Opium: the game changer

In 1800, Europeans had to take out to Asia vast quantities of silver to do business, but a new commodity was being introduced: opium. Opium produced in British India was going to entirely reverse that pattern of trade. From 1500 to 1800, there is a net outflow of bullion from Europe to Asia. From 1800 onwards, there is a net outflow of bullion and particular silver from Asia to Europe, and at the centre of that is going to be this trade of India to China.

What makes the Industrial Revolution possible? What makes industrial revolution possible is, first of all, new commodities such as cotton being produced in vast quantities by enslaved people in the Americas, and new consumers in Africa, the Americas and, by the middle of the 19th century, Asia. It’s often not known that, once Britain repeals the corn laws in 1846, which is to say Britain agrees to be fed by the rest of the world, it runs a permanent deficit in its trade with Europe and with the United States.

It services this deficit through the surplus of its trade with India, selling cotton goods to India. How does India pay for those cotton goods? By selling opium to China. So, on the basis of this trade of opium to China, an entirely new world economy is built up.

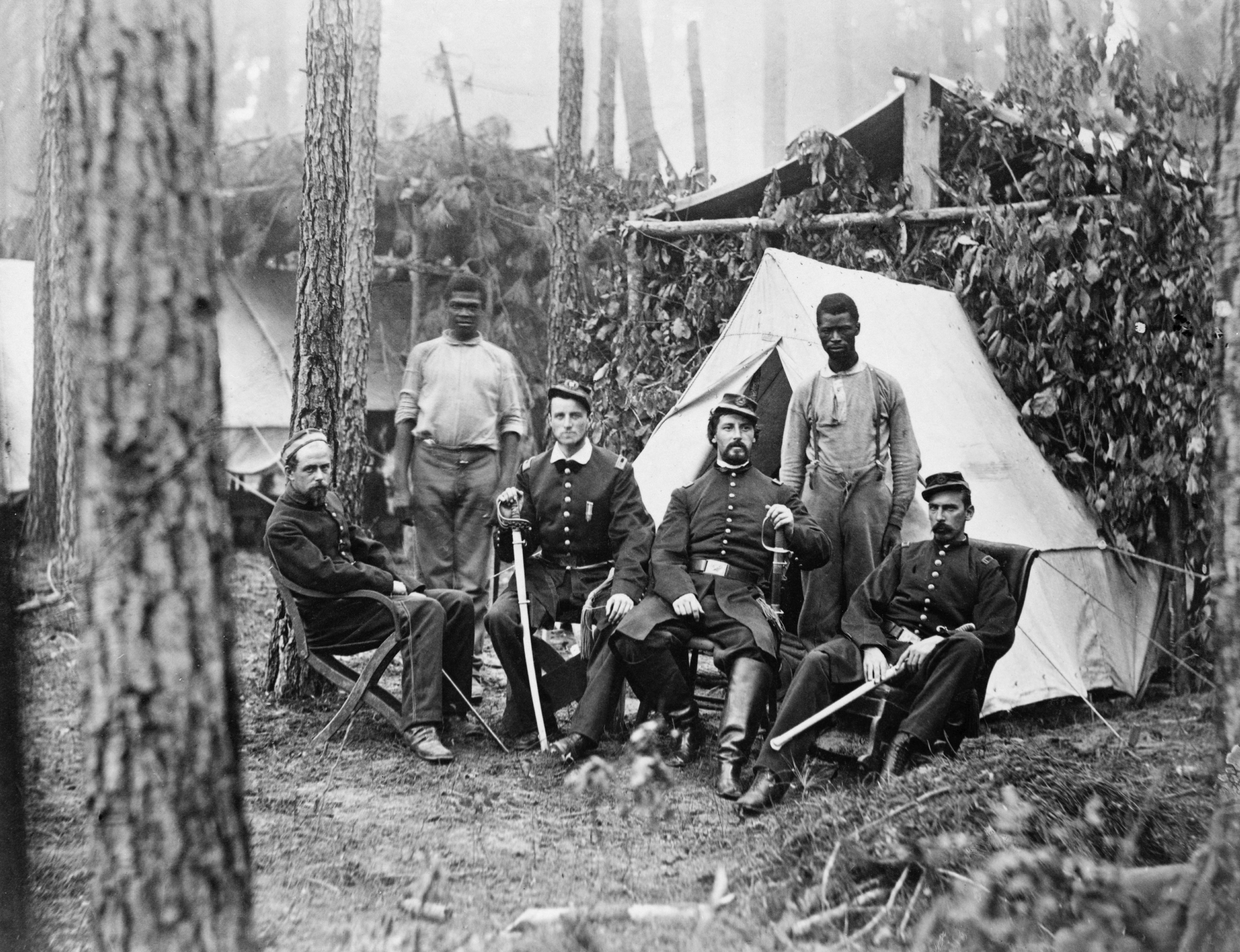

The Industrial Revolution is not just simply a question about chaps putting up factories in Lancashire or digging coal mines in the north of France. It’s about a set of global interconnections which make possible the flows of commodities and consumption, which produce this new density of industrialised interconnections, with particular extraordinary advantages within the continent of Europe. Thinking about this transformation of Asian trade, its corollary was new weapons of new warfare, with the emergence of new kinds of European imperial power.

The first sign of this was in the Opium War of 1840 to 1842, in which the British, through their gunboats, were able to impose on China access of their merchants to sell opium. This was repeated in the Second Opium War in the 1850s and with all the European powers combined, in what the French historian Pierre Singaravélou calls, “World War Zero”. It is the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in China, in which these great coalition armies combine to humiliate China – once the greatest power in the world, to which Voltaire looked with admiration – into becoming a territory divided into European spheres of influence.

The world in 1750 has changed dramatically by 1900. In Africa, we have these toeholds of European trading influence being turned, with the abolition of the slave trade into centres of European legitimate trade, and becoming very quickly enclaves of European colonial expansion. The British start by taking Lagos in 1861; 40 years later, they would be in command of the Niger Delta and the hinterland of Nigeria.

Historians commonly call the second half of the 19th century the period of high or classical Imperialism, but it’s very much a consequence, firstly, of these early connections from 1500; and secondly, of the dramatic acceleration of technological, economic and military change which follows industrial production – all of which is producing this dramatically different world in 1900, in which world business is conducted from the cities of Europe and the United States.

It is worth thinking about the psychological and cultural impact of this dramatic changing in the world balance of power. The Roman historian Tacitus puts a very interesting speech into the mouth of an ancient Briton in his book The Agricola. He says: Proprium humani ingenii est odisse quem laeseris – “It’s in the nature of human beings to hate those whom they hurt.”

Those human beings to whom we can exert forms of terrible violence, without them being able to retaliate and to impose violence upon us, become objects of contempt. The new kinds of power which Europeans enjoyed relative to the rest of the world in the late 19th century have, as their corollary, the forms of content and hate that are the modern European racist imaginaries. If one looks at descriptions which Europeans make of Asians or Africans in the 16th and 17th, and even early 18th, centuries, the language is very different from that of even David Hume in the late 18th century, let alone late 19th century commentators.

By the late 19th century, we can find a Frenchman saying that the civilisation of a people is measured by the quantity of sulphuric acid they produce. That’s an index of civilisation which establishes one particular society and its forms of living as the benchmark against which others are then evaluated.

This political order is linked, therefore, to a psychological order which has an expression in the form of domination and reaches its apogee in the second quarter of the 20th century.

Internationalisation of political imaginaries

It’s quite common to think about the horrors which took place in Germany between 1933 and 1945 as being distinctly German problems; but we need to bear in mind that their corollary was the construction of segregation in the United States in its modern forms, the creation of extraordinarily violent segregated societies in Africa and forms of encoded racialised inequality in South American societies. The Holocaust was only the extreme example of a particular turn which the West had taken from c.1900. In the midst of all this globalisation from above, through these systems of domination, there were also dramatically new kinds of interconnection being formed from below.

What we have side by side in the middle of the 19th century is the creation of an effectively Pan-European system of domination and the emergence of Pan-African, Pan-Asian, Pan-Islamic forms of internationalisation of political imaginaries.

Shifting tensions

When we come to the 20th century, we have a world which is very much in economic, political and military terms dominated by Europe; but it’s a world in which there are new forces surging from below, new ways in which communities within colonial societies who were importing from Europe not just their manufactured goods but also their ideologies and refashioning them to local purposes in India, China, Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America. They were also imagining themselves not just as participants in this form of cosmopolitan citizenship, which Europe was claiming for itself, but also as having special affinities with those near them who they understood in new terms as belonging to quasi-national communities and new kinds of regional and transnational identities.

When we come to that great crisis of 1914 to 1945, described by A. J. P. Taylor as “the wars of the British succession” – wars which were fought to decide which of the powers would preside over this system of world domination and exploitation – we see the creation of two great coalitions with a European focus which are usually thought of as simply coalitions within Europe, but really are global coalitions.

The price of victory in these great wars and the price of this mobilisation within the extended spaces of Britain, France and the United States were new kinds of tensions within that unequal order. Those who had fought on behalf of the collective interests of humanity, as they were told they were doing in these world wars, were not content to accept the subordinate status within which they had been inserted c.1900.

When we come to the aftermath of the Second World War, we are looking at a period of dramatic change on every continent. As within Europe, working people who had previously been either denied the vote or kept at the margins of their political society come to claim the centre of politics in Britain and France and elsewhere. It’s also true that in South Asia, China, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, there are new social forces moving which are going to be demanding a more equal world after 1945. At the same time, in the background, the previous beneficiaries of that unequal organisation – the world – would seek to find new ways to perpetuate their unequal share of the world’s product.