I know that governments, internationally, aspire to evidence-based policymaking, and I also know that scientists, internationally, aspire to having their work used by governments to do good things and serve the public good. In my experience, public civil servants are motivated by a desire to improve net social benefit. It’s a wonderful motivation, and scientists by and large would love their work to have an impact, even those who are doing relatively theoretical work.

Bridging science and policy

Professor of Risk Analysis & Policy

- A great deal of the problem is that us scientists don’t listen enough. We are too used to dispensing knowledge.

- Policymakers work in a complex environment, and scientists need to adapt to them, not the other way around.

- There’s been a growth in citizen science and their contributions of hard data.

A desire to improve

Photo by jps

A different work dynamic

There is a perception of a gap between civil servants and scientists. Scientists don’t produce what civil servants need and civil servants don’t understand the limitations of the scientists who try to serve them. Not all scientists want to serve civil servants. There are many people who want to push back the boundaries of knowledge and solve the most recent problem, find a solution or prove a theorem. They’re terrific and they should keep doing what they’re doing. There are a group of scientists at universities and other research institutions who want to contribute to public policy and, indeed, many are motivated by that aspiration. Nevertheless, there’s a gap. What we produce is often not what civil servants can use. On the one hand, the gap is caused by scientists tending to approach problems by thinking: I’ve got a set of skills on how to do this: where can I apply them? They look for a problem that already has a solution. On the other hand, civil servants say: I’ve got this problem now. I wish they’d look at my problem, because they’re not paying attention.

Listening and cooperating

Photo by l. Noyan Yilmaz

A great deal of the problem is that scientists don’t listen enough. We are used to giving lectures, talking to people and dispensing knowledge, and people often anticipate that we’ll give them what they need because we’re viewed as authority figures that will have insight and the right solution. Civil servants are clever people – they’ve been working at this for a long time. If there was an easy solution, they would have found it. They have problems that are very difficult to solve, typically problems that academics haven’t yet solved. They’re often complex problems that involve people, aspirations, values, even when they are things as prosaic as: How can I reduce my power bill? How can I contribute to reduced greenhouse gas emissions? What can I do about biodiversity?

The right pathway to an effective solution is not obvious, and it means that people that are interested in plants and animals, for example, as I am, have to start to listen to people about their personal preferences and values, their economic circumstances and their livelihoods. One might think that it’s the business of a social scientist or a psychologist, because part of the solution to this problem is beyond what I’ve been trained to do. Scientists need to seek help and they have to collaborate, because it opens the door to what is now called transdisciplinary research. We have to cooperate with people in wildly different fields to find a solution that a civil servant can actually use.

A complex environment

Policymakers are an interesting group of people. They will often create a policy in advance of the political opportunity to deploy it. I’ve had the privilege of being on the inside of some government agencies for a period of time, and seeing the cleverness with which they approach the political environment. I have seen a circumstance in which the public servants understood the need for social good, developed the policy and simply shelved it and waited for the right opportunity; when a minister was looking for an opportunity to demonstrate their investment in the environment, they had the legislation ready to go. It’s the civil servant’s job, of course, but us scientists figured that they did things in reaction mode. So, for scientists, this understanding of civil servants and the way in which they work, the way in which they negotiate this complex environment, is illuminating.

We need our work to fit their environment, not the other way around. We need to listen, understand what they want to achieve and the environment in which they need to achieve it and then provide them with a suite of alternatives that might solve their problem. But it takes patience. My work in government agencies would not have been effective had I not had mentors within those government agencies who believed we could be useful to them. Had they not opened the door, advised us, given us guidance at various stages, and protected us when things didn’t go as well as we would have hoped, the work wouldn’t have been successful. There is a need for trust on both sides of the fence. I have to trust that what they’re doing is beneficial, effective and well-intentioned, and they have to trust that I will listen, take their advice on board and try to find solutions that work for them.

The role of the citizen

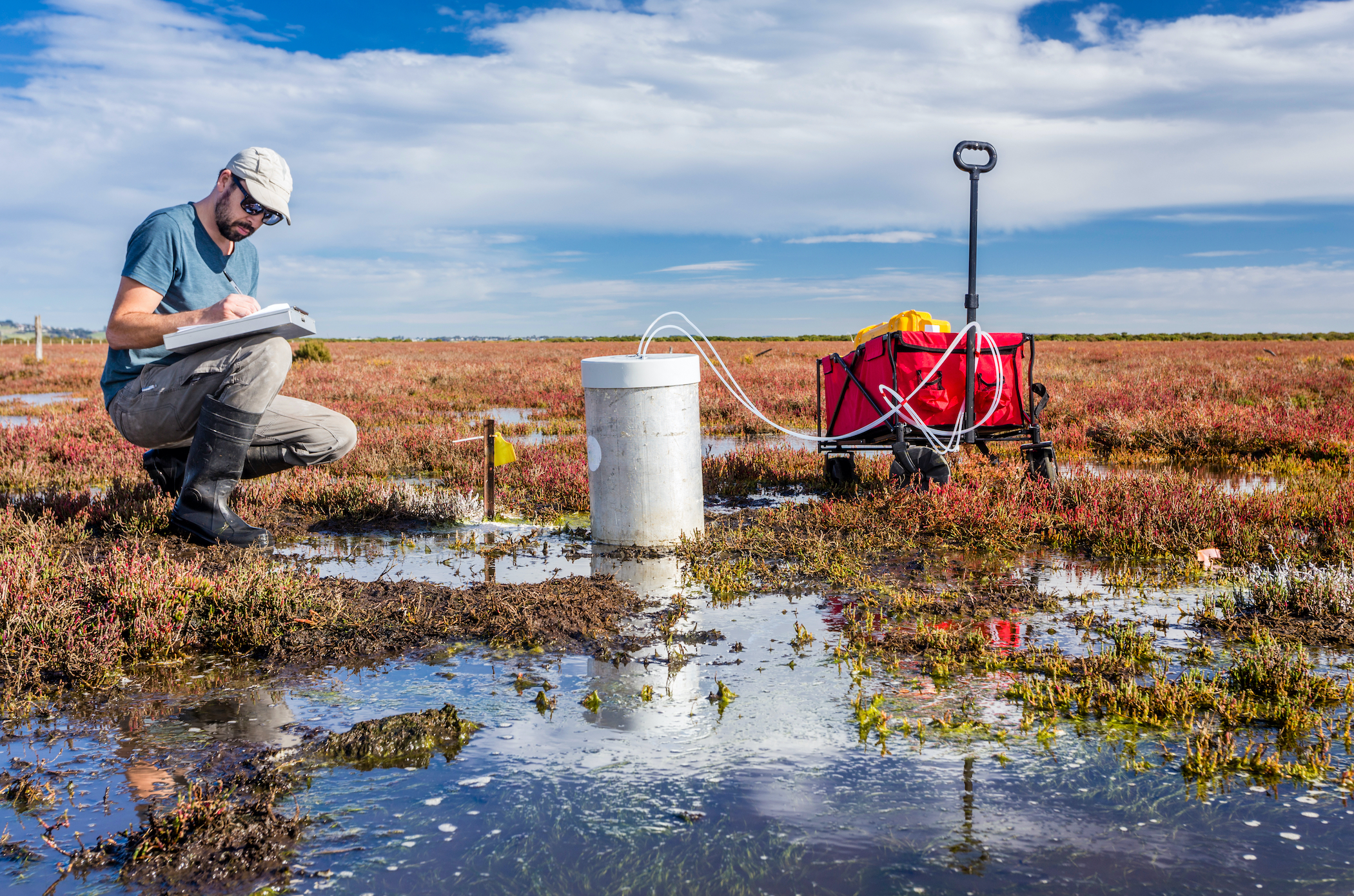

Photo by ASVMAGZ

There’s a couple of dimensions to the role of the citizen in this nexus between science and policymaking. One is how do we involve citizens in decision-making and the other is how do we involve citizens in science? Citizens can be involved at either end. The emergence of citizen science has been a phenomenon for the last 20 years. There was some resistance among scientists to this, but it’s been really interesting. A number of my colleagues thought it would benefit citizens to learn a bit about science, but questioned if they could trust the data of amateur scientists. Could they tell a badger from a wombat? The answer is yes, they could.

There’s been a wonderful growth in citizen science and their contributions of hard data to all kinds of things, ranging from field observations, which are the place where this started, through to the current evolutions of platforms online in which vast numbers of people can help scientists to work through aerial photographs, identifying penguins or other kinds of animals in the field, or looking through hours and hours of camera trap footage, looking at videos of animals and identifying and recording them. Those contributions have been wonderfully effective and have increased the reach and the ability of empirical scientists to collect and analyse data.

Structured decision-making

Structured decision-making is a way of approaching a decision that provides a gateway to ordinary people – those who may affect a decision, and those who may be affected by a decision – to be involved at all stages in the decision-making process. By that, we mean framing the problem. What is the problem? How is it phrased? The framing of the problem often constrains the subset of things that are available to us as solutions. So, thinking about how a problem is framed is a very important part of finding an equitable and effective solution. We involve stakeholders in formulating the data. What information is available to us? Where do we get it from? Who do we consult? Which models do we contemplate using? We build these models where we iterate this and stakeholders can be involved in all of these stages. There’s no reason why they should be excluded from any stage. There’s been a degree of hubris around scientists over this issue, thinking that most people won’t understand these mathematical, conceptual or statistical models – ‘They won’t know what’s going on; we’ll just tell them.’ Of course, that is wrong. It leads to distrust. It leads to circumstances in which the values and preferences of a small group of technical analysts are imposed on the rest of society – and that has happened repeatedly.

Reaching a solution

Scientists and policymakers trying to come up with a solution could be an intractable trade-off. It could be something over which they agree. At that point, it’s not a question of science or analysis: it’s a question of preferences, values and how much you’re willing to forgo to find a solution. It’s a matter of negotiation and finding an outcome that you can live with, not one that maximises or optimises anything; and if you find that solution, then it is most likely to be acceptable to most people involved. It will be robust to the kinds of things that might emerge in the future, especially if the things you’ve considered are complete, and you’ve been careful about measuring what matters. That’s part of the beauty of what’s emerged out of decision science over the last 30 or 40 years: something that was abstract, arcane and academic-seeming has developed into something that is quite useful.

Discover more about

Science and policymaking

Gibbons, P., Zammit, C., Youngentob, K., et al. (2008). Some practical suggestions for improving engagement between researchers and policyâ€makers in natural resource management. Ecological Management and Restoration, 9(3), 182–186.

Arndt, E., Burgman, M., Schneider, K., et al. (2020). Working with government-innovative approaches to evidence-based policy-making. In W. J. Sutherland, P. N. M. Brotherton, Z. G. Davies, et al. (Eds.), Conservation Research, Policy and Practice, 216–230. Cambridge University Press.

Bammer, G., O’Rourke, M., O’Connell, D., et al. (2020). Expertise in research integration and implementation for tackling complex problems: when is it needed, where can it be found and how can it be strengthened? Palgrave Commun, 6(5).