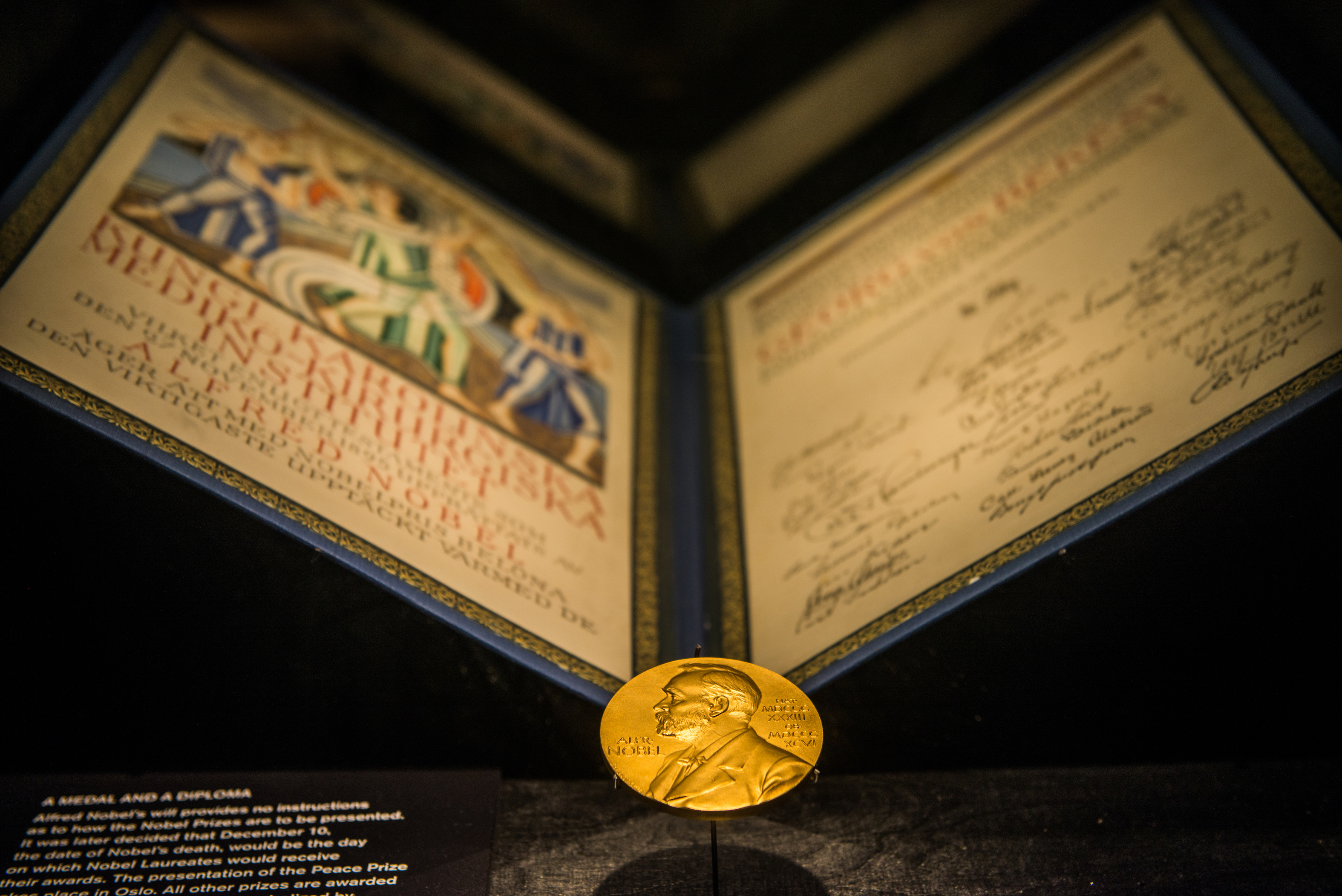

Most people would agree that the classic definition of excellence in science is making discoveries, which will then be published in classic journals such as Science or Nature. This would lead to success in obtaining competitive funding for your research in the form of grants, career progression in the form of a prestigious professorship, acquiring a number of honours, election to the Royal Society or the National Academy of Sciences and picking up a number of medals or prizes along the way – a Nobel Prize would be the pinnacle of prize-winning, but there are others. In achieving recognition from your peers, you might be asked to chair an advisory group to advise the government on a particular topic. You might be on the advisory panel of a research centre or an institute in another part of the world. These would be the classic hallmarks of excellence, from my perspective.

What do we mean by excellence in science?

EMBO Director

- The classic definition of excellence in science is making discoveries which will then be published in important journals, obtaining funding for your research, a prestigious professorship and receiving a number of honours and prizes.

- Publishing your work is important because if you keep it to yourself, the field will not move forward.

- An excellent scientist is one who cares about the results and who exhibits some humility in the way they describe their science.

The classic definition of excellence

Photo by superjoseph

A source of frustration

To publish in a journal like Science or Nature means that you’ve had to compete against a very large number of people to gain space in that journal. When I was a younger scientist, not getting my papers into those journals used to literally make me weep; yet, ultimately, the important thing has always been that an experiment isn’t really finished unless it’s published. As my lab expanded, I would keep my tears and frustration to myself and I would say to the younger members of my lab: ‘It doesn’t matter. Your career is not destroyed because you haven’t published in that journal. We need to publish it. We need to be proud that this is an excellent piece of work, and although it’s not been judged excellent by this criterion of where it’s published, we know that it’s right and we know that it can push the field forward.’

Different ways of sharing information

Publishing your work is important because if you just keep it to yourself, nobody will know what you’ve discovered and the field will not move forward. Of course, now, there are so many different ways to share the information that you’ve discovered that defining excellence by which journal you publish in is old-fashioned.

One of the things that has been remarkable over the last years with the COVID-19 pandemic has been the reliance on sharing data in the form of preprint servers. That’s where you say: ‘This is what we’ve discovered. We will subject it to review by peers anonymously, but for now, we would like you to see this information.’ There are a number of platforms where that has happened. The two that I’m associated with are bioRxiv and medRxiv.

Historically, there has been a resistance to preprint servers because people have said: ‘That’s cheating. You’ve just posted what you’ve discovered. We don’t know if it’s right or not because it hasn’t undergone this process of anonymous assessment.’ Accelerated by the need to share information really rapidly, it’s made people stand up and say: ‘This is what we’ve discovered. We may have to refine it based on other people’s comments, but do you know what? You don’t need to comment anonymously. You can comment on this work and give your name.’ So, it changes from being a sort of competitive process to being a more iterative process.

A positive science-sharing experience

Two or three years ago, we submitted a piece of work to a preprint server which had very large data sets. We wanted to share them so that the community could use them while we went through the process of having our work published in the journal. I was really surprised to get an email from a student in California who said she chose our paper to discuss in her PhD class and gave the criticisms of the work that they had found. She then said that she had just noticed that I’d posted a revised version of our preprint, which addressed many of her comments, and she wished us good luck with publishing our paper. That was very interesting to me: by virtue of sharing the work, we had inadvertently contributed to the training of students. It was a lovely experience.

Qualities of an excellent scientist

Photo by Golden Pixels LLC

It’s important to exhibit some humility in the way you describe your science. I think it’s very dangerous if you measure your own excellence by which journals you publish in. If you’re judging your own excellence by those external criteria, you might be tempted to cut some corners. You might say: ‘Well, this discovery would appeal to this particular competitive journal, so maybe I could exert some pressure on my colleagues to get those results, because they’re a nice fit with my hypothesis.’

So, for me, an excellent scientist is one who really cares about the results. A good scientist should share the results and should not put pressure on other people, particularly people they have influence on, to shape the results. I often say to people there’s absolutely nothing wrong with being wrong. If you were wrong for honest reasons and you can correct that mistake or other people can build on it, that means you’re an excellent scientist. An excellent scientist also takes care of and shows respect for their colleagues, particularly the junior colleagues in their care.

High levels of anxiety

One of the things that is characteristic of too many scientists is anxiety about their careers. They’re anxious about whether they will get their PhD. They’re anxious about being on a fixed-term contract. In a university, they may be pleased that they’ve got an assistant professorship, but then they’re anxious about getting tenure. In fact, the anxiety goes on and on. You could be one of the top scientists in the world, but every year when Nobel Prize season comes around, you’ll be anxious about not getting that phone call. I personally don’t think that that level of anxiety is necessarily healthy. I think it’s destructive.

One of the things that I find frustrating with the young scientists in my lab is that when they’re upset about where their work is published, they’ll tell me that they will never get a job. I turn around and ask them who they know who’s been in the lab and failed to get a job. And they always tell me: ‘Well, that was last year. It’s very different this year.’ The best way for advice would be: if you can’t handle the anxiety, I don’t think science is a great career. Mainly, it doesn’t pay particularly well, and you should only be doing science for the passion, the fun, the excitement of it, not because of some end goal which ultimately may be unachievable.

Career opportunities

Careers for scientists are no longer linear: it’s no longer from PhD to professor. There are so many job opportunities out there and we have many opportunities to experience different sectors. For example, you might be able to spend time as a government adviser. You might be able to work for a pharmaceutical company and use that as a springboard, possibly back into academia, maybe into other sectors. Regulation of healthcare products is another area that is hugely important. Sometimes, we just need to step back and think it’s not a race; or, if it is a race, it’s not a linear race. It’s best to define excellence on your own terms rather than fearing failure.

More scientists in government

Photo by Photographee.eu

I truly believe that we need more scientists in government, because they understand basic concepts like risk. What does this graph show? What is the risk of leaving your home or staying at home during lockdown? What’s the risk of being vaccinated or not being vaccinated? Without that basic scientific understanding of numbers, of risk, of going to and fro to refine what is the truth through the process of doing science, those skills are unfortunately lacking in government.

One of the pluses of the last year, at least in the UK, has been to see how journalists have embraced scientists. Scientists have stepped up to the plate to do their very best to explain what is going on and to explain when we just don’t know the answers. I would like to see more scientists in government. It might not be a comfortable career as a scientist, but we need more science advisers. We need to let the science inform government policy – and that’s become very clear in the last year.

Discover more about

excellence in science

Watt, F. (2018). Mentoring the Next Generation: Fiona Watt. Cell Stem Cell, 22(4), 469–608.

Srivastava, D., Watt, F., & Daley, G. (2020). Stem Cell Research Responds to COVID-19: Deepak Srivastava, Fiona Watt, and George Daley. Cell Stem Cell, 26(6), 811–814.