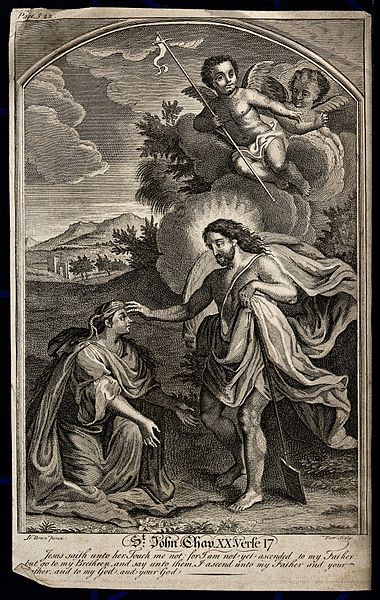

The figure who complicates this straightforward idea of a change is, of course, Doubting Thomas, who will not believe in the resurrection until he is invited to stick his finger into the wound in Christ’s side and feel it for himself. What’s fascinating about the figure of Doubting Thomas is that the desire that he expresses is both horrifying and understandable: there’s a sense of direct, unmediated, fleshly access to this divinity that it’s almost right to want, but, at the same time, this feeling that he’s doing something very transgressive. The greatest depiction of this figure that captures these two sides so wonderfully is the famous Caravaggio painting, which shows Thomas thrusting his finger into Christ’s side. The way in which Thomas’s body is depicted is amazing.

Touch: the most powerful of our senses

Professor of English Literature

- The sense of touch is represented in Christianity in a contradictory way: Christ touches people to cure them, but after he’s resurrected, he seems to hold human life at a distance.

- There are many artworks that represent touch in interesting forms. It’s also imbued in our language.

- In addition to the pandemic, it’s very difficult to think about the contemporary status of touch without thinking about the #MeToo movement and the abuses to which interaction is open.

The history and biology of touch

What distinguishes the sense of touch, historically, is that it’s had an extremely unstable status among the human senses. There have been various hierarchies of the senses at different times, but touch is distinct among them for being seen as, at different points, the highest and the lowest of the senses. On the one hand, touch is valuable because it’s reliable. If you want to know something is true, you touch it; you put your hand on it.

Also, touch is seen as biologically necessary, the sense that distinguishes animal life. This is an idea that goes all the way back to Aristotle – that there are animals that exist that lack each of the other senses. Humans can lose each of the other senses permanently and still survive, but if you permanently lose touch, you are no longer alive or no longer an animal, in Aristotle’s view. Those are reasons to value touch, to see it as necessary and reliable.

On the other hand, it is the most bodily of the senses; each of the other senses is restricted to or located in an organ, while touch is coextensive with the body. It exists throughout our body. It’s also seen as producing dangerous kinds of pleasure, principally sexual pleasure. So, you have this deep tension in the ways that people understand the sense of touch: you need it in life and for knowledge, but the minute you exercise it, you’re at risk of debasing yourself, of giving in to your body and its pleasures and desires.

An unstable status

The unstable status of touch then takes on a very distinctive and culturally significant form in the way that it’s understood within Christianity. There’s a tension, or perhaps a contradiction, in the gospels: Christ touches people to cure them; he makes himself available as an object of human touch, but, following the resurrection, when he is encountered by Mary Magdalene in the garden, the first words he says to her are, ‘Noli me tangere’ – ‘Don’t touch me’. So, the minute he’s resurrected, he seems to hold human life at a distance and to exist beyond touch, in some sense.

Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Touch in art and language

I first became interested in thinking about touch because it was part of the language that I and many other people use every day. I suppose I did encounter some of these privileged cultural scenes, like Christ and doubting Thomas. I was struck quite early on by one or two other artworks that seemed to represent touch in interesting ways. One that got me started thinking about this is Rembrandt’s painting of Aristotle with his hand on a bust of Homer, on a statue of Homer’s head, and this sense of: why would you touch a statue? You don’t enjoy a statue’s beauty by touching it – and yet we do often want to touch statues.

Jennie Gerarhdt

So, I got interested via art, but it was actually this sense that, on the one hand, there are these scenes of touch – these moments, these representations, these culturally charged instances – and on the other hand, it’s everywhere. It’s constant, and not just in our interactions with one another, with the world and with ourselves, but it’s also distributed through our language: we say ‘keep in touch’, or talk about ‘losing touch with someone’ or even grasping at an idea. It fascinates me that, on one level, touch is very bodily. It’s very physical and, therefore, at the opposite end of the standard spectrum from the rational. Yet, we seem to think of our mind as a kind of hand, as something that physically encounters the world. That combination struck me as so fascinating and full of possibility.

Galen’s view of touch

Touch plays a very important role in the history of medicine, in part because it was such a crucial feature of the physicians’ diagnostic repertoire, especially in ages where the inside of the body was so difficult to access. The physician Galen, whose work laid the foundations for centuries of thinking about medicine, wrote that the doctor had to be an expert in touch.

Galen thought touch was something that could and should be trained, for palpating the patient’s body, for working out what’s going on and especially for the feeling of the pulse. Feeling both the nature and speed of the human pulse was, for him, second only to the analysis of urine as a way of understanding what was going on inside the body.

The view of touch now?

We’re now a year into the coronavirus pandemic, and among the various aspects of life that this year has led us all to reflect upon in new ways, touch has certainly been very prominent among them. You get the sense that suddenly touch is subject to certain kinds of restriction, that it’s dangerous, in certain ways, and there needs to be enormous amounts of attention to it.

Hananeko studio

I think the implications of that have been twofold: on the one hand, it brings home how crucial touch is, almost going back to Aristotle’s very ancient idea about touch being necessary for life in a biological sense, which has been borne out of touch as necessary for humans as social beings. There have also been many studies of newborn children and the importance of touch for their survival. So, we know that touch matters, and I think that the past year will probably make those of us who’ve gone through it, value that more.

On the other hand, it does remind us, albeit in a painful, protracted and frustrating way, about how much is potentially at stake in certain acts of touch – that there’s obviously a physical danger of spreading infection. Touch is also caught up in the way that social relationships are managed, maintained and, at times, violated.

The #MeToo movement

Beyond the pandemic, it’s also very difficult to think about the contemporary status of touch without thinking about things like the Me Too movement and how that has encouraged a reflection on the ways in which people interact with one another, and the abuses to which those interactions are open.

What the Me Too movement has made very clear is that while there are straightforwardly reprehensible actions that people have got away with, there have also been many cases in which it seems like the place of touch in our social interactions can become a cover for things that can pass themselves off as innocent. So, sexual harassment will often take the form of a hand left for a few seconds too long, or placed just slightly low on the small of the back, or whatever it might be. These are things that are almost parasitical upon the routine place of touch in our social interactions.

There is a somewhat chastening and slightly downbeat lesson, which is that we are stuck with the predicament of touch being essential, valued and cherished – and also inescapably caught up in social relations, which means power relations: a way of establishing, navigating and negotiating power.

The experience of tickling

One of the more enigmatic experiences of touch, for a very long time, has been the experience of tickling. This is, rather pleasingly, also associated with the Greek philosopher Aristotle. It’s not the kind of thing we probably think of him as troubling himself with, and, in fact, he probably didn’t write the work in question, called The Problemata. It includes a series of unsolvable problems around touch, and quite a lot of them focus on tickling. The author is particularly perplexed by the fact that we cannot tickle ourselves – which, once you start thinking about it, seems very interesting, because it suggests that two physically identical experiences – fingers on flesh – are by no means experienced in identical ways. Therefore, our experiences of touch are a complicated mixture of our bodies and our minds. It brings home the intimate connection between mind and body. Every time you laugh when you’re tickled, that’s what’s coming to the fore.

Humans are sometimes called the “rational animal”, also the “laughing animal”. We laugh and animals don’t, so being “tickleable” is part of our humanity. On the other hand, tickling is, again, bound up with power. The fact that you need someone else there to be tickled, that you can’t tickle yourself, is also a reminder that the relationship in tickling is always an uneven one. Children can get slightly manic when they’re tickled, and it’s because they’re experiencing a version of adult power over them that they have to endure.

Discover more about

the sense of touch

Moshenska, J. (2014). Feeling Pleasures: The Sense of Touch in Renaissance England. Oxford University Press.

Classen, C. (2012). The Deepest Sense: A Cultural History of Touch. University of Illinois Press.

Leader, D. (2016). Hands: What We Do With Them, and Why. Penguin.