptions about past knowledge.

History of cosmetics

The history of cosmetics has often been told as a series of eccentric things that women did, and really for vanity. You will often get extended histories of cosmetics that will start in ancient Egypt and end with industrialization or with the present day. They will really go from one unusual cosmetic recipe that might use strange ingredients or unpalatable ingredients to another, and what they will not often take into consideration is why people might want to use these ingredients. What are the stakes and how does that fit in with a broader culture of understanding of femininity and beauty?

© Sandro Boticcelli, Städel Museum via Wikimedia

© Sandro Boticcelli, Städel Museum via Wikimedia

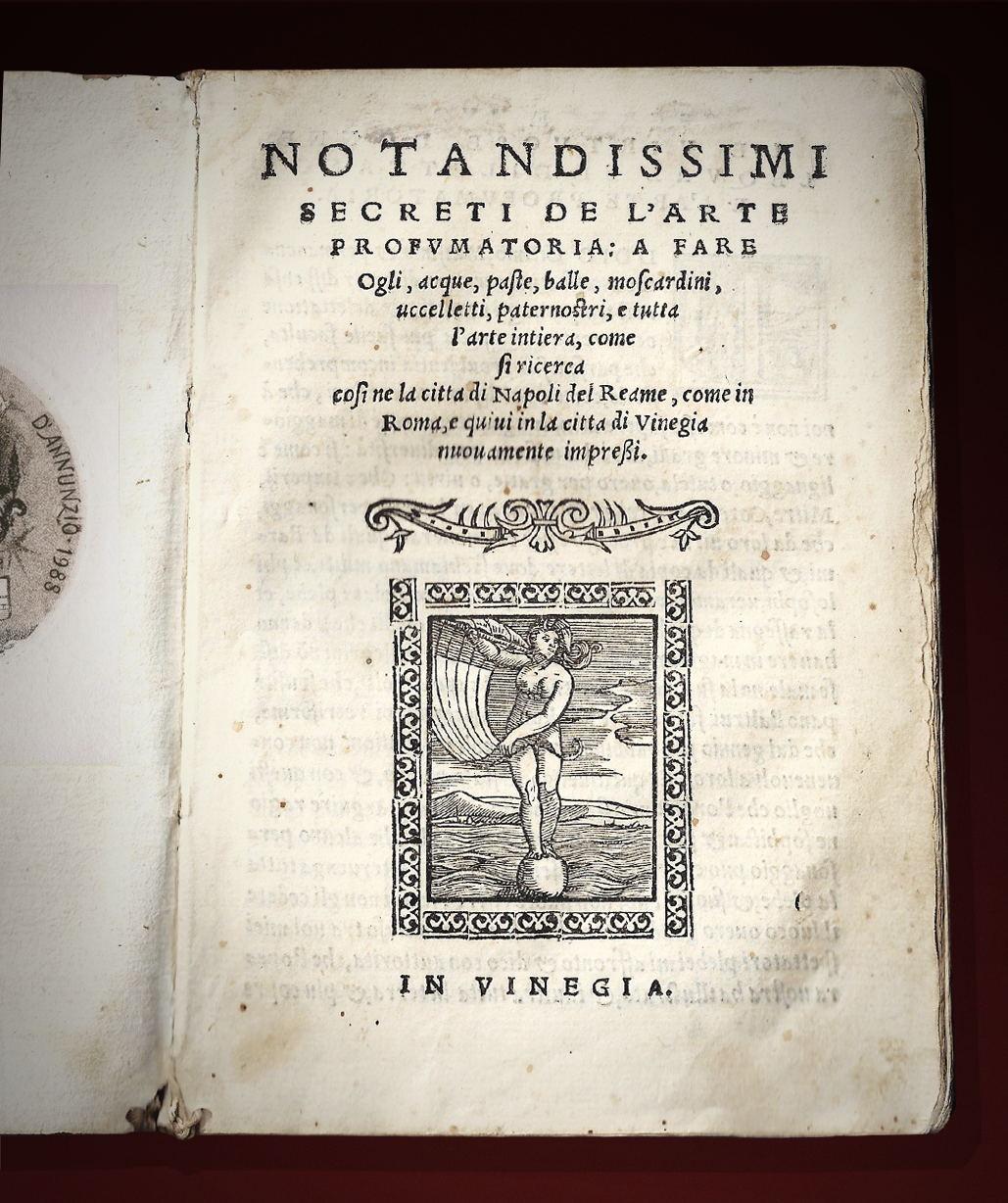

Books of secrets

Renaissance cosmetic manuals are a very exciting source, partly because they have been massively understudied and also because there is a significant amount of material. I am now working on Renaissance cosmetic manuals as a genre. There are many, many manuscript sources from the 15th through the 17th century where cosmetic recipes are written down. Sometimes cosmetic recipes form parts of wider books of recipes that might be also for cooking, for example, or for medicines, and there are also many printed books.

Cosmetics forms an important part of what were known as books of secrets. Books of secrets are recipes for all sorts of household medicine, cleansing products, hygiene products and so on, and cosmetics often formed part of that. Although we have known about these books for a very long time, they have a long history of people studying them; they are quite difficult to understand unless you look at the individual recipes quite closely. A book of secrets might typically have hundreds and hundreds of recipes in them. It used to be that people just studied the books without looking at the recipes, but now there is more and more attention to the recipes themselves and the reconstruction of these recipes. This reveals a whole world of knowledge and understanding of which we were previously not really aware.

Blurred lines between cosmetics and medicine

One of the interesting things about these books of recipes is where cosmetics appears. Sometimes you get handbooks that are designed for women that just have cosmetic recipes in them, but also where cosmetics end and medicine starts is really difficult to know. A lot of medicine, for example, for getting rid of parasites like scabies or that treats rashes also has a cosmetic effect. This was the case even more so in the period when it was believed that if you changed the interior humors of your body, if you were healthy, you would then be more beautiful.

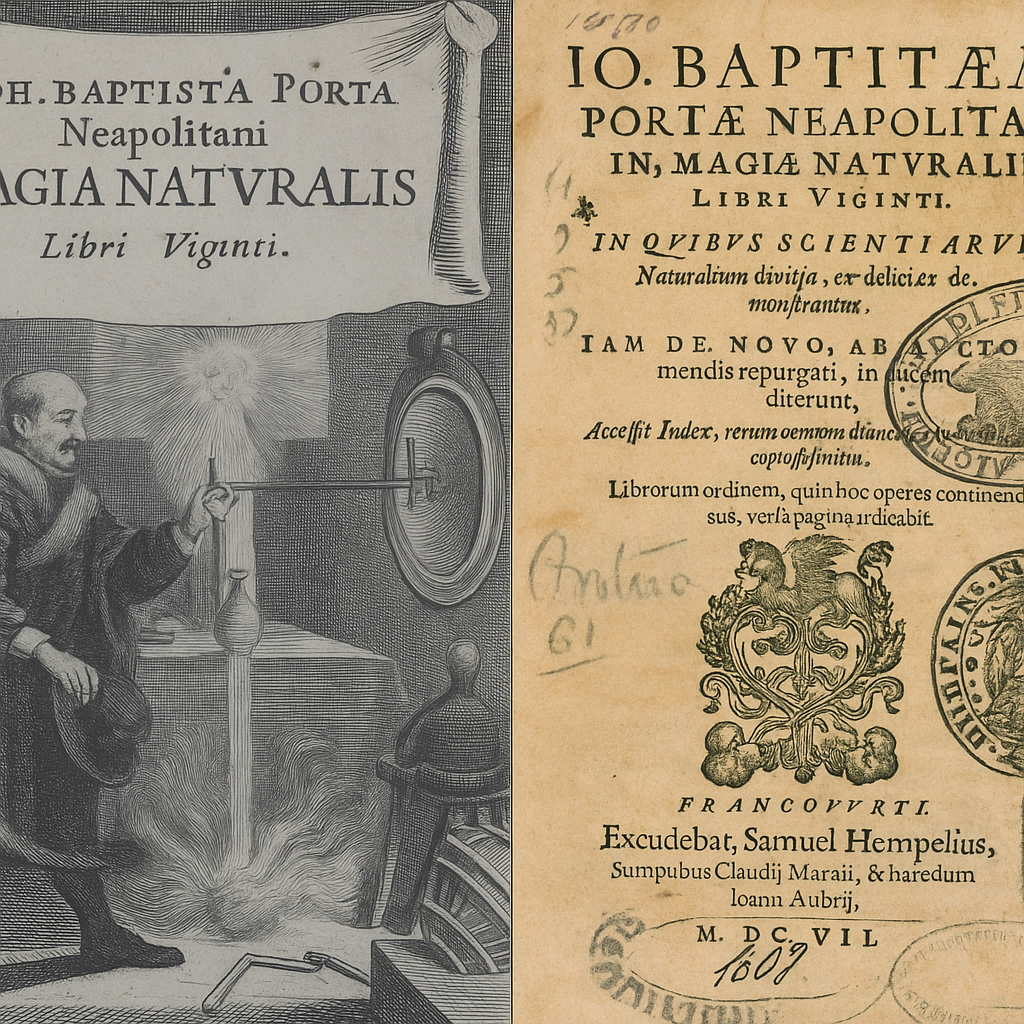

© Magia naturalis by Giovanni Battista della Porta, Nationale bibliotheek van Nederland via Wikimedia

© Magia naturalis by Giovanni Battista della Porta, Nationale bibliotheek van Nederland via Wikimedia

There is a writer called Giovanni Battista de la Porta, who writes a book called "Natural Magic" in the late 16th century, and he includes cosmetics as part of that book, because it is about manipulating nature. It is extracting qualities from natural products, plants and animals and applying it to the human body to change that body. Cosmetics sits between magic, medicine and beauty, and a lot of alchemists also make makeup because distilled waters, for example, which involve equipment like alembics, were very commonly used in cosmetics.

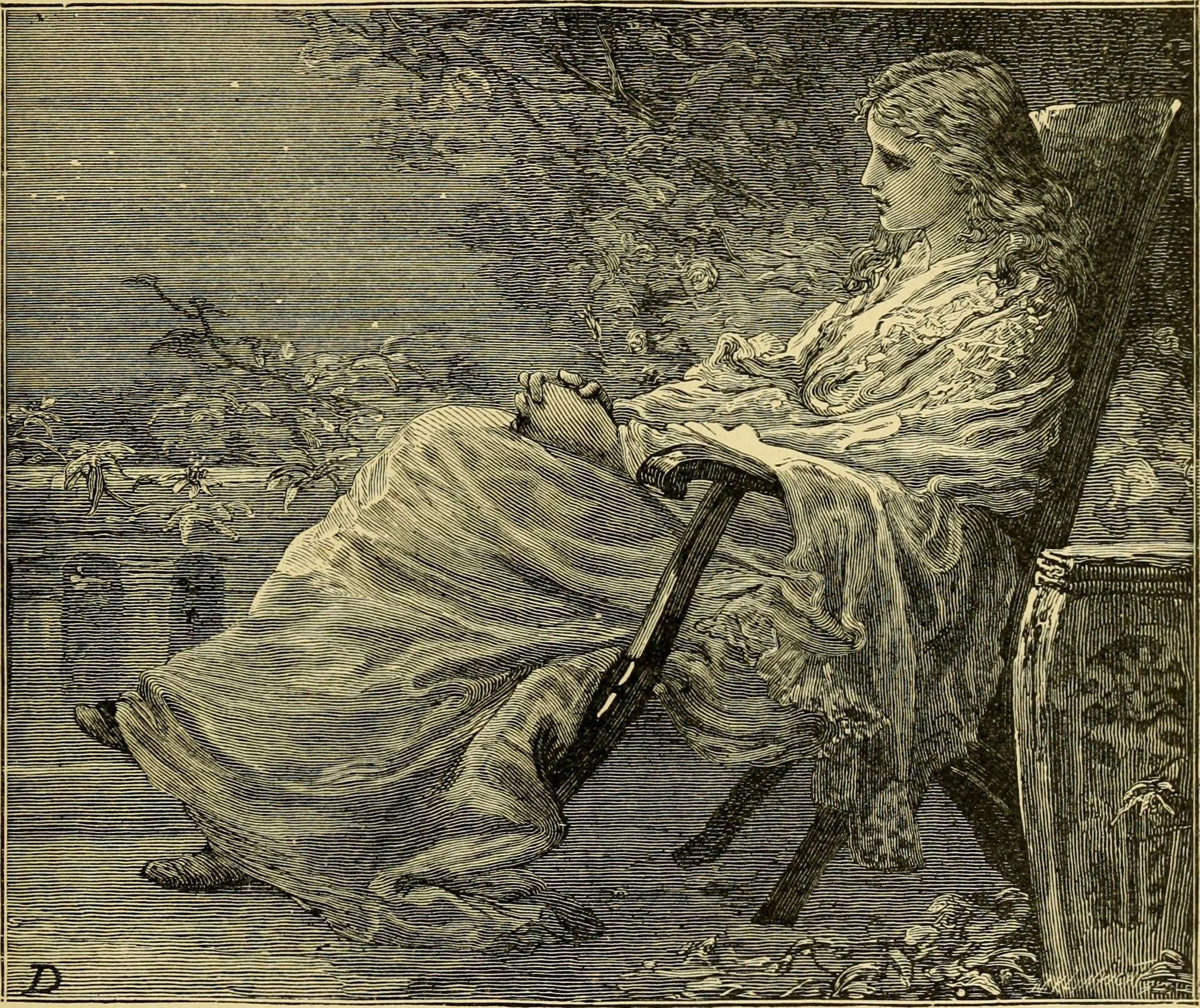

The connection between cosmetics and witchcraft

As for the people who make cosmetics, there are apothecaries, but there are also women within communities who tend to be experts in creating lotions and waters to beautify the face. It is these same women who are also making potions for things like love magic. These are dotted around different sources that suggest that these women who are talented at making things are also the type of women who are being accused of witchcraft.

© Gumberg Library via Wikimedia

© Gumberg Library via Wikimedia

In Italy, the witchcraft craze happens earlier than in the rest of Europe. There are certainly indications that women, these older women, women who are healers, are the ones who are being accused of witchcraft, often after they have given out healing potions or cosmetics to people in their community. There is this definite thread that links these people, who are experts in making things, experts in making cosmetics, to practices of magic — particularly in Italy, because love magic is so important. The idea that you can make a man love you through kissing him with particular ointment on your lips, for example, has clear relationships to the use of cosmetics, this idea of enchanting people through beauty. You get several instances of that in the archives, where women are accused of witchcraft because of beauty, or women supplying beauty products are also accused of witchcraft.

Reconstructing Renaissance recipes

Reconstruction used to be something that historians did not use at all, because they are rightly suspicious of it. When you reconstruct anything from a recipe in the past, you have to understand that much has changed, so the ingredients that we use, our bodies, our understanding of our relationship with the world is completely different to that of a person in the 16th century. We have to be careful about what we think we are doing with reconstruction. However, if you are studying recipes, and recipes are your main source of understanding of an entire culture — which they are with cosmetics — particularly with the cosmetics that poorer women were using, then reconstruction can give you a real insight into what people were expecting or hoping for from these recipes.

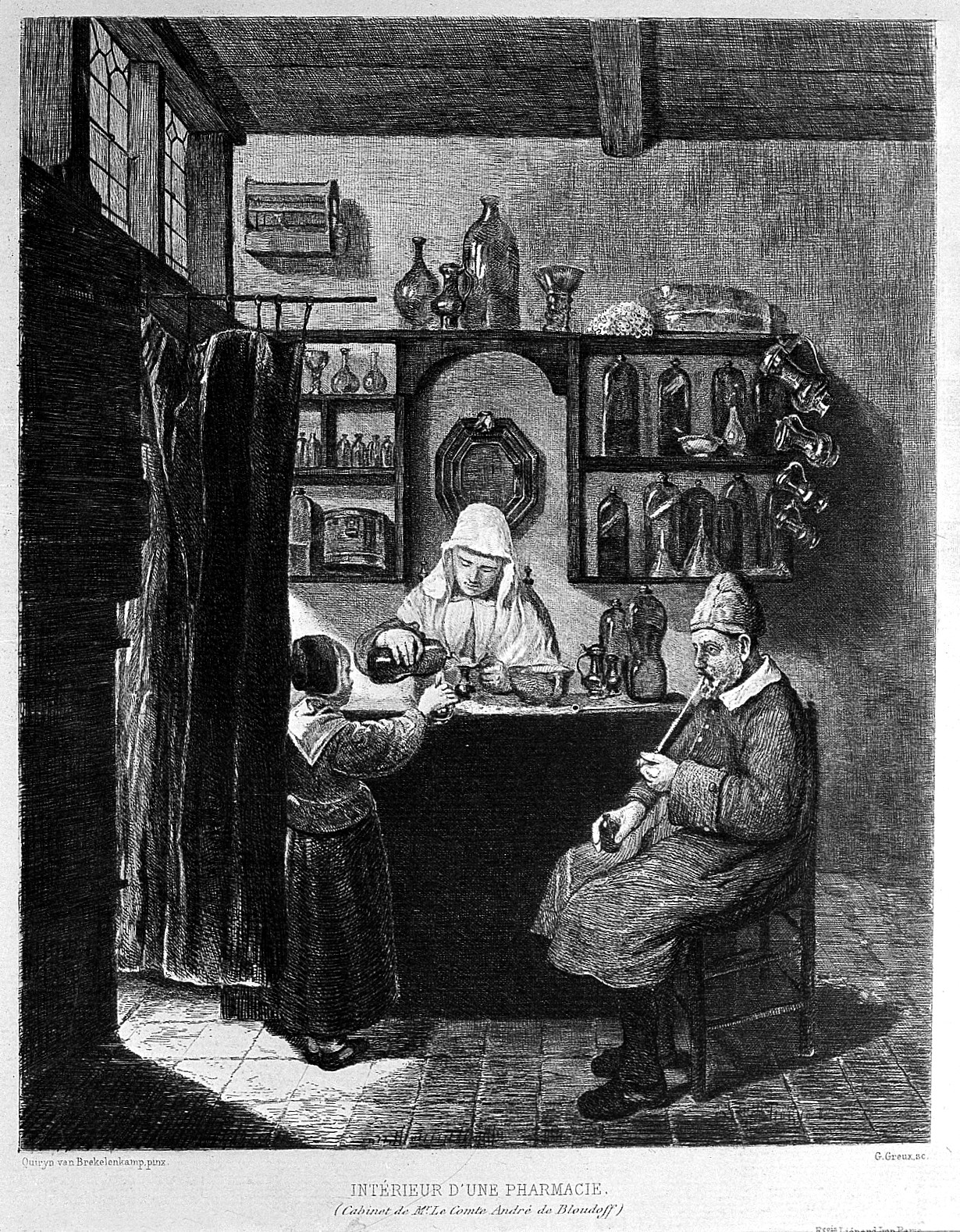

© Wellcome Collection

© Wellcome Collection

For example, reconstructing perfume gives an insight into the kinds of smells that people understood as normal, maybe that hid underlying smells at this time. I find that without reconstruction, it is really hard to look at recipes closely enough to understand very much about them. The material properties of the ingredients, too, were completely surprising to me. They used tree gums a lot in this period. Things like frankincense, mastic and benzoin are common ingredients, and these are things that I really was not familiar with at all. It gives you a different kind of insight into this whole massive non-verbal approach, a material, a bodily interaction with the world that I am finding really useful.

Making Renaissance cream

I can give you an example of a recipe that was surprising when we actually reconstructed it. There are several recipes in both handwritten and printed 16th century books that call for women to wash fat and then add it to various other ingredients to make a cream. I had no idea what washing the fat meant or why we should do this. It just seemed a strange, ritualistic thing, but I tried it anyway. I went through and got some sheep's fat as the recipe told me to, and I washed it. Then I mixed it up with egg whites and some tree gums, mastic and frankincense. This was a recipe for an anti-wrinkle cream. When we actually made the cream, it was astonishing because what it made was this fluffy cream that felt very much like a moisturizing cream you might get at the supermarket today. Washing the fat incorporated some water, and, with the addition of the egg, that allowed it to emulsify.

© EXPeditions

© EXPeditions

Instead of getting a fatty, greasy sensation on your skin, you got this kind of full cream that sank into the skin. The tree gums made it smell pleasant as well as adding antibacterial properties. What we found out by reconstructing that, for example, was that it was probably commonplace for women in a domestic kitchen to be able to make moisturizer in the 16th century. If we had not made that recipe, and we had not studied these, we would not have known about this quite impressive knowledge that women had in the past that now, since industrialization in a lot of Western countries, has been all but lost.

Body hair removal practices

It was very common for women to remove body hair in southern Europe in the 16th century. The sources are very difficult to interpret sometimes, but there are many, many recipes for body hair removal, which suggests that it was a common practice. Starting probably from the later Middle Ages right through the early modern period, these recipes appear in Italian books and French books — but not when the books are translated into English, interestingly. It also does not seem to be a practice in Germany. So, it is culturally specific.

Body hair was removed in baths. It was removed generally using a cream that was a combination of arsenic and quicklime. It is highly alkaline, and it melted the hair off the body. You would put it on, and in Caterina Sforza's recipe book, she says you should leave it on for as long as it takes to say an Our Father or a Hail Mary. You pray, leave it on; it melts the hair off, and then you quickly wash it off. Again, the fashion for it is related to two things. It is related to this influx of women from Spain who were exposed to Islamic bathing cultures, where hair removal was the norm. It is also related to a new fashion for classical statuary, where Venus, for example, is always shown completely hairless. There is this idea that women, real women, should not really have body hair or should have at most very, very sparse body hair. Women responded to this cultural change by increasingly removing their body hair.

Awareness of harmful ingredients

Renaissance women knowingly used makeup that could harm them and that was poisonous. They used it because the social stakes made it worthwhile. Skin whitening cream, for example — people knew that if you used mercury it was likely to stain your teeth black, and it was likely to have an impact on your health, but they used it because it was worthwhile for them. Their social impact was enough to make them take that risk. You see this, for example, in the Duchess Isabella of Aragon, who moved from Naples to Milan in the late 15th century and was derided for being dark skinned.

© Portrait of Isabella of Aragon, Fondazione Federico Zeri via Wikimedia

© Portrait of Isabella of Aragon, Fondazione Federico Zeri via Wikimedia

She became famous for creating a cosmetic recipe for skin whitening cream that included mercury, and we can see from her remains that have been analyzed by archaeologists that, indeed, her teeth were black, and she had tried to scrape off the top layer of enamel because they had blackened due to the mercury. It was worth it, presumably, for her as a young woman to try and attain this pale ideal that was so popular in Milan in the late 15th century. We also know that women knew very well that this makeup was poisonous, because sometimes they used it to poison people. There is a group of women who were condemned for murder in the 17th century in Rome because they created a water that they called "Aqua Tofana" that was made from arsenic, amongst other things, and they said they needed the arsenic to create makeup. In fact, they were using it to poison their husbands.

Feminist interpretations of Renaissance beauty culture

The work of feminists, from the 1970s, particularly through the 80s and 90s onwards, about beauty cultures and its effect on women's understanding of themselves and their own bodies has been obviously massively important to my work. I think it is absolutely true that people try and sell products by showing people that they have a lack, that their bodies are never good enough, that women's bodies are constantly works in progress. This is certainly the case in the Renaissance, in my period, too — people are trying to sell books and recipes by showing women that their bodies are not meeting an ideal.

© Pexels

© Pexels

There is a flip side to that as well. The flip side is the fact that there is creativity, knowledge and companionship in beauty culture, as well as this oppressive side. For many women, it can be fun; it can be funny; it can be humorous, and women can be aware both of being exploited but also of finding great pleasure in beautification.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

Cosmetics in the Renaissance

Burke, J. (2024). How to be a Renaissance woman: The untold history of beauty & female creativity. Wellcome Collection.

Burke, J. (2018). The Italian Renaissance nude Yale University Press.

Burke, J. (2004) Changing patrons: Social identity and the visual arts in Renaissance Florence Penn State University Press

Burke, J., & Poon, W. (2024) Embodied experiences of making in early modern Europe: Bodies, gender, and material culture. In S. Bendall & S. Dyer (Eds.) (pp. 95–112). Amsterdam University Press.

Burke, J., & Poon, W. (2024) Renaissance Goo: Senses and Materials in Early Modern Apothecary Taxonomies and Soft Matter Science. In Ambix (pp. 367-392), Volume 71, Issue 4.