If we want to understand the experience of war or the potential of what war would mean to us, it is probably not a good idea to read military planners, political leaders or famous intellectuals. Many of these people were not directly experiencing the impacts of, for example, bombing. We have a natural curiosity about what would happen if we were dragged into a devastating war with a foreign power and were subjected to enemy attacks.

Civilian suffering in war

Handa Chair of Japanese-Chinese Relations

- Civilians were indispensable to the WWII war effort, and their experiences best reveal the true impact of modern conflict.

- Total war erased the boundary between front line and home front, making every aspect of society both essential to victory and a legitimate enemy target.

- Diaries and memoirs show a grinding daily misery, from hunger to family separation, that most people today might struggle to endure.

- Despite the vast civilian suffering recorded, present-day discourse still treats attacks on non-combatants as acceptable collateral, suggesting the war’s moral lessons remain largely unlearned.

Dragged into war

The best reason to turn our attention to civilians when studying World War II is that, quite frankly, they are the ones who are most like ourselves.

© Imperial War Museums

Modern warfare's support

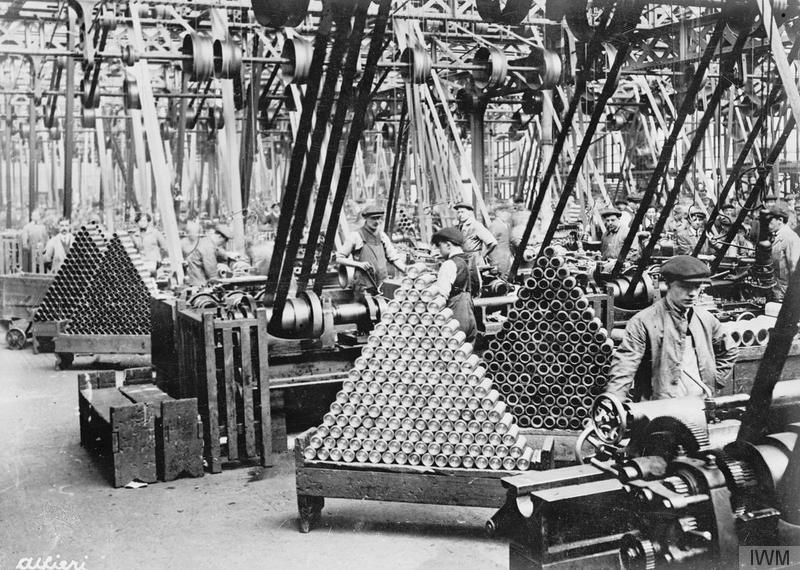

Modern warfare cannot be waged without mass support. Any power, whether it was Britain, Japan, China, the Soviet Union or Germany, required the support of civilians in order to gain victory on the battlefield. There was a lot of writing at the time indicating that new modern technologies would erase the difference between the front line and the home front, but even putting aside that very basic and obvious example of aerial bombardment, or even the fantasies around superweapons, the fact of the matter is that modern warfare depended on the productive capacities of modern societies.

© Imperial War Museums

© Imperial War Museums

The famous generals were not building the artillery shells; ordinary people were. We have to understand why they were committed, how they got committed and why they persisted, even under bombardment, to make the war machine work. How was it that people on opposite sides of a war could never connect the dots that supporting the war machine encourages the enemy to target you? How is it that these people were never able to force their leaders to stop fighting? In order to answer questions like this, which may seem obvious, even silly to ask, you need to look at the way ordinary people thought about the war — the way they wrote about it and spoke about it, what they thought was possible and what they thought was impossible. It also reminds us about what the reality of experiencing a modern war is like, because I do not think we appreciate it. Much of that has to do with the post-war myth-making that exists in every country in the world, from Britain to Russia today and even Japan. We often forget how terrible modern war was for people who had normal jobs and normal lives and lived in the cities.

Living in misery

In doing the research on attacks on civilians from the air during World War II, I came across a lot of very powerful stories from the time, and it was difficult. When you do very deep archival and comparative research, it can be a real challenge to pull it together as a coherent narrative. There were certain things that kept coming up over and over again that I thought were important for modern readers to understand. One of them was that the war years were, to put it very bluntly, miserable. You did not have treats. You could not go on holiday.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

Your parents or children could be separated from you; the cinemas could close; the pubs could close; you could not get across the city, because the transport systems were disrupted; and the overwhelming sense that you get from the diary accounts in particular, but even in the memoirs, is this grinding misery.

Lost wedding ring

For example, one teenage girl was writing in her diary about her father going to the sink to wash his hands — and this is in Britain in 1940, in the deepest period of the aerial bombardment by the German Air Force.

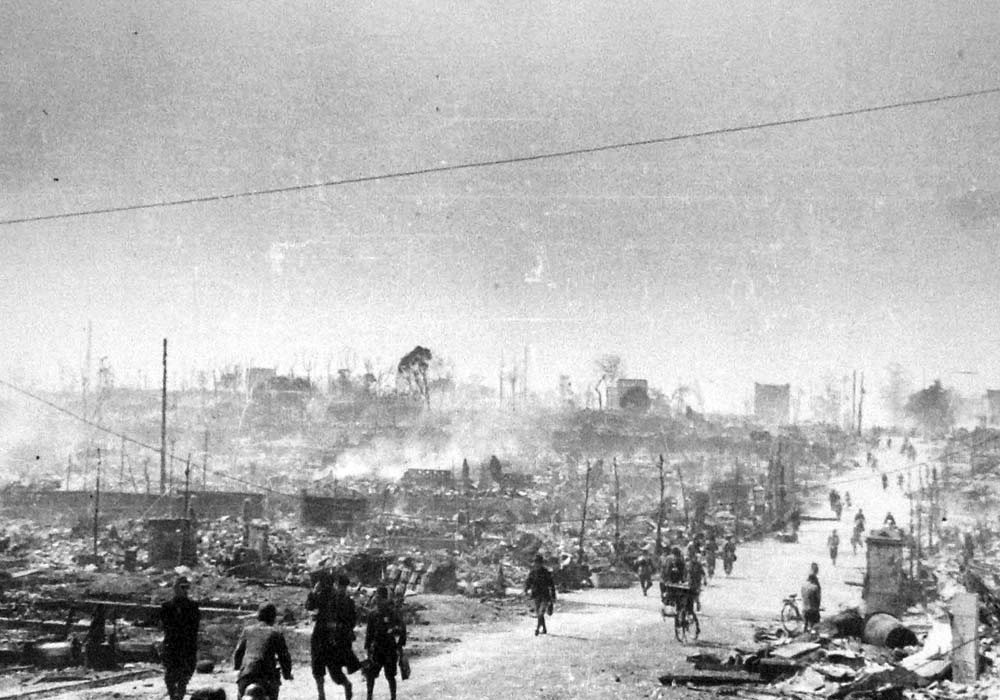

As he is washing his hands, his wedding ring falls off and goes down the drain, because he had gotten so thin from lack of food that his ring would not stay on his finger. It is those kinds of moments when you see just how miserable people were at that time. For example, in Japan, after cities were bombarded, it was often teenagers who were sent out to clear the streets, and this did not just mean pieces of rubble, plaster and wood but human bodies as well.

© Ishikawa Kōyō

© Ishikawa Kōyō

There are many accounts where they describe finding their classmates, the bits and pieces of their bodies on the roads, and how it then forces them to think about their own mortality — their missing father who might be in the Pacific — and, overall, the importance of family. It was quite striking to me that adolescents, who we do not normally associate with being very attached to their family — they often want to get away from their family and establish their independence — were really committed to keeping their families together in this sense of insecurity. When you read through 150 or 200 of these accounts in Britain and Japan, the overwhelming sense you get is that you wonder how well we would endure similar circumstances today, when people feel that if they cannot eat meat seven days a week, they are poor. The people then lived a very different existence, and I am not so sure that we would have the endurance to do it today.

A "good war"?

The Second World War is often described as the good war — but after reading hundreds of civilian accounts, I am not so sure what was good about it.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

It may have been the necessary war, and many good things came out of it in the sense that the Nazi regime was destroyed, and the Empire of Japan was destroyed, but it is hard to describe a war conducted in this way as a noble effort. I think you find that historians are fairly divided on this topic, because those of us who emphasize the importance of the civilian accounts tend to say things like, targeting civilians is never moral; it is always an immoral act. Furthermore, it did not really seem to hasten the war's end in any significant way. Historians who focus on military strategy documents and the statements from political leaders are more inclined to say the opposite and argue that, as troubling as it was, there were reasons why civilian targets were hit, often unintentionally, and that it is part of the many factors that brought about the end of the Second World War. I do not propose a definitive answer to this question, except that, according to contemporary law, it is immoral to target civilians purposefully. So, that should really be beyond question. Whether or not it hastened the end of the war, or whether the Allies were justified, for example, in targeting civilian areas, is something that historians continue to debate, and opinions are divided depending on which documents they read.

Civilian responsibility?

One of the difficulties we encounter when studying the wartime period is the problem of the necessity of public support for the war to succeed on the one hand, and how that makes us targets of the enemy on the other. Everyone surely can agree that it is wrong to purposefully target civilians; however, if civilians are necessary for the war effort — they build the planes; they produce the food; they make the railways work — the war machine in the modern era simply does not function without them.

© Imperial War Museums

© Imperial War Museums

It even goes down to very basic things like looking after children, looking after the elderly and baking the bread on a daily basis. These ordinary people are responsible. Even the weakest members of society are responsible for making modern war possible. So, how can you not target them to defeat your enemies? In doing so, you then invite the enemy to target you as well. It becomes a vicious cycle of reprisal and pursuit of total victory. This is one of the reasons why we call it a total war. It is not simply because it draws from every resource within society; it then also makes every aspect of society a target for enemy attack. In that sense, every war in the modern era becomes a suicidal war if you are a civilian.

Children's wartime perspectives

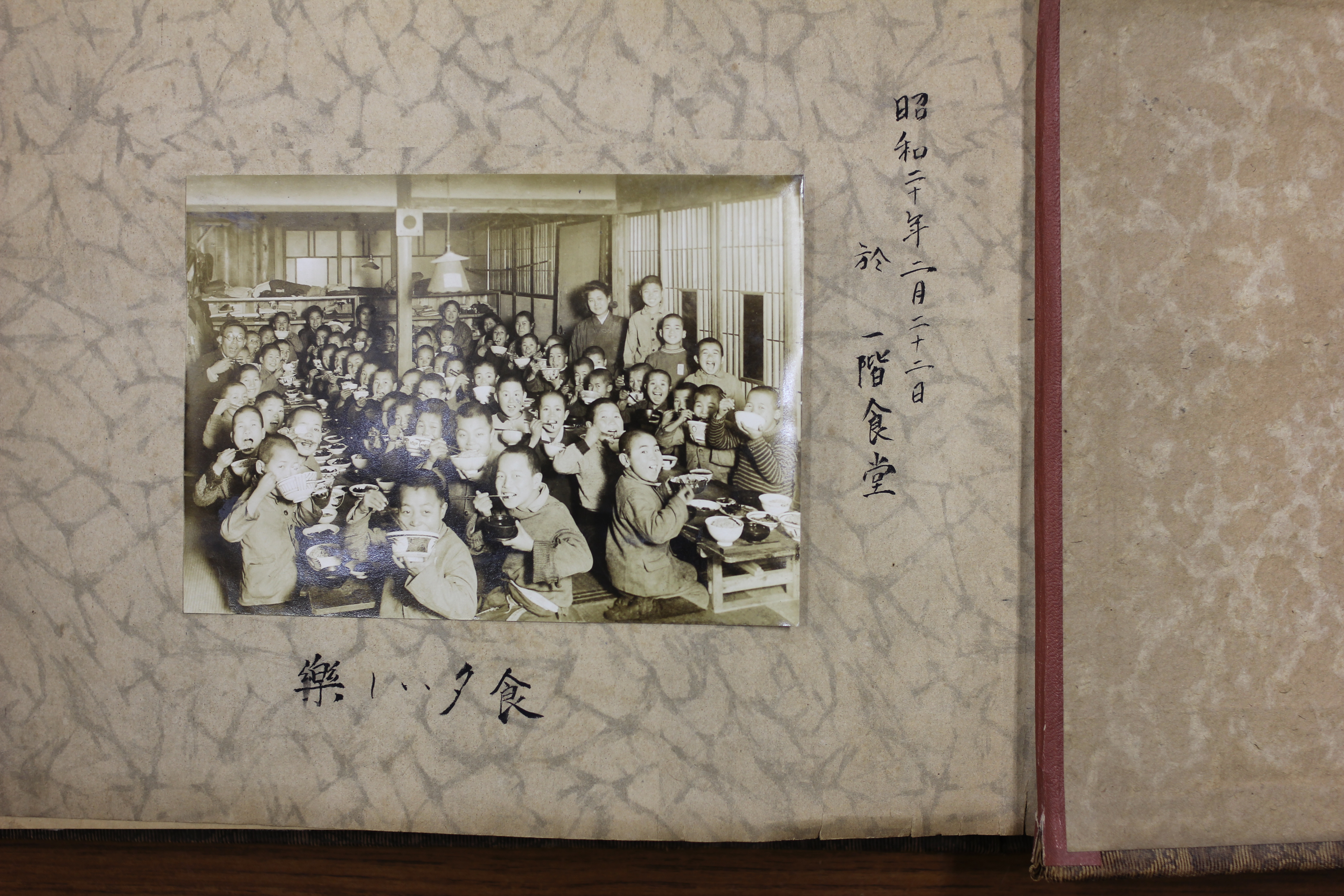

One of the aspects of the Second World War and the social experience that I have become more interested in over the last few years has been the way that children write about it — and not just children but also adolescents. Anyone aged from the time they can write and draw to roughly the period they enter the workforce, which changes from nation to nation. It is very protean and mutable, the way people define childhood. What I found fascinating, particularly about children's accounts, is that in some cases, if you read hundreds of these as I have, you forget completely that there is actually a war happening.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

The reason for this is that children have a limited vocabulary range of things they can write about. They like to write about food. They like to write about adults in their lives, like their schoolteacher. They might talk about games they play. The intricacies of the global economy, politics and military strategy are not in their repertoire of things to talk about, and that in and of itself is fascinating. It is almost as if you have encountered an alien species living in a different reality from 1939 to 1945. Who are these people that do not realize there is a destructive war going on? Of course, some children do write about this. They are hungry; they miss their parents; they get evacuated; they see bombing. These things, of course, do get written in children's accounts. I found it far more surprising and charming that you can have a nine-year-old evacuated to the countryside who spent many years of the war simply playing games and, it must be said, eating better than those who were stuck in the cities because they were closer to the farms.

War destroyed families

One of the things I discovered when reading through the civilian accounts of the Second World War was an unusual articulation, particularly among women, about their romantic relationships with men — and particularly important men in their lives, like their husbands.

One Japanese woman, Idaee Hisai, wrote about her husband: "I was pregnant when he was conscripted, and I suppressed all kinds of emotions so that I could send him off with a smile. I watched his large body from behind. So dependable, kind and sad. I can still hear the sound of his boots as he walked away."

Not far away in Hachioji, another woman, Takizawa Toki, made sure that during her husband's departure to the Pacific she did not cry in front of him when he was shipped off to the war. She sent him off with a smiling face and promised her husband before he went off to the Pacific that she would take care of things for him while he was away, but as the time came she started to lose control of her emotions. She wrote:

"At that moment, all the emotions I had been suppressing exploded, and I just cried and cried. But that was pointless. Everyone thought it was for the nation. So I had just found strength, found my resolve and thought, I am going to overcome everything for my children and my parents. My husband put his life on the line for the nation, so I have to as well. Even though we are a thousand miles apart, our hearts were one. Or so I thought, getting by day by day. Then on 5 April, 1944, my husband arrived unexpectedly. He just appeared at my bed. So I was shocked, woke my parents and spent the rest of the evening as if in a dream. The next day I went with five children to the station to see him off. I did not know that this was our final moment. I waved at him furiously until the train could no longer be seen. Going home, I was returning to my life of solitude, and the children kept saying, 'Mummy, I am hungry.'"

There is one more passage that nicely reflects this from Britain. One of my favorite writers at the time, Olive Metcalf, was in Hull, and her husband was stationed as an anti-aircraft gunner in London while she was pregnant. She wrote:

"Often I feel like a climbing plant that has lost its wall and is trying to stand alone. You cannot know how I long for your presence sometimes, just you to take over and shoulder things."

Throughout the whole period of their correspondence she talks about how much she misses him and even talks about their sexual life. I think it is one of the areas that perhaps we underappreciate — that the conscription for the war effort really destroyed many families, and the first attack on the family did not come from enemy aircraft but from their own government.

Lessons still unlearned

After I had read several accounts by civilians — children, housewives, working men — from World War II, one of the overwhelming impressions I had was the sense of loss. I do not just mean the tragedy of people dying, which is bad enough. It was the, to put it in a very crude way, opportunity cost of losing so many people. Especially when you think about young people — young men killed on a battlefield or children who were killed because of bombing campaigns or through starvation. You wonder what kind of people they would have become had we not embarked on these total conflicts. When you look at war today, where there is a disturbing trend towards justifying attacks on civilian populations — whether it is the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Russia-Ukraine conflict or any other conflict — the way in which people talk about the deaths as a compensatable loss is rather extraordinary, and it reveals an ignorance about how human society builds itself. You cannot wipe people off the map and then expect there to be no consequences. I do not mean political consequences in an election; I mean the society that these people would have built can no longer exist. That loss becomes more acute when you read the civilian accounts, because you can see the person they are becoming until the moment they are lost.

© Imperial War Museums

© Imperial War Museums

From my perspective, there is a very disturbingly cavalier attitude towards targeting civilian populations of enemy nations. It shows that whatever lesson we were supposed to have gained from the Second World War through the painstaking record — diaries, memoirs and oral histories that were transmitted and retransmitted, inscribed and reinscribed, archived and put into libraries and films and so on — that message just does not seem to have landed with us very well. Maybe there is still time to avoid these conflicts going forward, but we currently seem very eager to re-experience the kind of civilian suffering that you can see in the Second World War.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

civilians in wartime

Moore, A. W. (2018). Bombing the city: Civilian accounts of the air war in Britain and Japan, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press.

Moore, A. W. (2021). Children we have lost: Diaries, memoirs, and museum displays of childhood and youth in wartime Japan. Cultural and Social History, 17(5), 715–729.

Moore, A. W. (2016). From individual child to war youth: The construction of collective experience among evacuated Japanese children during World War II. Japanese Studies, 36(3), 339–360

Moore, A. W. (2017). Reversing the gaze: The construction of “adulthood” in the wartime diaries of Japanese children and youth. In S. Frühstück & A. Walthall (Eds.), Child’s play: Multi-sensory histories of children and childhood in Japan (pp. 141–159). University of California Press