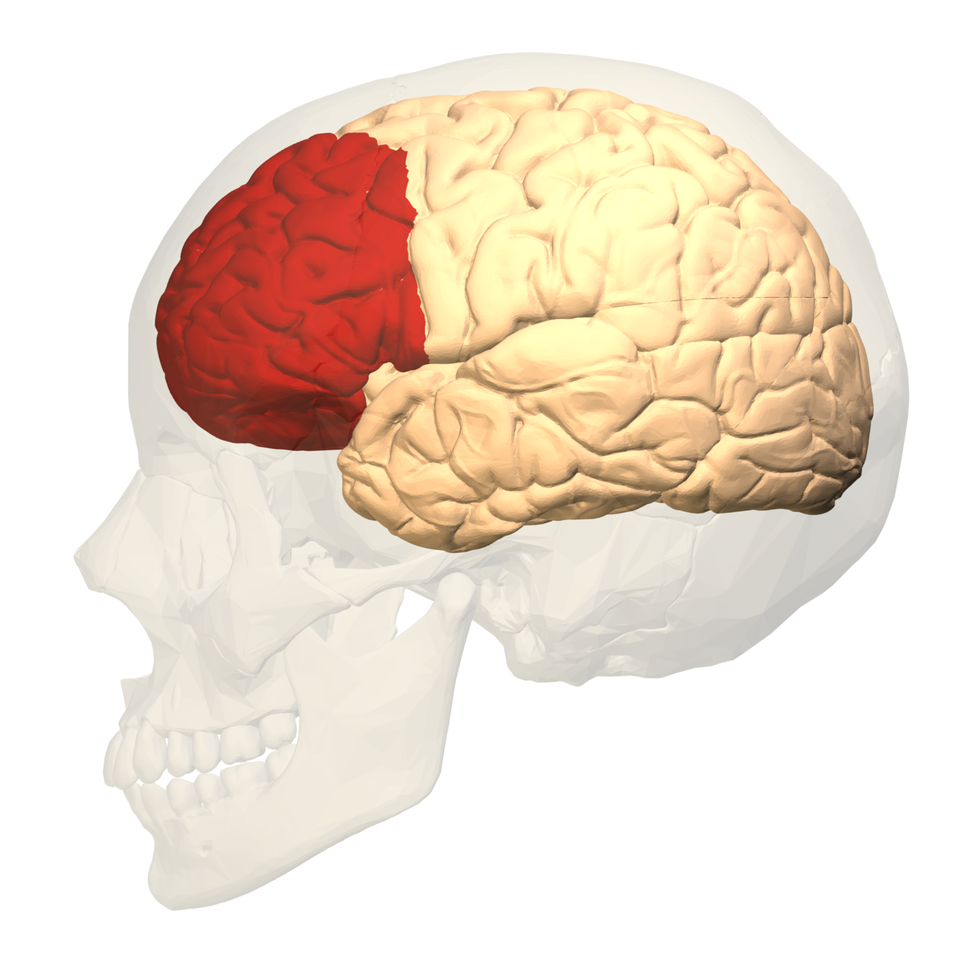

It is this region that, when it is damaged, can often lead to problems with self-awareness and with insight into changes in cognition or memory. We have been exploring, using brain-imaging techniques such as functional MRI, what contribution the different subregions of the prefrontal cortex make to this capacity to judge ourselves.

Exploring metacognition

Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience

- Metacognition is the mind’s ability to monitor and evaluate its own perceptions, memories and decisions, forming the basis of self-awareness.

- Circuits in the prefrontal cortex generate confidence signals; damage or dysfunction in these networks erodes insight into one’s performance.

- Precise self-assessment steers high-stakes behavior, from freediving limits to Stanislav Petrov’s pause that averted nuclear war, by preventing reckless or overly cautious choices.

- Distorted self-evaluation fuels anxiety, depression and rigid beliefs, yet targeted training and practices like meditation can restore more accurate metacognitive judgment.

Defining metacognition

Metacognition literally means cognition about cognition or thinking about our own thinking. In our research, it is a broader topic than that. It refers to reflection on our own mental states, our own perceptions, our memories and our decisions. For instance, we can introspect about whether a memory of last year's birthday party is actually real, or perhaps we have just imagined it. We can reflect on whether we have made a good or bad decision, and these are all aspects of metacognition enabling us to self-assess our own mental processes.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

When we self-reflect

One question we have is what is happening in the brain when we self-reflect. For a long time, we have been interested in the role of the prefrontal cortex in the human brain, the area of the brain right toward the front of the head.

© Database Center for Life Science

© Database Center for Life Science

Confidence in performance

The task that we have developed to study metacognition using brain imaging involves people making simple judgments about what they see on a computer screen and then evaluating how confident they feel in making those judgments. We can quantify how good your metacognition is by the extent to which your confidence is tracking your underlying performance. What we find is that people who have better metacognition have subtle differences in the function and the structure of particular circuits in the prefrontal cortex. Brain activity in these networks is linked to the formation of this metacognitive judgment; it predicts how confident you will feel in individual decisions or actions that you make. We think that this research can start explaining why, if you have damage to these networks, you might have problems with self-awareness, because you are damaging the brain circuits that are creating this model of how you are performing in a particular task.

Brain damage

Brain damage or dysfunction to these regions can occur for a variety of reasons. These include stroke and the consequences of having brain surgery to remove tumors, but it can also occur for more subtle reasons. For instance, dementia or certain psychiatric conditions might lead to subtle changes in how the circuits within the prefrontal cortex and other areas of the brain are working, and we think that is one reason why, in a number of different psychiatric and neurological conditions, you might see these changes in metacognition.

Decisions and performance

Metacognition, we think, plays an outsized role in how we make decisions and how we navigate our daily life, because it allows us to form estimates of how much capacity we have, how much skill we have in particular areas of endeavor. One nice example comes from the world of sports, extreme sports in particular. In freediving, people have to estimate very precisely what they will be capable of.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

Freedivers need to dive without any oxygen to as deep as they can go and then return to the surface. It is a balance between being able to push the limits of what you are capable of and not overstepping them, because that can lead to injury or even death. In cases like this, you need to have a really precise estimate of your own capacity, and no one tells you that from the outside. This is something you need to find out and explore yourself. Areas of sport and elite performance are nice cases in which this metacognitive aspect of performance becomes exposed.

Modeling people’s behavior

The types of computational model we build in our lab are algorithmic models that are trying to explain aspects of people's behavior. We can build models that characterize people's metacognitive judgments. These are models that simulate probabilities of success on various tasks, and we try to derive equations that predict how people will rate their own confidence in those same tasks. We think there is a deep connection between representing a probability of success and how you evaluate your confidence; the fluctuations in your performance inform the model you have of yourself.

© UCL

This approach is part of a broader class of models known as predictive processing accounts. The predictive processing framework suggests that what the brain is trying to do is build a model of the outside world, actually in a similar way to which we as scientists are trying to build a model of how the brain itself is working. In the case of humans, one aspect of that model of the outside world includes ourselves; it includes our own decisions and our own actions. We think one powerful approach for modeling metacognition is to develop a predictive processing account that includes ourselves, our actions and our decisions in that model, and that can provide a really powerful and flexible account of how people form confidence in their perceptions, in their memories, in their decisions, really in anything that the brain is set up to do. We can also take this up to a metacognitive level and study how people can self-assess those brain processes.

Sitting with uncertainty

Stanislav Petrov is a fascinating character. He was a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet military in the 1980s, and he was on duty one morning in September 1983 when he was monitoring these early-warning satellites that told him there was an incoming missile attack. The doctrine at the time required him to pass this information up the chain to allow for an immediate response. Rather than doing this, he paused and reflected on what he was seeing — these alarms going off — and thought to himself, this is more likely to be a false alarm than a real attack. He was proved right, and he arguably did more than anyone else in human history to avert a worldwide nuclear disaster.

Stanislas Petrov; Wikimedia

Stanislas Petrov; Wikimedia

What Petrov's story tells us is something about the value of seeing the world not in black and white but in shades of grey — the value of sitting with uncertainty about what our senses are telling us, whether the information we are being given is true or false, whether the picture we have of the world is a reality or perhaps an illusion. This aspect of second-guessing ourselves is core to having good metacognition, to having good self-awareness, and the story of Petrov shows us that that can have an outsized impact on the types of decision we go on to make, even in very high-stakes scenarios.

Underconfidence and mental health

Our lab and other labs around the world have found links between mental health symptoms such as anxiety, depression, compulsivity and changes in how we see ourselves — changes in these metacognitive processes.

© Pexels

© Pexels

For instance, people who have more anxiety and depression symptoms will tend to be under-confident about their own skills and abilities. This can be pernicious, because it can then lead you to not pursue new opportunities, even if you are perfectly well qualified to take on a new role at work or to join a new sports team. You might not feel as though you have the skill or the ability to pursue those avenues. These distortions in how we evaluate our own skills and abilities can then lead to consequences in the actions and decisions we take.

Improving metacognition

One area we are very interested in is the promise of developing new treatments and new interventions to improve or reshape metacognition in beneficial ways. There is a growing line of research looking at the benefits of meditation for self-evaluation.

© Pexels

© Pexels

Work done in my lab has also shown promise for training — coaching people to realize when their self-assessments are distorted or not in line with the reality of their performance. Very recently, together with a postdoc in my group, Sucharit Katyal, we developed computational models to show that, in cases of anxiety and depression, the reason people might hold these distorted views of themselves, in terms of having systematic underconfidence in their skills and abilities, could be due to a failure in how they learn about their own performance. It is not that we are getting told how well we are doing in various aspects of our lives; we have to infer that from various cues. We found in studies we conducted recently that those distorted self-assessments might have their root in distortions in learning how metacognition updates over time.

Metacognition and free will

There are two ways of approaching the debate over free will. One is through the lens of physics and fundamental properties of the universe — the debate about whether there is really any randomness in the universe or whether everything is predetermined. That is not a useful perspective on whether humans have a psychological sense of free will. Regardless of how the universe is structured and how determinate it really is, that does not have much bearing on whether we as humans feel like certain choices we make are free in the sense of acting for our own reasons, or somehow under duress, or an action that we took without thinking, or for reasons other than those we wanted in the first place. That notion of free will is very tractable psychologically because we can start understanding why someone might make a certain choice in a certain situation. I think metacognition has a role to play in that explanation, because often the choices that we think of as being most free and in line with our own wishes and desires are those which we reflectively endorse. If I make a decision about where to go on holiday, and then after making that decision think to myself, that was a good decision — that is exactly how I would want my holiday to unfold, then that can be considered a decision that was entirely in line with my own wishes and desires. That is separate; it is unrelated to whether those wishes and desires were in some sense caused by previous events. The freedom has its locus within me as an agent rather than being a fundamental property of any physical system.

Metacognition against misinformation

Like many psychologists, I am worried about the consequences of misinformation for how people form beliefs about the world. Our research on metacognition suggests that an important component of how we form beliefs is the capacity to reflect on whether we have an accurate belief or not.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

If we realize that perhaps the way we are seeing a problem or an issue is distorted or misinformed, then that is a prompt — an internal signal that we can use to seek out corrective information, to ask others for their opinion and so on. We think that that metacognitive aspect is important for people resisting polarization and misinformation. One reason why we think there is a linkage is that, in our work in the lab, we have shown that the extent to which people hold rigid and dogmatic beliefs about real-world issues such as politics can be predicted by the profile of their metacognitive judgments on simple laboratory tasks. People who are more willing to admit mistakes or errors in laboratory tasks are also those who tend to have less rigid or dogmatic views about political issues. We think there is some general component of metacognition that contributes to enabling people to hold more moderate views about the world.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

metacognition

Fleming, S. M. (2021). Know thyself: The science of self-awareness. John Murray Press.

Fleming, S. M., & Daw, N. D. (2017). Self-evaluation of decision-making: A general Bayesian framework for metacognitive computation. Psychological Review, 124(1), 91–114.

Fleming, S. M., & Dolan, R. J. (2012). The neural basis of metacognitive ability. Psychological Review, 124(1), 91–114.

Fleming, S. M., & Lau, H. C. (2014). How to measure metacognition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 443.

Katyal, S., Huys, Q. J., Dolan, R. J., & Fleming, S. M. (2025). Distorted learning from local metacognition supports transdiagnostic underconfidence. Nature Communications 16(1), 1854.

Dennett, D. (1993). Consciousness Explained. Penguin.