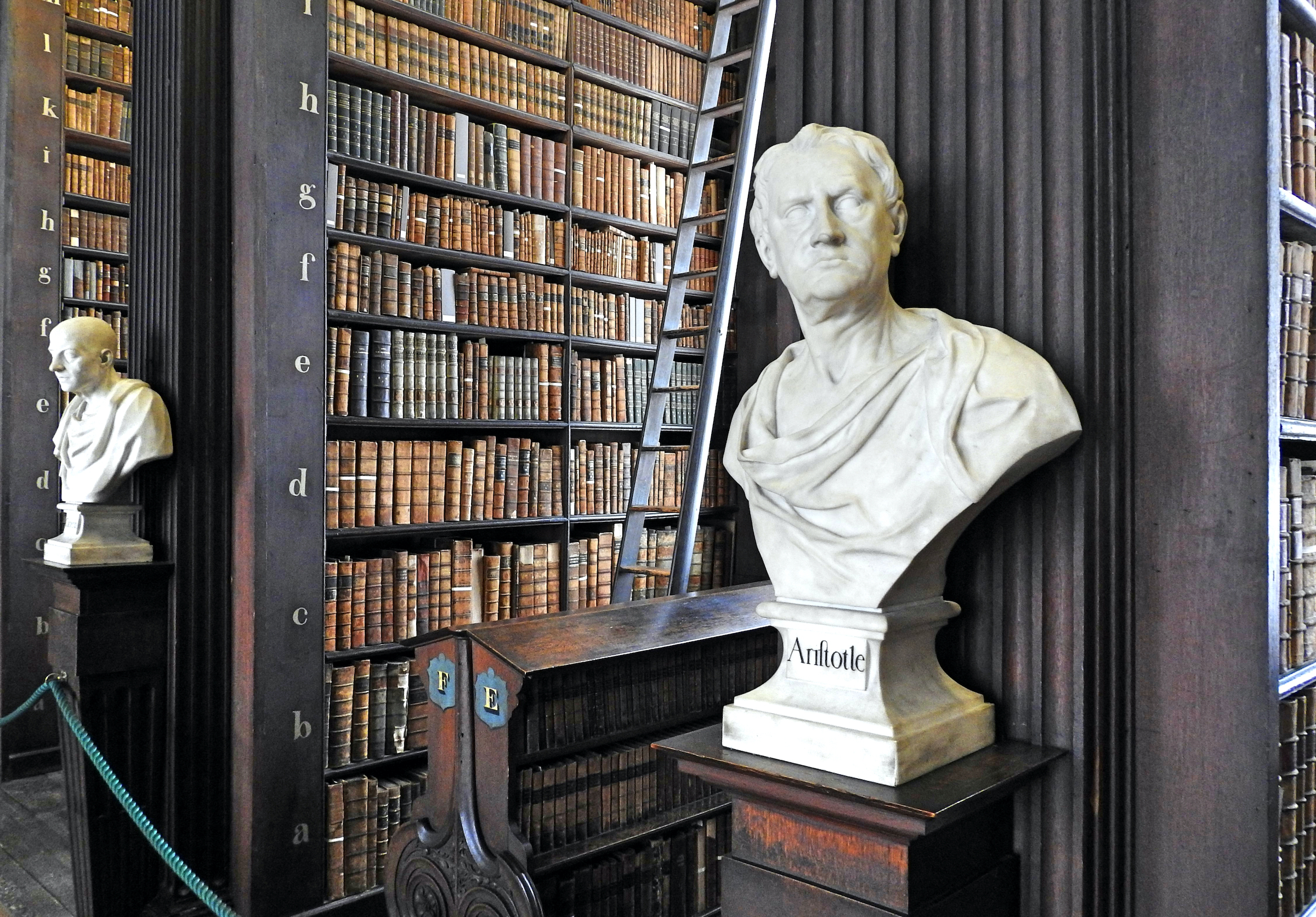

Aristotle was one of the two great founders of the entire Western philosophical tradition. He was taught by Plato – who was really the founder – absorbed everything Plato had told him and then developed it in numerous fascinating and subtle ways, also in ways that I think are much more relevant to the 21st century.

He was the greatest intellectual of all time because he was as equally interested in natural science as in what we call the humanities and philosophical subjects, but what interests me most is that he founded ethics. That is the fully developed philosophical inquiry into how we should behave and how our behaviour will affect our psychological state. Plato only thought about that from the point of view of the top down, so he invented an ideal republic. The actual well-being and behaviour of the citizens as individuals is very much secondary to the total organism. Aristotle took it the other way around and started with the human being, the individual, and worked outwards and upwards to how the whole community would look.