Malaria, a global health scandal

ICREA Research Professor

- Our first priority should be to achieve zero malaria deaths, i.e. to eliminate malaria deaths. Eliminating malaria means interrupting its transmission in a given geographic area. If we do so, it will be a huge public health gain.

- Fighting against a disease is an expensive endeavour. To adequately tackle and eventually eliminate this disease, it has been estimated that we need to double or even triple the amount of funds that we are spending today (US$ 3.1 billion).

- While the last decade has seen unprecedented progress in the control of malaria, today, for the first time in 10 years, the scientific community is concerned about an upswing in the number of cases of the disease reported in various parts of the world.

- Nearly 500,000 deaths and more than 200 million cases should not be occurring, for the very reason that malaria is an easy disease to prevent. This is a scandal. We have no choice but to solve this major global health crisis.

Zero malaria deaths

Our first priority should be to achieve zero malaria deaths, i.e. to eliminate malaria deaths. If we do so, it will be a huge public health gain. For that, we have the right tools and if we are able to take them to those who need them most, we will be able to diagnose, treat and prevent malaria.

There’s been a big dichotomy between control of malaria – how do we deal with those cases that are clinically visible – and elimination of malaria. Eliminating malaria means interrupting its transmission in a given geographic area.

Back in the 1950s, the World Health Organization put together a malaria eradication campaign which meant trying to eliminate malaria from the entire globe; this was considered by many a failure. However, it can also be seen as a partial success because it did manage to eliminate malaria from many countries.

A new impetus

Today, there is a new impetus, which goes back to 2007 when Melinda Gates, together with her husband Bill Gates, challenged the global health community to eradicate malaria.

It was judged morally unacceptable that with the tools we had and under the remarkable successes achieved in the fight against malaria during the first decade of the new millennia, we, as a global health community, were not trying hard enough and not being sufficiently courageous to attempt a global elimination approach.

For a disease that doesn’t yet have a vaccine being utilised, and that potentially has an animal reservoir, we might think it would be rather difficult and audacious to try to eliminate malaria from the face of the earth.

In fact, smallpox is the only disease to have been eradicated in human history, but for this disease a highly effective vaccine was available. And we know how difficult that was.

But with the tools that we have today, we could significantly advance and reduce the transmission of malaria to a much smaller portion of the world.

The funding challenge

Fighting against malaria is an expensive endeavour. Beyond the biological challenges and the coverage challenges, it is very clear that we have an important financial challenge.

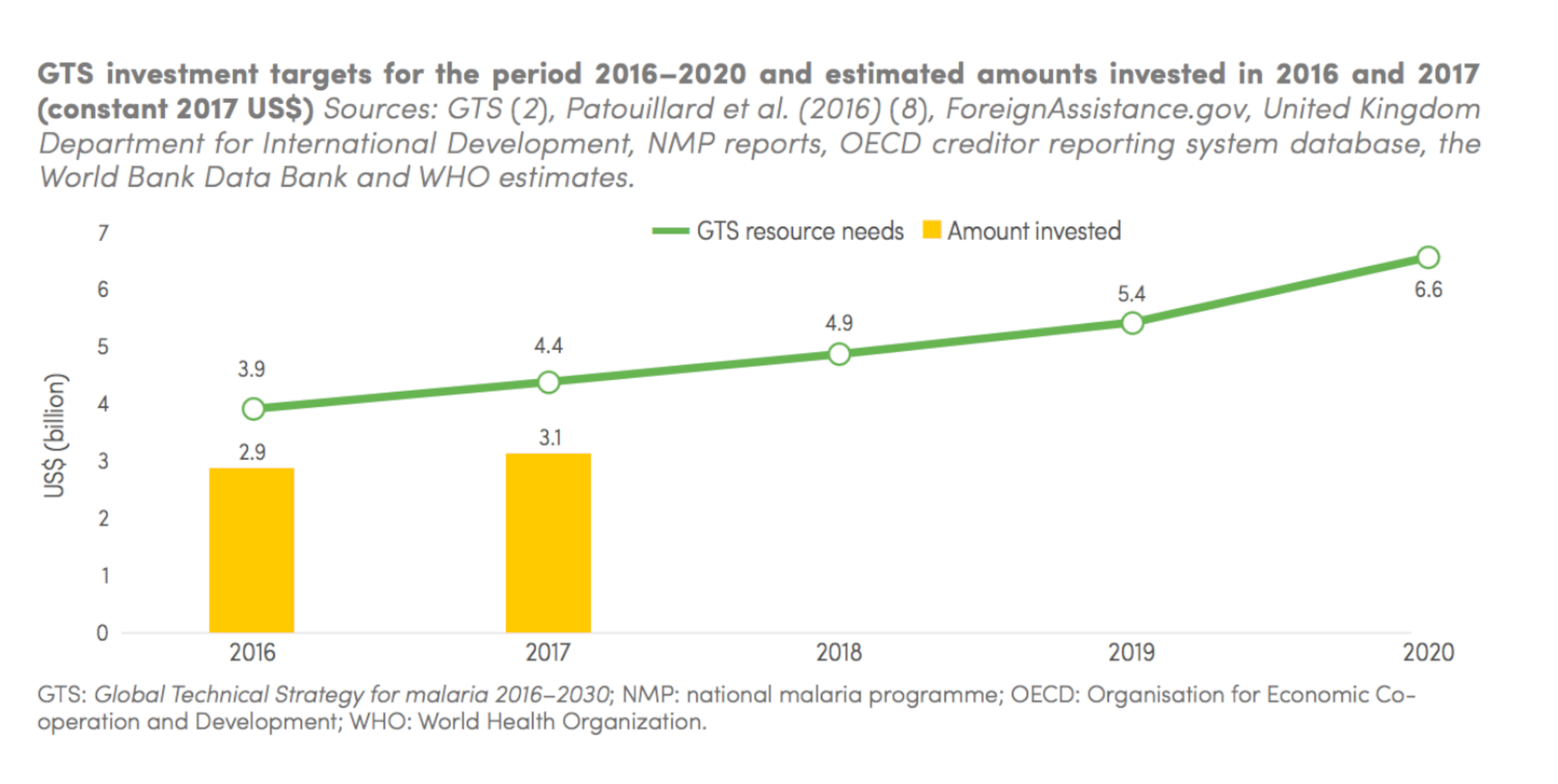

Although in the last 15 years there’s been an increasing amount of funds devoted to fighting malaria, this funding has plateaued in recent years, reaching less than half of the 2020 funding target.

Total funding for malaria control and elimination reached an estimated US$ 3.1 billion in 2017. Contributions from governments of endemic countries amounted to US$ 900 million, representing 28% of the total funding.

To adequately tackle and eventually eliminate this disease, it has been estimated that we need to double or even triple the amount of funds that we are spending today.

The global fight against malaria is at a crossroads

While the last decade has seen unprecedented progress in the control of malaria worldwide, today, for the first time in 10 years, the scientific community is gravely concerned about an upswing in the number of cases of the disease reported in various parts of the world. The upswing is worrying not only because it represents a return to the number of cases reported in 2012, but also because it has occurred simultaneously in around 25 countries situated in a variety of different geographical locations. Another significant datum is the year-on-year increase in autochthonous cases in 11 of the 21 countries currently committed to the goal of completely eliminating malaria from their national territory by 2020. In the words of Dr Pedro Alonso, head of the World Health Organization’s Malaria Control Programme, “The global fight against malaria is at a crossroads.”

The future of malaria is uncertain. In fact, the fight against malaria is at a crossroads.

We know that if we don’t increase our efforts, malaria will always come back with a vengeance. We’ve seen that in the past in many situations. On the one hand, we need to strengthen our efforts in those places where malaria remains a massive problem. On the other hand, we need not to relax and to do our work until the bitter end. It is not sufficient to bring down the numbers rapidly unless we actually bring those numbers down to zero.

The problem with malaria is that it doesn’t affect the rich part of the world and remains below our radar. If malaria was being actively transmitted in Washington or in Paris, it would very quickly become a problem of the past, because there would be a much greater investment to find the right solutions and to deliver the necessary response.

Unfortunately, the fear of malaria occurring in western countries could spark a much more proactive response globally than the one it is having today.

A vicious circle

Malaria is the perfect example of the inequities and health disparities in the world, and of the vicious circle that gets established between disease and poverty.

If you are sick from malaria, you don’t generate revenue. If you are poor, you are more vulnerable to becoming sick again. We have no choice but to break this vicious circle and turn it into a more virtuous one, a more positive one.

The malaria scandal

As a clinician, as a researcher, as a member of the global health community, my role is to fight this complacency and to try and shed some light on this invisible disease.

Nearly 500,000 deaths and more than 200 million cases should not be occurring, for the very reason that malaria is an easy disease to prevent. This is a scandal.

How can we expect malaria-endemic areas to thrive if we are not capable of lifting such a heavy burden from their shoulders.

We have no choice but to solve this major global health crisis. Let’s try to apply what we already know to solve the malaria problem. Once and for all.

Discover more about

eliminating malaria

Rabinovich, R. N., Drakeley, C., Djimde, A. A., et al. (2017). malERA: An updated research agenda for malaria elimination and eradication. PLoS medicine, 14(11):e1002456.

Alonso, P., & Noor, A. M. (2017). The global fight against malaria is at crossroads. The Lancet, 390(10112), 2532–2534.