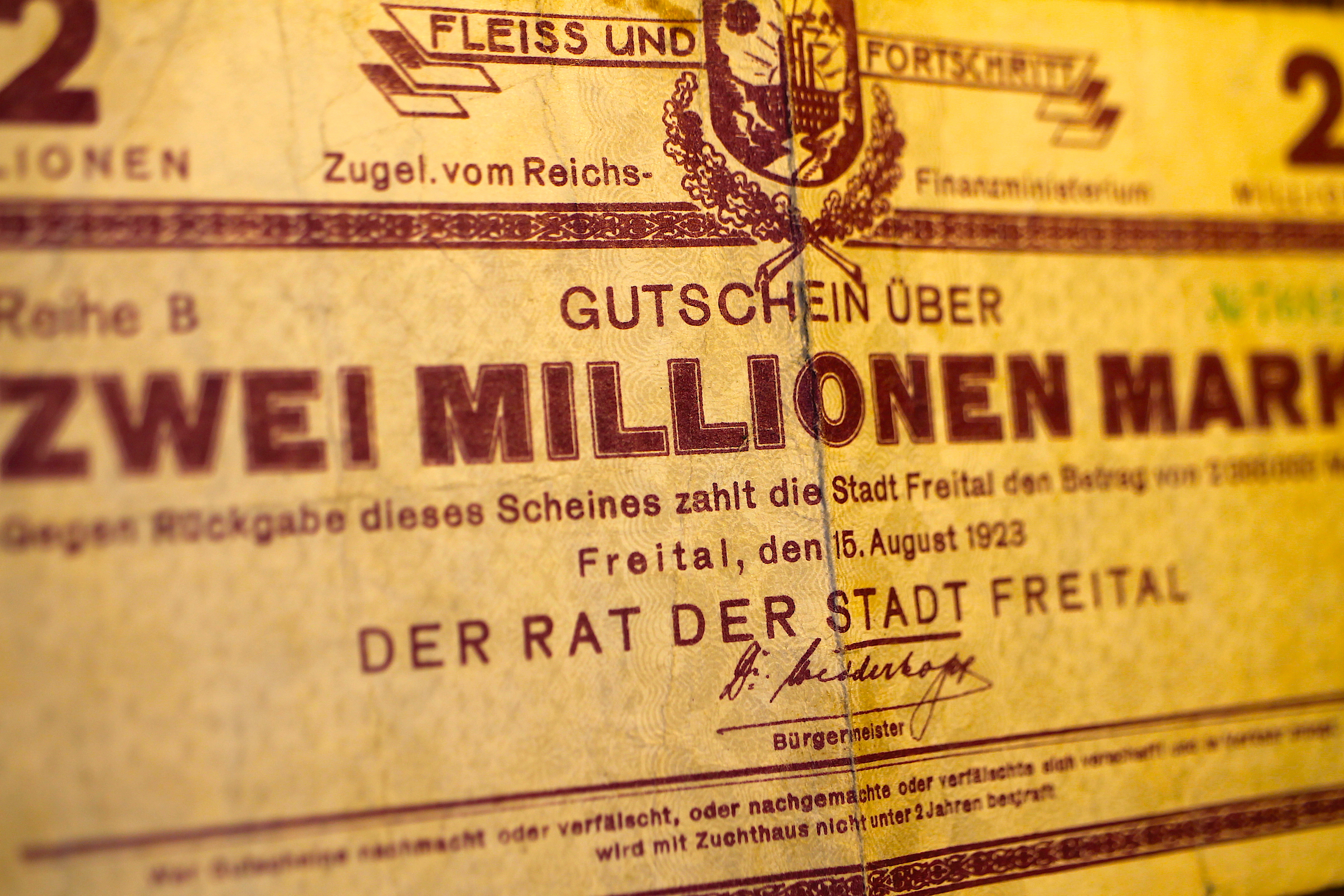

It’s very important to remember that Hitler was a fringe politician, almost a lunatic fringe, until the very end of the 1920s. So, for all his power as a speaker, as a charismatic politician and orator, he didn’t get anywhere. In 1928, the Nazis got less than 3% of the vote in the national elections. Then the Wall Street Crash happened, which spread to Europe. American banks withdrew their loans that had been propping up the German economy since the great hyperinflation of 1923, and the banks started crashing. Businesses went under. Unemployment rocketed: by 1932, over a third of the workforce was unemployed. That’s a catastrophe that brought the Nazis to national prominence. You can see their vote going up in 1930, and until the following election in 1932 they were the largest single party. Yet, it’s also important to remember they never got more than 37.4% of the national vote. In fact, they lost votes in the November 1932 elections. The two left-wing parties, the Social Democrats and the Communists combined, had more votes than the Nazis, but they were deeply divided. They fought as much against each other as they did against the Nazis.

The catastrophe that brought Hitler and Nazi Germany to power

Regius Professor Emeritus of History

- After the Wall Street Crash, American banks withdrew their loans that had been propping up the German economy since the great hyperinflation of 1923 and the banks started crashing.

- The Nazis got 44% of the vote in the 1933 elections. However, with 8% for their nationalist coalition partners, they got over the hurdle of 50%.

- They pushed through the Enabling Act, which allowed Hitler and the cabinet to make laws without referring to parliament or to the president.

- Makeshift concentration camps were established, and up to 200,000 people were imprisoned for brief periods and released on condition of not taking part in politics.

A fringe politician

Photo by Eigenblau

The Nazi campaign

People voted for the Nazi Party firstly because they offered a young, dynamic alternative to what seemed to many people to be the tired, old politics of the Weimar Republic. They promised to bring Germany out of the recession, to create jobs, to give Germany a much higher, more positive, profile on the international scene, and to recover German dignity, which the people who voted for them felt had been lost in the First World War and the following catastrophe of the fall of the Empire and the disorder and violence in the early phase of the Weimar Republic. The people felt international humiliation. The Nazis also promised to restore law and order on the streets but, of course, they themselves were responsible for a large amount of the mayhem and extraordinary levels of political violence in the early 1930s. In the elections of the summer of 1932, there were over 400 deaths – people killed in street fighting between the Nazis, the Communists and the Socialists.

Appealing to a broad electorate

The Nazis had a charismatic orator in the shape of Hitler, and they gathered to them the middle-class vote, particularly the Protestant middle classes. The existing middle-class parties collapsed; they lost almost all their support. The Nazis’ appeal was broad enough to gather a lot of votes from the working class, particularly the unorganised working class who weren’t in the trade unions or didn’t belong to the Socialist parties. They also got votes from Protestant peasants and small farmers, so from all parts of the electorate. It was the basis of being the largest party in 1932 that led Conservative politicians who didn’t have very much popular support but were backed by the president – von Hindenburg, a field marshal from the First World War, very right wing and anti-democratic – to try and co-opt the Nazi Party into supporting a revision of the Weimar Constitution in a much more authoritarian direction and to suppress the unions, the Socialists and, particularly, the Communists.

Hitler entering government

Photo by Everett Collection

Hitler was put into the Reich Chancellery on 30th January 1933, as head of a coalition government in which most of the members were Conservative politicians. These politicians were then comprehensively outmanoeuvered by Hitler and the Nazis who, within six months, had turned this coalition government into a one-party dictatorship. All the other parties had closed down or dissolved themselves, particularly the Socialists and the Communists. A raft of new laws, particularly treason laws, came through in order to concentrate power in the government. In March 1933, there were elections – a condition Hitler had made of being appointed Reich Chancellor. Amazingly, they failed to give a majority to the Nazis, who got 44% despite more or less suppressing the campaigns of the other parties. However, with 8% for their nationalist coalition partners, they got over the hurdle of 50%. On that basis, with the Communists being excluded from the parliament and the other parties, particularly the Catholic Centre Party in South Germany, being threatened with civil war, the Nazis pushed through what was called the Enabling Act on 23rd March 1933, which allowed Hitler and the cabinet to make laws without referring to parliament or to the president.

Establishing dictatorship

That kind of legal level was paralleled by massive violence on the streets. The Nazis had hundreds of thousands of armed uniformed storm troopers who went about arresting all kinds of opposition, mainly Socialists and Communists, but also Conservatives – just a few, symbolically. There was huge coercion to establish makeshift concentration camps, and up to 200,000 people were imprisoned for brief periods and released on condition of not taking part in politics. Officially, there were at least 600 murders in the camps. That’s how they established a dictatorship in 1933. We know from diaries and letters that are left that most people in the middle classes thought this would be a temporary phenomenon, that once they were in government the Nazis would be more responsible. On the left, the Communists thought this was the final, short-lived phase of the decay and the collapse of capitalism.

The Ministry of Propaganda

By the autumn of 1933, the regime had been established. A very important part of this was the creation of a so-called Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, headed by the Nazi’s propaganda leader, Joseph Goebbels. It took over the media, the press, the newsreel cinemas, music, culture, the arts and literature. It co-ordinated them all into one giant organisation, the Reich Chamber of Culture, which had numerous subdivisions and was designed to pump out Nazi propaganda. There was no independence of the press or the media after the summer of 1933. Goebbels was a propagandist of genius, not least because he realised that people didn’t want to be deluged with the message of Nazism all the way through. They wanted entertainment: popular radio programmes and fiction. So, the political propaganda was only one part of this; but, of course, there was no alternative, unless you listened to foreign radio stations, which, in due course, the Nazis made illegal – punishable during the war, even by death.

Public opinion

Photo by Everett Collection

There were no opinion polls, of course, because there was no freedom of expression, but we know about people’s opinions because the Nazis themselves monitored them very closely. However, we have numerous volumes of their reports on what people were thinking, which were conducted at a very local level and covered a whole range of issues. Furthermore, the Social Democrats had secret agents in Germany and a headquarters in Prague and then in Paris. After that, it stopped, because Paris was invaded by the Nazis, but up to 1940, we know what the Social Democratic agents were saying about popular opinion.

I think it’s important to divide popular opinion. On some issues, the Nazis were very popular. They were held to have restored the economy from the catastrophe of the early 1930s and from mass unemployment. They developed all kinds of propaganda for putting forward the idea that they were solving economic problems. They manipulated the statistics to make unemployment figures come down. Yet, in the end, what really solved the unemployment problem was rearmament: drafting young men into the armed services and building tanks and weapons of many kinds. That’s what soaked up the unemployed by 1936 or 1937, and people appreciated that. They appreciated the restoration of law and order – though the Nazis themselves had been responsible to a large extent for disorder on the streets – and their foreign policy successes.

Unpopular policies

The Nazis tried to bring the church under their wing, but the Catholic Church resisted very strongly, and openly criticised the Nazi government. Nazi attempts to reduce the influence and the power of the Catholic Church were not particularly popular. When they tried to replace pictures of the Pope on Catholic school classroom walls with pictures of Hitler, it went down very badly and they were forced in some areas, by popular protest, to stop and restore the Pope to what people regarded as his legitimate place.

When the war broke out with Poland and, as a result, in September 1939, with Britain and France as well, thereby guaranteeing Polish integrity, this was not particularly popular in Germany. An American correspondent, William L. Shirer, went around the streets of Berlin, looking for the scenes of jubilation from the beginning of the First World War, but he only saw people looking very anxious and worried.

Discover more about

The Nazi Regime

Evans, R. J. (2005). The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin Books.

Evans, R. J. (2006). The Third Reich in Power, 1933 - 1939. Penguin Books.