The ancient Greek world stretches from Spain in the west to Cyprus in the east, and from the Crimea in the north to Cyrenaica in Libya in the south. It is truly a very expansive and geographically fragmented entity. When we look at this map, it is very clear that migration is a crucial part of what made the ancient Greek world. It must have been crucial in the way this world came together, but it also must have been crucial in keeping this world linked and connected. The ancient Greek world must, just from looking at its map, have been a place characterized by human migration, human mobility, throughout all of its history.

Migration in ancient Greece

Professor of Greek Archeology

- The ancient Greek world was vast and geographically fragmented, and migration was essential to its formation and cohesion.

- Mobility was continuous and often circular rather than a single outward diaspora, culminating in cultural convergence that created a shared Greekness.

- Greek communities were bound more by shared language, ritual and everyday practices than by common laws or institutions. What archaeology shows us is that culture comes first and identity follows after.

- Migration is not new; people have always moved around, and mobility is a fundamental part of the human condition.

The ancient Greek world

If you have a look at a map of the ancient Greek world, it is much bigger than the borders of the modern nation state of Greece.

Map of Greek (red labels) and Phoenician (yellow labels) colonies around 8th to 6th century BC © Gepgepgep via Wikimedia

Map of Greek (red labels) and Phoenician (yellow labels) colonies around 8th to 6th century BC © Gepgepgep via Wikimedia

Researching human mobilities

It is been a major focus of my research to try and understand the nature of these human mobilities, both the mobility that created the ancient Greek world in the first place, but also the kinds of mobilities that held it together over the course of its history.

Ancient Greek warship © Greens and Blues via Shutterstock

Ancient Greek warship © Greens and Blues via Shutterstock

Five years ago, I started a new research project. It is called Migration and the Making of the Ancient Greek World, or MIGMAG for short. My aim in this project was to investigate the kinds of mobilities that created the ancient Greek world, that gave it the initial shape that we see on the map today.

I wanted to understand how the Greek world became so geographically expansive, to understand how Greeks got to these various far flung locations and then what held them together afterwards.

Centers and peripheries

My research begins at about 1100 BCE, in the early Iron Age. At this point in the Mediterranean, this is an environment which is extremely decentralized. There are no large political states. There are no empires, so there is a lot of flexibility, a lot of fluidity, and there is a lot of people moving around.

The Sanctuary of Athena Pronaia (Delphi) © George E. Koronaios via Wikimedia

The Sanctuary of Athena Pronaia (Delphi) © George E. Koronaios via Wikimedia

In this period, there is no clear idea of a center or periphery. There is no clear idea of people necessarily moving out in a diasporic sense. It is much more chaotic. We are much more thinking about people moving around in a Brownian motion, almost without clear directionality. What is interesting is that over the course of two or three centuries, a directionality emerges, and we start to find emerging centers and emerging peripheries.

What I think is particularly interesting are the processes through which the centers emerge as centers, and the peripheries emerge as peripheries.

Expanding networks

We can start to see, for example, an increasing intensity of communications around the island of Cyprus in particular. In the early Iron Age, it becomes a hub for the export of metals, raw metals in particular, which is going to drive the full flowering of the Iron Age.

Bronze bowl with handles terminating in lotuses, Cypro-Geometric III, ca. 850–750 BC © The Cesnola Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bronze bowl with handles terminating in lotuses, Cypro-Geometric III, ca. 850–750 BC © The Cesnola Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cyprus, because of its natural resources, then becomes an important node for Mediterranean communications, and it is incredible to see how these networks expand and get more intricate over the course of time.

Cultural commonalities

The ancient Greek world at this time, in the classical period, is not a single political entity. It is not comprised of any contiguous territories. Instead, it is made up of hundreds — actually, more than a thousand — individual autonomous communities. Many of these are city states, famously known as the Greek polis, but some of these might be territorial states, too. What is unclear is what holds together all of these diverse groups. They are not held together by any common political institutions. They are not held together by any common laws.

Polyxena Sarcophagus © Çanakkale Archaeological Museum via Wikimedia

Polyxena Sarcophagus © Çanakkale Archaeological Museum via Wikimedia

Instead, what they seem to share are cultural commonalities, in terms of language, in terms of ritual, in terms of ways of life, ways of doing things, but also in terms of their idea of a shared history, the stories and the mythology that they shared, too. The ancient Greek world at this time is a world held together by shared culture rather than by any formal political structures.

A shared common Greekness

Traditionally, we as modern scholars have always assumed that this Greek world was created by a form of diasporic expansion, that the ancient Greeks start out in the Aegean, in the area which is now the modern nation state of Greece. We assumed they expanded from there and colonized all these various parts of the ancient Greek world.

Boats cup, detail of the interior showing a frieze of five boats in contest. Attic black-figured cup, ca. 520 BC. From Cerveteri © Museum of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Boats cup, detail of the interior showing a frieze of five boats in contest. Attic black-figured cup, ca. 520 BC. From Cerveteri © Museum of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

What we now know as a result of my research and the research of others is that it is more complicated than that. Actually, the movements are not diasporic in nature. They do not start in the Aegean and then go outwards. The movements tend to be much more circular around regional areas, and then they almost tend to be drawn inwards at a later date.

Culture first

We tend to think of migration as something that happens one-off or in discrete moments in time, such as the idea of a diasporic expansion of Greekness. We are actually dealing with a situation where migration is much more ongoing, much more cyclical, much more normal, much more everyday.

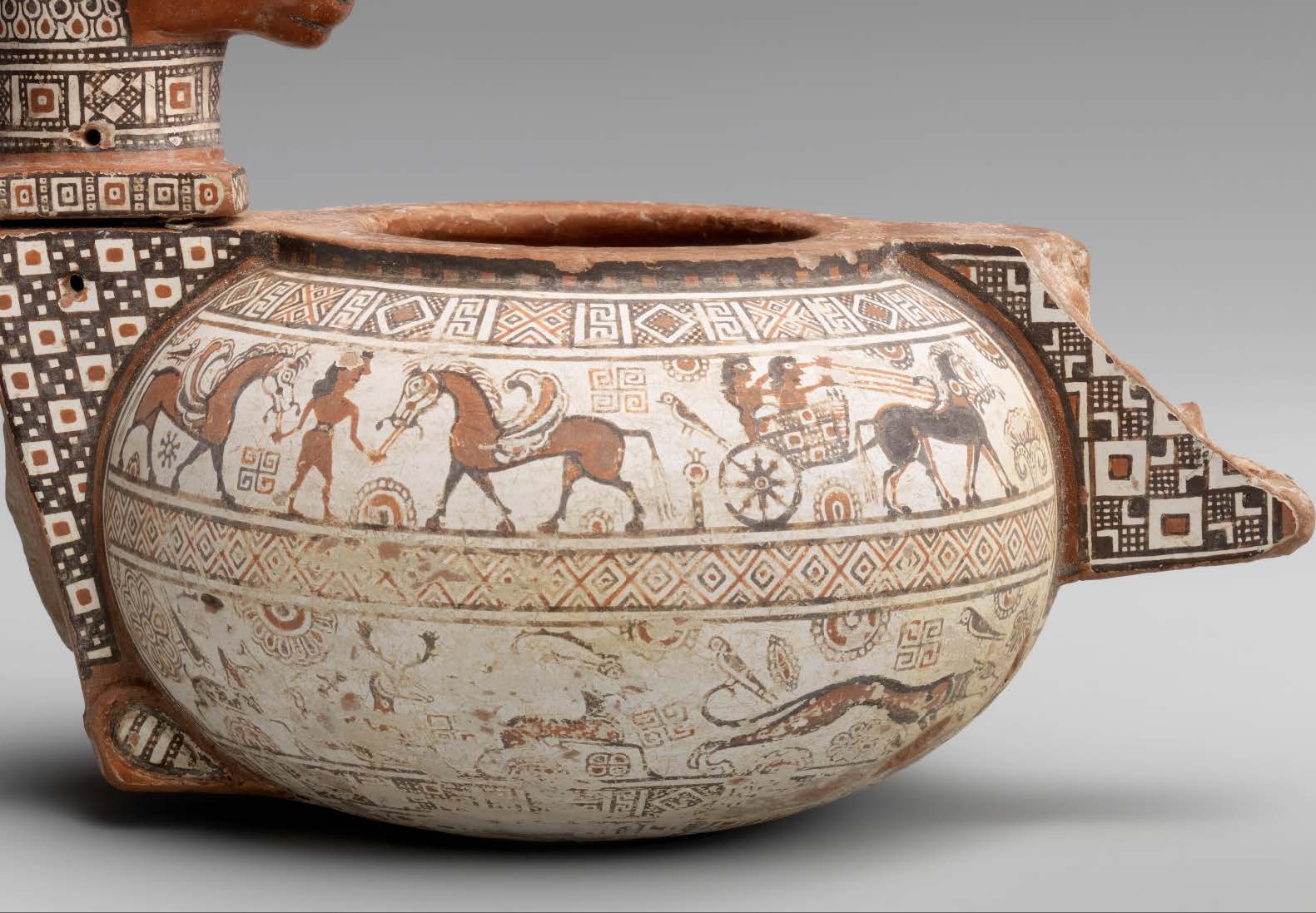

Terracotta cosmetic vase, 4th quarter of the 6th century BCE © The Bothmer Purchase Fund, 1977, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Terracotta cosmetic vase, 4th quarter of the 6th century BCE © The Bothmer Purchase Fund, 1977, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

What actually creates the ancient Greek world is not a diasporic expansion outwards but instead a cultural convergence, whereby interacting communities look inwards and then create this idea of a shared common Greekness.

What we see in the archaeological record are groups of people beginning to partake in and embrace Mediterranean style cultures and customs and ways of life. It is those ways of doing things, styles of eating, styles of drinking, ways of worshiping the gods, which are beginning to show cultural convergence first and then these more explicit statements of identity, origin and ethnicity; these are things which come later. What archaeology shows us is that culture comes first and identity follows after.

Migration is normal

I think if there is one thing we can take from this research, it is that migration is normal. It is a normal state of being for humans to move around at different scales, not necessarily long distance migration over huge distances, but a general ongoing sense of humans shifting places, humans being mobile.

Fresco from bronze age excavation at Akrotiri (Santorini) © National Archaeological Museum of Athens

Fresco from bronze age excavation at Akrotiri (Santorini) © National Archaeological Museum of Athens

I think what we can learn is that whether you call something migration is just a label. At the point at which it is unusual enough to be labeled as migration rather than as mobility, this is something which very much changes over time. What we might call a migration movement might have been something quite normal and everyday for someone in antiquity, and vice versa.

The first lesson is that human mobility has always happened. It is always ongoing. It never stops. It is a normal condition of humanity. The second lesson is that how we understand those mobilities is quite culturally specific. The same movement might be understood as an unusual form of migration in one period of time, but it might just be a normal part of everyday life in another historical period.

If there is one misconception I would like to correct, I would like people to be aware that migration is not new, that people have always moved around, that mobility is a fundamental part of the human condition.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

migration in ancient Greece

Mac Sweeney, N. (2013). Foundation Myths and Politics in Ancient Ionia. Cambridge University Press.

Mac Sweeney, N. (2011). Community identity and archaeology: Dynamic communities at Aphrodisias and Beycesultan. University of Michigan Press.

Mac Sweeney, N. (Ed.). (2014). Foundation myths in ancient societies: Dialogues and discourses.. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mac Sweeney, N. (2017). Separating fact from fiction in the Ionian migration. Hesperia, 86(3), 379–421.

Mac Sweeney, N. (2016). Connectivity and Globalization in the Bronze Age of Anatolia. In T. Hodos (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Globalization and Archaeology (pp. 855-870). Routledge.