The evidence seems to be that from very early on, as we became groups (originally, we were nomads, and then we eventually settled down to doing agriculture), we began to fight each other. Some of the earliest settlements that archaeologists have found often have walls, and you don't build walls unless you have something to defend against or unless you are afraid of something. Archaeologists have found ancient graves dating millennia back that show the mass bodies of people who look like they were probably killed in conflict because their skeletons bear the marks of trauma. As far as we can tell – of course, there will always be a debate – war goes back far into human society and advances step by step with the organisation of human society.

A brief history of war

Professor of History

- War goes back very far into the past and advances step by step with the organisation of human society.

- The problem with war is that there’s a tension between trying to regulate it and the fact that it is about violence.

- One of war’s paradoxes is that it can bring social change – from the emancipation of women to important medical advances.

A definition

We use the language of war and analogies drawn from war a lot in everyday conversations. We talk about a war on obesity, on poverty and, now, we're talking about a war on pandemics. I define war as ‘organised groups applying violence to other organised groups in order to achieve their ends’. As the great German theorist of war, von Clausewitz, said: ‘war is an act of violence to compel our enemy to do our will’. I think we shouldn't lose sight of that. It's both the organisation and the violence.

War goes back very far

Photo by Ekaterina Khudina

Changing history

Wars have definitely changed the course of human society. We can see what a difference it would have made if the Persians had defeated the Greek Confederation. For example, would southern Europe have been much more Persian? We don't know, but it's quite likely. If the Ottoman Empire had managed to defeat the Austrian Empire in the 17th century, would the heart of Europe have become Muslim? It’s quite possible. Much more recently, we have had to ask ourselves: what would have happened if the Axis powers Germany, Italy, Japan and their smaller allies had won the Second World War? We would be living in a very different world, in a very different sort of society.

Limiting the cruelty

Throughout history, wars have been an act of violence, involving great cruelty. At the same time, there have been attempts to limit that cruelty, and there've been attempts to set up laws of war that try and mitigate some of war’s awful consequences. For centuries, different societies around the world have developed rules about how you treat civilians: whether or not it is legitimate to treat them as prizes or treat them as objects of war. There have been rules for centuries about how you treat prisoners of war, and sometimes those rules are obeyed. There have also been rules about when you fight and when you don't. The Greeks, for example, didn't fight each other when the Olympics were on. In the Middle Ages, at least the church in Europe tried to impose peace on holy days. It was considered illegitimate, wrong and against the laws of the church and God for people to fight on days like Easter or Christmas Day. Thus, the attempt to try and regulate and control war goes back probably as far as war itself.

When discipline breaks down

The problem with war is that there’s a perpetual tension between trying to regulate it and the fact that it’s about violence, and you see the same tension in those who fight wars. Armies can develop, for example, very disciplined soldiers who will obey orders, but you're encouraging those soldiers to go out and be killers, and sometimes discipline will break down. I think the worst horrors of war often happen when the soldiers or the sailors or, increasingly, aviators lose the discipline that has held them together and begin to run amuck, slaughtering indiscriminately. We know that that can happen in war, particularly, of course, if there's a feeling of revenge. The My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War demonstrates this: the American troops who carried out the appalling massacre in a Vietnamese village felt they were avenging fellows who had been killed in earlier attacks by Vietnamese soldiers. There's always a danger in war that discipline will break down, and people who’ve been trained to kill will begin to kill indiscriminately.

Women in war

Photo by Everett Collection

Women play a particular role in war. Although they do not fight nor have they been expected to fight in the past, they've often been used as the excuse for war, pinned as part of the reason for fighting. Soldiers have often said: ‘We are defending our women, we must fight’.

Women have sometimes encouraged war. They’ve sometimes been the cheerleaders for war. Nevertheless, of course, they've also been the victims of war. They are not usually armed. They are civilians. They are the prey of victorious soldiers, and one of the most appalling things that happens in wars is when the victorious soldiers run out of the control of their offices and begin to attack women and civilians. However, women perhaps pay a special price. They're often captured as prizes to be made into slaves or to be parts of the establishment of the victorious men.

Rape has been prevalent in war. We know that happens and we know that in some cases the officers even encourage their soldiers to rape the defeated and defenceless women, saying that it's a prize. Rape has also been used in war as a weapon. In the Bosnian War in the 1990s, for example, Serb nationalists deliberately raped Muslim women to break the Bosnian Muslims will to fight. The Serbs would say to the Muslim women: ‘You will one day have to bear a Serb child’, which was a callous thing to say. It was a way of trying to undermine the identity and the cohesion of the Bosnian Muslims. Therefore, women suffer in particular ways during war, but they also suffer as civilians, more generally.

Positive outcomes for women

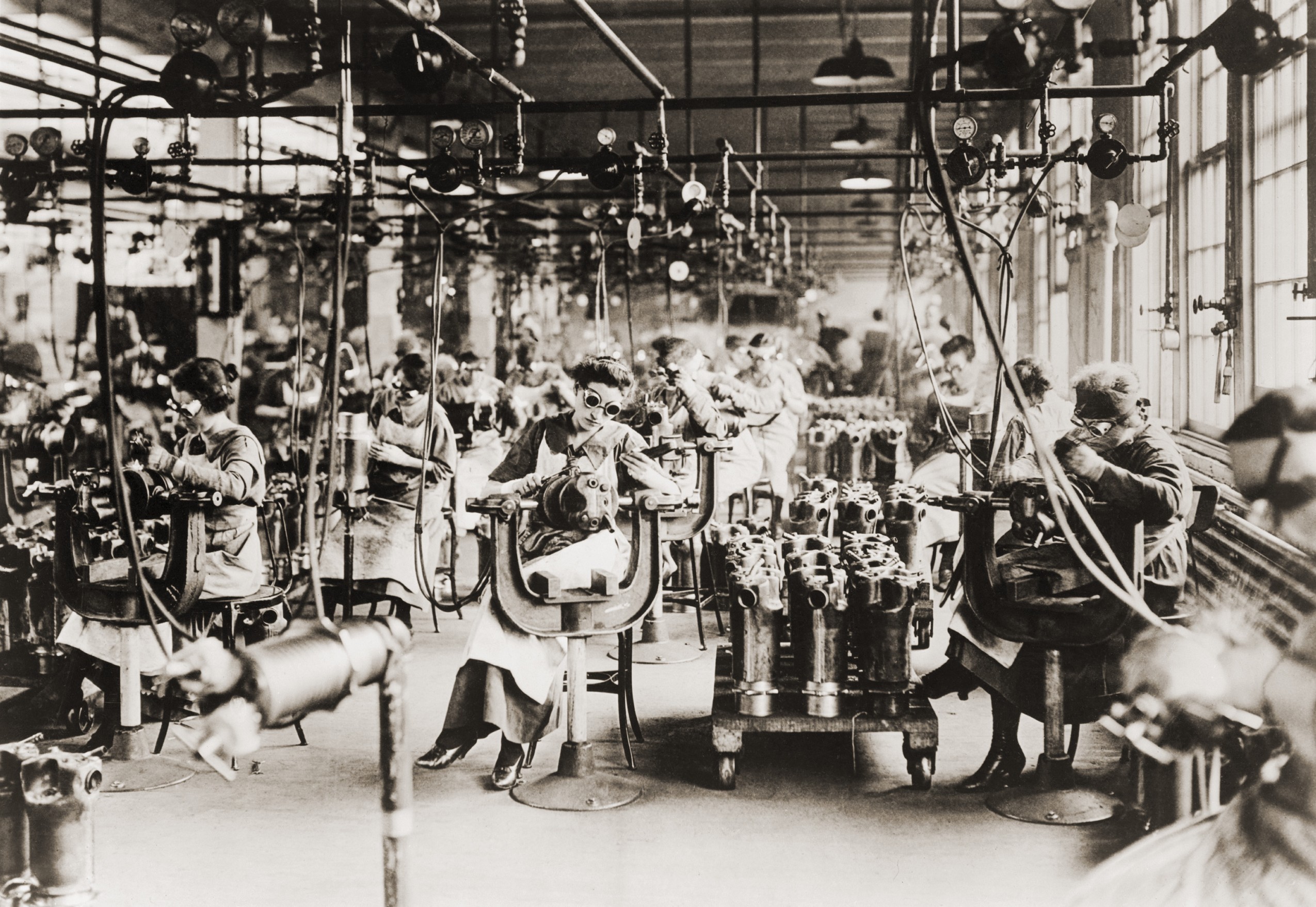

One of the great paradoxes – and there are many paradoxes about war – is that it can bring social change, the type of change that we tend to think is good and progressive. It is certainly not a myth that the position of women has improved as a result of certain wars. The two world wars made a real difference to the position of women in several societies in the 20th century. In the First World War in Britain, for example, as the men went off to fight, there were all sorts of jobs and roles that men had traditionally held that had to be filled, like jobs in factories, in offices, on farms, and women stepped up and filled them in.

It had been said often before the First World War that women were not capable of doing such jobs, that women were not capable of the hard work that was involved in, perhaps, working on a factory assembly line. What women's participation in the war showed was that women were capable of doing those sorts of jobs. Moreover, I think the government in Britain, which had been reluctant to give women the vote before the war, recognised that it was time to acknowledge the part that women played in society during the war. Subsequently, even before the First World War ended in January 1918, the British government brought in an act to give women over the age of 30 the vote, which was a direct recognition of the part that women had played during the war.

Changes in warfare

One of the big changes in modern warfare came with the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, which started in Europe and then spread around the world. What that meant was a couple of things: first of all, it was possible to produce weapons on a much larger scale than had been previously possible, so instead of someone sitting in a workshop and making a gun, you now had guns pouring off assembly lines with interchangeable parts. Gun production went up enormously. Nevertheless, the Industrial Revolution was also a scientific and technological revolution. Over the course of the 19th century, you got much better steel, much better explosives, and so by the end of the 19th century, on the eve of the First World War, the ordinary infantry gun was firing much further and much more accurately than it would have fired one hundred years prior.

A war of stalemate

Photo by Everett Collection

By the start of the First World War, you also had the internal combustion engine, which made motorcycles and trucks possible. You had the steam engine, which made it possible to have railways, to transport all the supplies and soldiers that you needed to fight. Accordingly, the Industrial Revolution increased the lethality of the weapons available. It became possible to kill in a much more efficient way. It's a horrible way to put it, but that's what was happening. It became possible to have much bigger wars with far more men in the field because you could easily equip far more people, move them, and keep them there. Additionally, you could keep bringing the supplies they needed up to the front. This made the First World War possible. However, one of the great ironies is that this enormously advanced part of the world with this hugely powerful industry in science and technology turned on itself. It produced a war that consumed it and a war of stalemate because once they got into the field, both sides were able to beat off attacks from the other side, so the war lasted for four years. It was one of the unforeseen and dreadful consequences of the Industrial Revolution.

The unintended consequences

Wars can produce unintended consequences, and some of those consequences can be good for societies and can bring benefits in peacetime. I sometimes get into trouble with audiences for saying this because they say, ‘Are you defending war?’, and I say, ‘Absolutely not’. However, it is one of those ironies or paradoxes of war: it can sometimes produce good results. Advances in medicine have been made as a result of wars. The whole notion of triage where you try and divide the less wounded and the more wounded into different groups so that you treat people in the order of the severity of their injuries was developed on the battlefield by a French doctor. Although triage is now used as a matter of course by hospital emergency rooms or people going to the scenes of accidents, the name itself, of course, is still French.

Knowing how to do transfusions was developed as a course of battlefield injuries; improvements in plastic surgery and reconstructive surgery came about in part because of the huge demand for such surgery in the First World War, and then again in the Second World War. Drug improvements have also come about as a result of wars. Penicillin, which was discovered between the First and Second World Wars, was considered much too expensive to produce in peacetime. In war, somehow, the question of expense is never as important. Penicillin was produced and saved lives in the Second World War and has saved millions of lives since. Therefore, wars speed up the development of things like medicine or speed up the development of science and technology, and civilian society will benefit from some of those things. But, as I say, we wouldn't choose to do it that way.

Remembering the past

It’s not easy to think of ways to commemorate wars because if they're commemorated entirely as triumphs, I think that says something about the society that's doing it. It’s perhaps not a very healthy thing. I think we should remember wars. We should remember the loss. We should remember those who fought in them. We should, as we remember them, be saying to ourselves ‘let’s not do this again’. My own view is that it's better to try and remember the past than to try and forget it, even though parts of the past may be very distasteful.

Memories of the past are all around us. Take the street names and the names of railway stations like the Gare d’Austerlitz or Waterloo Station, for example. These are stations named after great battles, so they're part of the fabric of the landscape within which we move. Often, I think in our literature, in some of our works of art, these are reflections and expressions of how people reacted to wars, so I think it’s a part of our society and it's a part of who we are. Remembering war is in itself a good thing, as well as acknowledging it. This is not to glorify war – that’s always a danger, of course – but simply to encourage us to remember that these are things that have happened in the past that have helped to shape us and our societies.

Discover more about

The history of war

MacMillan, M. (2020). War: How Conflict Shaped Us. Profile Books.

MacMillan, M. (2018, June 24). It would be stupid to think we have moved on from war. Look around. The Guardian.