Histories of the Renaissance tend to be pretty self-congratulatory, even now, and we tend to forget the women who were scrubbing the floors and washing the linen of these great humanists. Most of those humanists had domestic slaves in their households, and that is a side of the Renaissance that we really need to uncover and think carefully about. There is also a sense in which longer histories of slavery often skip over the later Middle Ages. I think we are all profoundly aware of slavery in the ancient world, and we are all profoundly aware of plantation slavery in a later period, as we should be; however, we often tend to miss this period in the 14th and 15th centuries, when huge numbers of people were being trafficked around the Mediterranean, living stories of extraordinary suffering and often extraordinary resilience.

Slavery in the Renaissance

Associate Professor of Medieval History

- Late medieval Mediterranean slavery was mainly domestic and female, with women trafficked across the region.

- Enslaved people used contradictions in Roman, canon and local laws to sue for freedom or better treatment.

- Once driven by religion and geopolitics, slavery grew explicitly racial after Black Sea routes closed and Portuguese Atlantic slaving rose.

- Notarial and court records capture enslaved voices, showing resilience that contradicts the image of passive victims.

Studying medieval slavery

There are many reasons why studying the history of slavery in the later medieval Mediterranean is a really compelling subject. There is a sense in which these people have been written out of a number of well-known histories, which is deeply problematic, partly for reasons of truth-telling and partly for ethical reasons; these are individuals whose stories deserve to be heard.

The Chafariz d'El-Rey (King's Fountain) © Berardo Collection Museum

The Chafariz d'El-Rey (King's Fountain) © Berardo Collection Museum

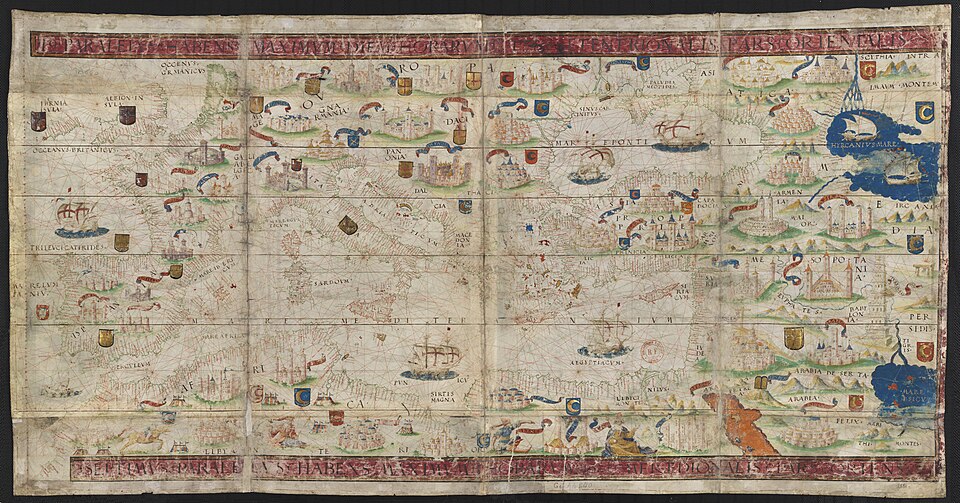

Geography of Mediterranean slavery

Slavery in the later medieval Mediterranean involves the entire Mediterranean coast – all the way around the Mediterranean. This includes southern Christian Europe, but it equally includes the north coast of Africa. Many of the slaves were being traded from much further east via the Black Sea port of Kaffa, which was a huge trading hub now located in Crimea.

1519 Portolan chart of the Mediterranean Sea by Lopo Homem from Atlas Miller © Gallica Digital Library

1519 Portolan chart of the Mediterranean Sea by Lopo Homem from Atlas Miller © Gallica Digital Library

I have been looking mostly at slavery in late medieval Christian Europe, including Dubrovnik in Croatia, which was then known as Ragusa. One can find slaves in areas around the coast of Italy, such as in Sicily and Sardinia, and also Crete. You can then trace around across the ports of southern France and right around the Iberian Peninsula as well. It is largely a coastal phenomenon, but then it moves into the lands of what we now know as Italy and Iberia. Things get really interesting once you move a little bit further north, in fact. It is very much a slaving zone focused on Mediterranean society. As you move further north, you do not find enslaved people in the later Middle Ages.

Who were the enslaved?

Most of the enslaved people in this period were women, and the kind of slavery we are finding in this period is overwhelmingly domestic.

"Eve spinning", folio 8r, detail from the Hunterian Psalter © Glasgow University Library

Most of them were trafficked women working in domestic roles in households across the Mediterranean. That is not to say that no men were enslaved in this period. Men certainly were, too. It is not to say that there were not people being used in agricultural work; that was also happening. However, the particular demographic and socioeconomic patterns we are seeing at this point mean that the most lucrative thing for owners and traffickers to do was to place women in domestic slavery.

It may be obvious that much of the domestic slavery must have involved sex work as well. A lot of that seems to have been sex trafficking, though theoretically that was forbidden. However, that was quite clearly what was going on in many of these cases. People could be enslaved for a number of reasons; they could be enslaved through capture in war, according to the laws of war in various cultures across the Mediterranean.

They were not supposed to be enslaved if they were Christian. Canon law said that Christians should not enslave other Christians, but that left several loopholes and questions about different sects and movements, which certainly were Christian, but which some Catholics were able to claim did not count.

Sources for enslaved voices

I am particularly interested in the slaves themselves: in these enslaved people and the way they dealt with the circumstances in which they found themselves, how they expressed themselves, how they tried to slightly better their conditions. Amazingly, we have the source material that enables us to do this. The 14th century sees a huge expansion of notarial culture in southern Europe in particular. Notaries are busy recording contracts, recording sales of all these different transactions which are taking place, and we have those registers which enable us to trace the movement of people and sometimes to get a bit more information about them.

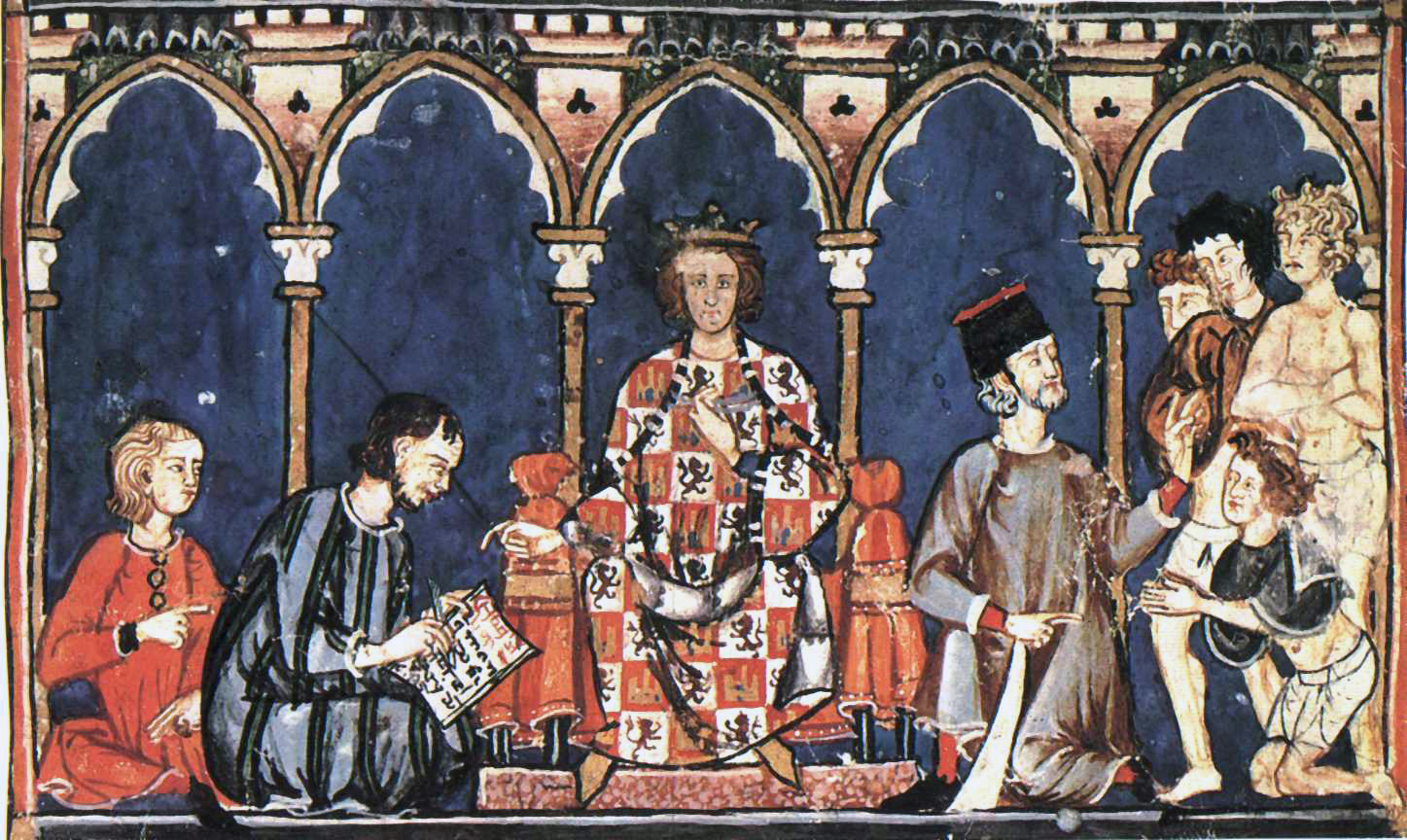

Alfonso X el Sabio © Four Gothic Kings, Elizabeth Hallam via Wikimedia

Alfonso X el Sabio © Four Gothic Kings, Elizabeth Hallam via Wikimedia

We also, extraordinarily, have records of litigation sometimes initiated by the enslaved people themselves. Part of the reason for that is that most of southern Europe came under Roman law, but there were also a range of other kinds of laws in operation. There was canon law, which is the law of the church. There were customary laws which were different in different localities. There were statute laws of particular cities. All these laws layered onto one another, but not precisely, so there were little gaps, little interstices, between the different forms of law. I have been particularly interested in the ways in which slaves themselves were able to exploit these gaps between different kinds of law, push them apart and take cases to court, where they could seek slight betterments in their conditions by working with different kinds of laws that were in operation in that period.

Challenging enslavement in court

There is a fascinating case of a woman in the records known as Maria the Hungarian. This is from 1479, and she brought a case to court in Genoa, Italy, to where she has been trafficked. She said in this case, which she had initiated, that she had been wrongly enslaved. Apparently she was captured by Ottoman Turks, then sold to two men and trafficked to Genoa. She said she should never have been sold to these men nor trafficked as a slave because she was a Christian.

A view of Genoa and its fleet © Christoforo de Grassi, Galata Museo del Mare, Genoa

A view of Genoa and its fleet © Christoforo de Grassi, Galata Museo del Mare, Genoa

She took the case to court and argued her case, which is just extraordinary. We do not know precisely the mechanisms by which someone in such an utterly disempowered position was able to do this, but she brought her case, and the court decided in her favor. The commune of Genoa, represented by a set of judges, decided that Maria was a Christian and, therefore, should not have been enslaved. The people who bought her claimed that they rightfully bought her, because she had been enslaved by the laws of war. Maria put canon law, which said Christians could not be enslaved, against the laws of war, which said people could be enslaved through war – and she won her case.

There was a sting in the tail, very sadly, because the men who trafficked her then said, well, if we did not buy her as a slave because she was a Christian, then we ransomed her from the Ottoman Turks. If we ransomed her, we paid that ransom and, therefore, she owes us the money for that. Of course, Maria had no money with which to pay them, so she then found herself in debt bondage to them for an indefinite amount of time until she could pay the money back. Ultimately, this is a very sad story, but it shows us an enslaved person able to push apart these gaps between different kinds of law.

Stories of freedom

Enslaved people could theoretically save up a sum of money in order to purchase their manumission or freedom. That was one way in which one could gain freedom. By Roman law, enslaved people were able to save up a pot of money known as a peculium, which meant that, for various extra tasks they might be doing, they might be minimally paid by their owners or by others, and they could save this up in order to eventually buy their freedom. It was very unusual for people to be able to save up enough to buy the full nominal value of themselves, so they were heavily reliant on the goodwill of their owners. Very often their owners would use this as an example of what great Christians they were that they agreed to one of these transactions.

Dubrovnik © Maritime Museum in Dubrovnik

There is a particularly moving case in Dubrovnik from the early 14th century of a woman named Dabracha, who saved up her peculium to buy her freedom, but there was no way she could save up enough. Rather wonderfully, her sister, a woman named Zueta, helped her by providing half of the sum of money that Dabracha needed in order to purchase her freedom. Even this was not enough. The only way Dabracha could actually raise enough money to purchase her manumission, or her freedom, was by selling her labor to another man. She sold her labor for a set number of years, so she effectively exchanged a slavery contract, which is described in the sources as usque ad mortem – right up to death – for a contract of indentured labor, which says usque ad quattuor annos – up to four years. She sold the labor to work for someone else for four years, plus the money from her sister, plus her own savings. It is a rather extraordinary story of family solidarity.

Slaves resisting legally

There is another extraordinary story of three girls, also from Dubrovnik, named Galatea, Stoyana and Tadislava. I describe them as girls because they were still teenagers; they were really very young. I think they must have found some solidarity with one another, because the three of them went to court together to say they had been wrongly enslaved, because they were Christians. This should not have happened. They had been captured in the hills around Dubrovnik and trafficked into the city wrongly. They very interestingly understood the niceties of canon law on this question. They also understood that Dubrovnik, as a city, was quite keen to set itself apart, and they referred to the specific statutes of Dubrovnik. Again, extraordinarily, they won their case.

Rector's palace, Dubrovnik © JoJan via Wikimedia

The councilors and judges of Dubrovnik set them free. We know about this partly because there was then a long battle from the man who bought them with the people that he had apparently commissioned to go off and find him some slaves in the countryside so that he could get compensation. That whole process of seeking compensation also tells us about the extraordinary courage of these girls.

Mothers fighting for their children

By Roman law, which was the official legal framework in many of these areas, children of enslaved women inherited the slave status of their mothers. In many of these cases, the fathers were the owners. Sometimes we know that; sometimes we can just guess. Even in such cases, the children inherited the status of their mothers, so this was emphatically matrilineal. Nevertheless, there are many cases in which we find enslaved mothers fighting for the rights of their children and refusing straightforwardly to accept that this was how things were.

"Tacuinum Sanitatis" via Wikimedia

"Tacuinum Sanitatis" via Wikimedia

I came across a very interesting case of a woman in Perpignan – now in southern France, then part of the Kingdom of Aragon – and this woman was pregnant. Before she had the baby, she went to court to claim that the father of this child was not her owner but a local miller from a nearby village called Elne. By Roman law, that should not have made any difference, because the child would inherit the mother's status, but in this case this woman knew that there were question marks over how that status would in fact be inherited and that local customary law was so emphatically patrilineal that the child could possibly inherit the status of the father. It really mattered to her to go to court to claim that the father was this miller rather than her owner. We do have a situation in which children are supposed to inherit the status of their mothers, yet we find a number of cases where that is not what happens because of a clash of different legal norms. We also find a number of cases of these extraordinarily courageous mothers who somehow get themselves to court to argue the case for their children.

Race and late medieval slavery

Slavery in this period was emphatically defined through law. A slave was made a slave through law, which makes it all the more extraordinary that enslaved people themselves were willing and able to challenge the slave-making possibilities of law. Given that law was there emphatically to take away all their rights, it is extraordinary that they used law in order to claw back some of those rights.

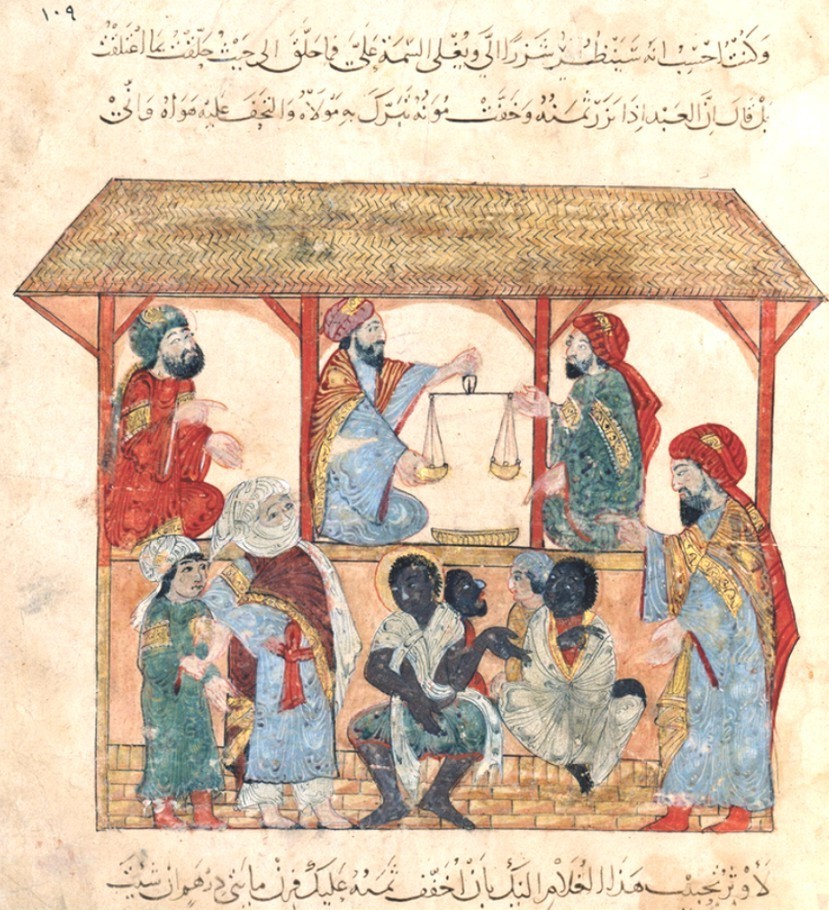

What is also very striking is that in this period race did not seem to play a huge role in the ways in which people were thinking about slavery. Religion did, and geographical provenance did, in the sense that this had everything to do with geopolitical shifts. In some ways, of course, we might want to think about religion, ethnicity and geopolitics as related to concepts of race, but it was certainly not racialized in the way that slavery was in a later period. What is very striking is that over the course of the 15th century, slavery does become increasingly racialized. Part of that was due to lack of access to Black Sea ports, particularly after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, and it was also due to Portuguese slaving expeditions and expansion down the west coast of Africa.

Marché aux esclaves à Zabid au Yémen © Bibliothèque nationale de France via Wikimedia

Marché aux esclaves à Zabid au Yémen © Bibliothèque nationale de France via Wikimedia

There were geopolitical shifts and shifts in who is being enslaved, and there were discourses that accompanied that which justified slavery increasingly in explicitly racialized terms. However, that was really toward the end of the period I am looking at, and it is very striking that most of the time this phenomenon was not conceived of in such terms. There was a very strong sense that to be enslaved was bad luck, that it was to do with a set of contingent circumstances that placed an individual in a horrible situation.

Justice and resilience under oppression

I do not want to romanticize the story of enslavement in this period. Fundamentally, this is a story of extreme suffering, oppression, persecution and exploitation. Alongside that, though, there are a number of really inspiring stories of courageous individuals willing to support enslaved people. The story of Antoine Simon, the enslaved man who escaped to Barcelona, shows this: he was supported by a man named Pierre Tocque, who was willing to go all out to help him. The real hero of that story was Antoine Simon himself, the enslaved man who risked everything to escape across the mountains.

Medieval representation of a sheep pen in the Luttrell Psalter © Linda Kalof via Wikimedia

Medieval representation of a sheep pen in the Luttrell Psalter © Linda Kalof via Wikimedia

To me, the other really interesting feature was the ways in which people in positions of extreme oppression were able to use law. Their understanding of legal mechanisms, their understanding of what law could offer them and the possibility of using the courts to improve their circumstances is really extremely interesting. I think that legal consciousness is a feature of the Middle Ages that deserves to be taken very seriously.

Slavery and Renaissance liberty

A recent book by Hannah Barker has argued very compellingly that when we talk about Mediterranean slavery, we are talking about a common slaving culture; Christian communities and Muslim communities were all involved in the same process, albeit with rather different legal systems doing this. Nevertheless, alongside this sense of an overall slaving culture, we can see very distinctive ways in which it operated in different areas, and it was that sense of distinctively local laws and customs which enslaved people were often able to use slightly to their advantage.

The other striking thing, of course, is that this was also a period when humanists and intellectuals were talking about liberty – concepts of liberty and freedom in an intellectual, political-theoretical sense – more than ever. Trying to address head-on the hypocrisies or dissonances between the prevalence of slavery in this period and this discourse of liberty is really important ethically.

Challenging slavery myths

I would like to primarily address three misconceptions. The first is that there is very little slavery in this period, so that in longer histories of slavery this is not a period which deserves attention. In fact, the later Middle Ages are an absolutely crucial moment, not just in the sense of transition from one form of slavery to another; this is a distinctive period which operates in distinctive ways.

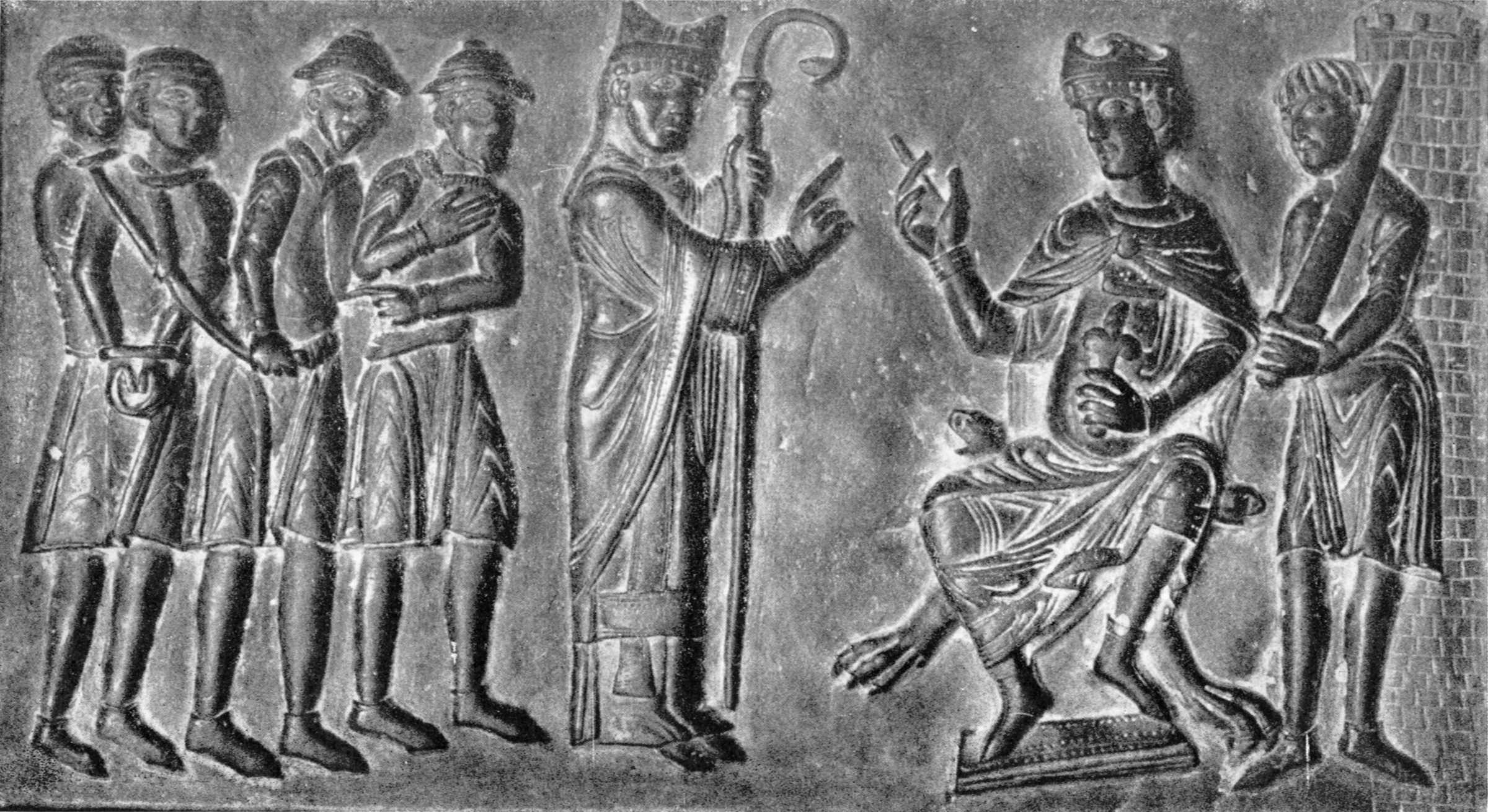

Saint Adalbert of Prague pleads with Boleslaus II, Duke of Bohemia, for the release of Christians slaves by their masters © Gniezno Cathedral Door via Wikimedia

Saint Adalbert of Prague pleads with Boleslaus II, Duke of Bohemia, for the release of Christians slaves by their masters © Gniezno Cathedral Door via Wikimedia

The second misconception I would like to address is the self-congratulatory narrative of the Renaissance to which we are so often drawn. The sense that these intellectual shifts and paradigm-shifting ways of thinking about political theory, life and art are underpinned by stories of exploitation and oppression is extremely pressing.

The third misconception is that people in these situations are just victims. Many of these people were victim-survivors. Their stories of resilience, legal know-how and courage are really extraordinary, and their humanity deserves our attention.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

late medieval slavery and legal culture

Skoda, H. (2023). Slave voices and experiences in the later medieval Europe. History Compass, 21(10).

Skoda, H. (2018). People as property in medieval Dubrovnik. In G. Kantor, T. Lambert, & H. Skoda (Eds.), Legalism: Property and Ownership (pp. 235–260). Oxford University Press.

Skoda, H. (Ed.). (2023). A Companion to Crime and Deviance in the Middle Ages. . Amsterdam University Press.

Kantor, G., Lambert, T., & Skoda, H. (Eds.). (2018). Legalism: Property and Ownership. Oxford University Press.

Barker, H. (2022). That Most Precious Merchandise The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 1260-1500. University of Pennsylvania Press.