To contemporary observers from abroad, those two things seemed to go together – and I think they were right to link them. The freedom came partly from England’s own bloodless political revolution in 1688, when it kicked out the absolutist, or would-be absolutist, monarch James II and replaced him with a pair of constitutional monarchs, William and Mary. More extraordinary, in a way, was what happened in 1695, when, almost by accident, England gained itself freedom of the press. That was when the Licensing Act, which governed printing and publishing throughout the country, lapsed.

The 18th century novel: commercial and cultural buzz

Professor of English

- After the Licensing Act lapsed in 1695, anyone with the capital and entrepreneurial spirit to set up a printing press could do so. Literature then became something that got bought and sold.

- Having noticed the fashion for travellers’ tales, Daniel Defoe published Robinson Crusoe in 1719, which is regarded today as the first proper novel in English.

- Published in 1740, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela marks the beginning of the rise of the novel. With its moral earnestness, it makes fiction respectable.

Freedom and commerce in 18th century London

Foreigners who travelled to England, and particularly to London, in the early 18th century noticed two things. The first was the extraordinary freedom of the place compared with the countries they came from. The second was the commercial buzz. There were shops and people doing business everywhere.

18th century print of London customs house. By Bowles and Carver. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Literature for sale

Previously, there had been a very strict limit to the number of printing presses that were allowed. After the Licensing Act lapsed, there was a kind of free for all. Anybody could set up a printing press if they had the capital and the entrepreneurial spirit to do so.

The laws governing what could be printed and published were remarkably lax. As long as you stayed this side of what was called “seditious libel”, which was basically arguing that the monarchy should be pulled down, you could get away with almost anything. So, the freedom wasn’t just in the eye of the beholder; it was a real freedom, and in particular, it was freedom of the press.

That gave a huge commercial impetus to the business of publishing, printing and finding new forms of print. The early 18th century wasn’t just a great age of satire, which was liberated by this kind of new freedom. It was also a great age of journalism – newspapers, periodicals, pamphlets and, eventually, magazines.

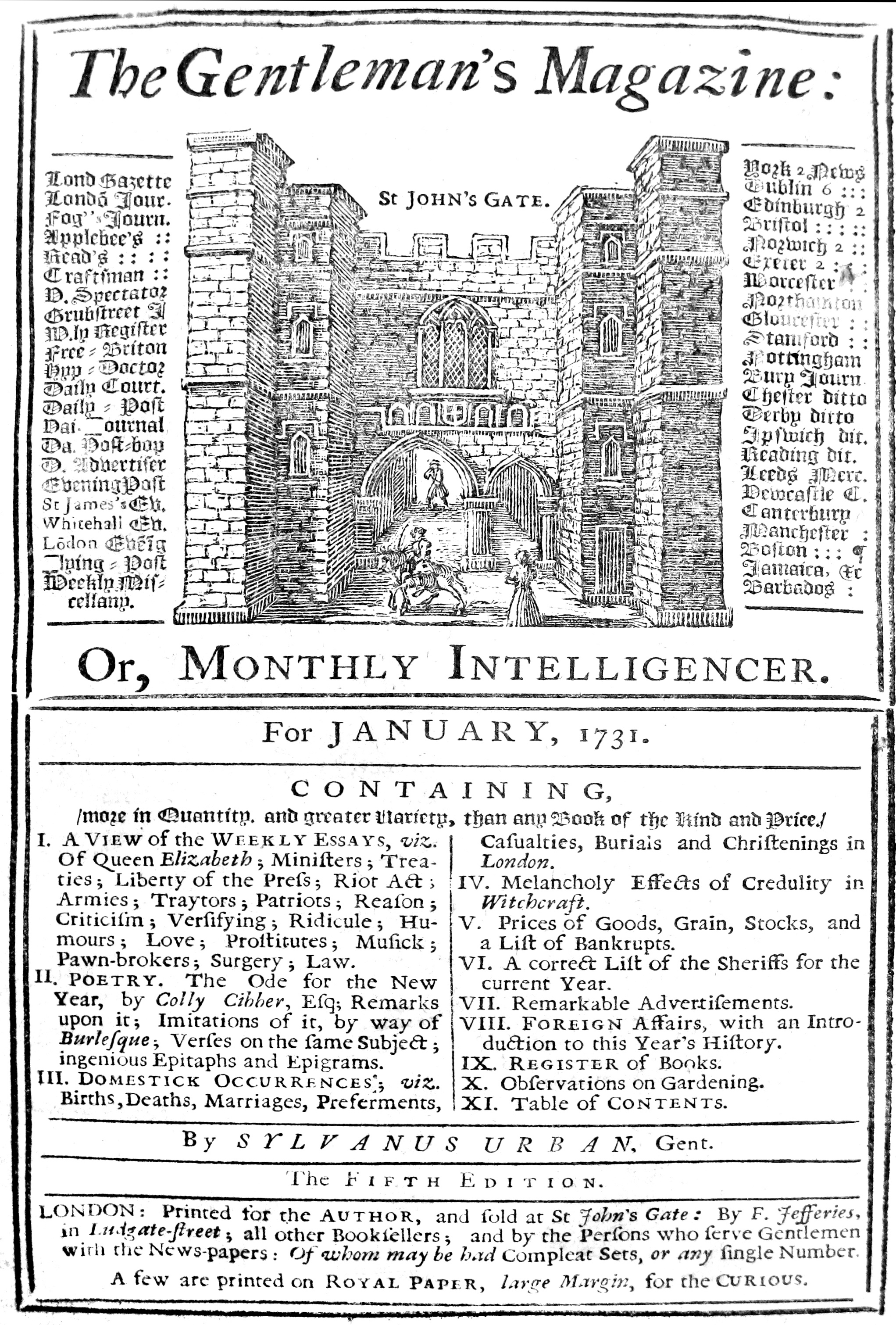

In 1731, this thing called The Gentleman’s Magazine was invented and, with it, the word “magazine”, which originally just meant a container or repository of lots of good things. It was telling that the man who invented The Gentleman’s Magazine, Edmund Cave, was the son of a cobbler, because these new forms of print and publishing allowed new kinds of people (often from quite lowly backgrounds) to make lots of money.

Image of the title page of the first issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine. By Uploader. Magazine published by Edmund Cave. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

That’s the background to what was happening in literature in the 18th century. Literature became something that got bought and sold.

Satire vs. Grub Street

The kinds of literature that came into being in the early 18th century range from works we still study at university to acres of print that are now forgotten or can only be recovered in very large libraries.

Among the things that have “swum down the gutter of time”, as the 18th century novelist Laurence Sterne put it, are the greatest satires of the early 18th century, including works by figures such as Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift. Strangely enough, these were men who themselves deplored the great outpouring of print they saw around them, which to them was a kind of recipe for mediocrity and what Pope called “dullness”. Pope’s greatest satirical poem, The Dunciad, is a mock epic about bad writers on Grub Street, a topographical metaphor for what happens in the 18th century. It’s a real street in London that’s now mostly built over by the Barbican Centre, but it’s a metaphor for the business of hack writing. Ironically, the conditions that produced all this great satire also produced men who deplored those conditions.

Travellers’ tales and true crime

1719 sees the publication of what many people think of as the first proper novel in English, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. By this time, Defoe is in his late 50s and he’s been writing all sorts of things all his life. He’s a kind of hack, and he notices that there’s a great new fashion for voyage literature: tall tales by travellers. He writes his own fictional version of this, which is hugely successful but not regarded as great literature at the time. He follows it up with tales of pirates and criminals: Moll Flanders, Roxana, Captain Singleton.

Looking back, we think: there’s the invention of the European novel. Yet, people didn’t think that at the time. Rather, they saw an elaboration of these rather low and vulgar forms of fiction or publication, which were mushrooming in the early 18th century, with a particular focus on crime. Then, frankly as now, stories of crime, real or imagined, were hugely popular and were being churned out.

Making fiction respectable

Contemporaries might not have noticed Defoe’s fiction, but they certainly noticed Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, published in 1740. This novel, which was a huge bestseller and goes through many different editions, was really the beginning of the rise of the novel. One of the reasons is not just because it sold lots of copies – which is certainly important because the novel is a brazenly commercial genre which exists to be sold – but also because it’s morally earnest. It makes fiction respectable.

Pamela is a first-person account written in letters and diary entries by the heroine, Pamela, a 15-year-old servant girl. It’s subtitled Virtue Rewarded because it’s the account of a servant girl fighting off the often quite sophisticated and always entirely unscrupulous sexual advances of her master. And she triumphs. Essentially, it’s a sort of “Me Too” story.

Mr B. Finds Pamela Writing, 1743–1744. By Joseph Highmore (1692–1780). Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain

One of the subtleties of the story is that the master is busily intercepting Pamela’s letters, and so, in effect, he reads the same novel that we are reading. It converts him. It converts him to virtue. He proposes marriage to her, and she becomes a lady. Even though some of Richardson’s rivals were scornful of this tale, it’s a huge success and nobody can ignore it. From Pamela onwards, the novel exists.

The common reader

Invented in the course of the 18th century is what you might call “the public”: what Samuel Johnson called “the common reader”. In other words, readers as unidentified people who might be anybody; people who, by the later 18th century, if you were a novelist, might get your book very cheaply from a circulating library, even if they couldn’t afford to buy it.

Readerships aren’t just groups of people that historians and sociologists can identify. They’re imagined people in the minds of writers. Just after she publishes her first novel, Evelina, in 1778, Fanny Burney writes in her journal of how tender she feels about the fact that her book, which had previously only been seen by people she knows very well, will now be read by the butcher, the baker and any old person. For her, there’s something rather shocking about that, even in the latter part of the 18th century.

The first literary celebrity

It’s remarkable now to think that a book like Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne was a bestseller. These days it’s regarded as a challenging work, which plays all sorts of tricks with narrative expectations. You study it at university in the same way you might study, say, James Joyce. But in the 1760s it was a bestseller, and Sterne became in some ways the first modern literary celebrity on the back of it.

That story is in itself an indication of how times had changed. Until perhaps the mid-18th century, the proper stance for a successful writer was to pretend that he (or perhaps she, because it’s also a period that sees the rise of the woman writer) actually didn’t want any kind of publicity or celebrity. But, with the success of Tristram Shandy, Laurence Sterne, a middle-aged clergyman from Yorkshire, comes down and lives it up in London. He’s invited to a different dinner party every day and parades himself at the Pleasure Gardens at Vauxhall. He’s a best-selling novelist, a literary celebrity – and lapping it up. That’s a kind of modern character, in a way, and he’s the first novelist to become that modern character.

Discover more about

18th century literature

Mullan, J. (2006). How Novels Work. Oxford University Press.

Mullan, J. (1990). Sentiment and Sociability: The Language of Feeling in the Eighteenth Century. Oxford University Press.

Mullan, J., & Reid, C. (Eds.). (2000). Eighteenth-Century Popular Culture: A Selection. Oxford University Press.