Gandhi’s story has made him the icon not just of non-violence but also of the American civil rights movement and the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. But, above all, Gandhi has stood for non-violence and the story of India’s independence from the British Empire.

Global India, democracy and violence

Historian of Modern India and Global Political Thought

- The thinking of India’s most important 20th century leaders, such as Mahatma Gandhi, was animated by their attitudes towards violence.

- It’s too simplistic to say that Gandhi believed in non-violence. Inspired by The Bhagavad Gita, his more nuanced position was that it was vital to end the State’s monopoly on violence.

- Around the world, politics is becoming more intimate and visceral. This may reflect the influence of India on other mass democracies.

The icon of non-violence

The story of India and its independence movement is a dramatic one. It has been associated with one figure above all: Mahatma Gandhi, the apostle of non-violence. His rise is particularly interesting and important in the 20th century because he is a contemporary of Hitler, Stalin and Churchill – three militaristic, macho figures who sought to transform the globe through military prowess and the use of State capacity.

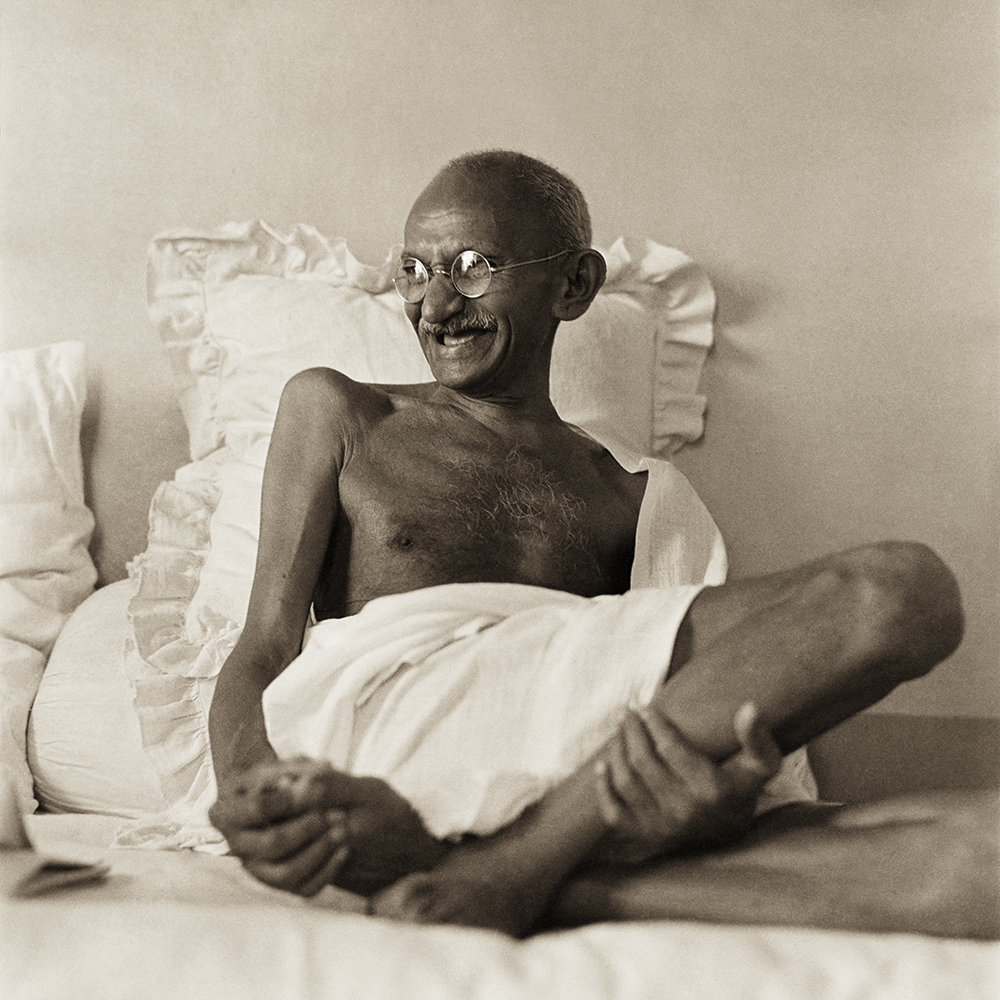

Gandhi smiling, August 1942. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Violence and the birth of modern politics

Non-violence is, in some ways, a negative category. It means the absence or the negation of violence.

The attitude of India’s most significant political actors towards violence animated and remade modern India in very consequential terms. Violence is a central political question. We know this from the age of the civil wars in England and the work of Hobbes. The struggle of modernity is known to be a struggle of capturing violence within the State. Through this process, the State becomes the author and the destination of modern politics. The State also establishes a monopoly on violence. This is how modern politics was birthed. Much of the work of political theorists and philosophers has been to look at this very complicated story and ask how we got here.

A monopoly on violence

The story of India’s independence movement shows some important departures from Western ways of thinking. This was not nativism but rather some tough, reflexive, capacious thinking. The anticolonial nationalists realised that the British Empire could be permanent because, by the turn of the 20th century, it had converted itself into a State which had absorbed all of the violent capacities of Indians. Indians had been depoliticised, and the Empire itself had morphed into a kind of non-violent, welfarist institution.

How could they break this monopoly? I think the big moment of 1905 needs to be seen as a global conjuncture, which is to say that very many similar events were happening simultaneously in the world. It was India’s first mass moment of politics: the Swadeshi, or home rule, movement. It’s when the anti-Statist political subject was born.

An audacious project

The beauty and audacity of this project was that it decoupled the question of violence from the State and wrested it back to the individual. This has profound implications. Gandhi was innovating in this tradition of thinking, as reflected in his monumental commentary on The Bhagavad Gita.

Krishna teaching Arjuna, from Bhagavata Gita. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The Gita became the urtext of modern internationalism and also modern Indian politics more generally. It’s a stand-alone poem in the middle of one of the great epics from the Indian subcontinent, the Mahabharata. The Mahabharata is the epic story of fratricide and the struggles between two groups of cousins. The Gita is really a sermon given at the start of this epic war, when the protagonist, a warrior, decides that he doesn’t wish to fight. He doesn’t want to kill his teachers, brothers, uncles or any of his intimates. In this sermon, Lord Krishna urges Arjuna, the protagonist, to do his duty as a warrior. As a matter of duty, he would have to kill his own.

The capacity of death

The Gita and the Mahabharata become the instigating point or the site on which various Indian political actors, Gandhi included, start rediscovering the meaning of politics in relation to ethics. In this search, they decouple the question of violence from the State and deposit it into the individual. It is not a matter of the State versus the individual, as anarchists would have had it, but rather that, as an individual subject, I have many capacities.

One of the main capacities I have is the capacity of death. This way of thinking is contrary to the liberal tradition, which had always been about protecting and enhancing life. The Gita turns this on its head. Most significantly, this critique of liberalism discovers enmity in entirely intimate and familiar terms.

The enemy within

In recent European history, the enemy has generally been the “other”: the immigrant, the foreigner and, most catastrophically, the Jew.

In India, this is dramatically overturned. The enemy is always in your midst. It’s your brother. This is a profound realisation because, from around 1910 onwards, the British are becoming existentially unimportant to the Indians. Indians can already imagine a politics where the British don’t exist. So, the British are denied even a position of enmity.

Lord Mountbatten swears in Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru as the first Prime Minister of free India at the ceremony held at 8.30 a.m. on August 15, 1947. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

This becomes clearer in 1947, the moment of decolonisation in the subcontinent, when India is partitioned into the two nations of India and Pakistan. The latter is the world’s first avowedly Muslim nation state; the former is multicultural. However, what was significant about that moment was that the British were singularly spared during a period of violence in which, conservatively, a million people died. Moreover, this violence was conducted without the apparatus of the State.

Global India

I don’t know why India is called a subcontinent. It feels like Europe plus plus. When India’s politicians were thinking about decolonisation, they weren’t just thinking about producing freedom. They also had to produce a political form that was going to work in such a massive society. That required some innovation in political thinking.

India should not be seen only as a place or a historical context. It should also be seen as a category in the same way that Europe is a category. It represents the birth of new political norms that are capable of universal projection.

Applying this to the present day, whether in Europe, America or India, our intimates and our neighbours incite our greatest difficulties – to use a less passionate word than “hatreds”. Our politics have become intimate; they have become visceral.

India shows us how politics will unfold in the era of 21st century mass democracies. By “global India”, we mean that India is a habitus of new political ideas which developed in the last century. These political ideas refer to fundamental questions of self-sovereignty, violence and democracy.

Discover more about

global India, democracy and violence

Kapila, S. (2021). Violent Fraternity: Indian Political Thought in the Global Age. Princeton University Press.

Kapila, S., & Devji, F. (Eds.). (2013). Political Thought in Action: The Bhagavad Gita and Modern India. Cambridge University Press.

Kapila, S. (Ed.). (2010). An Intellectual History for India. Foundation Books.

Kapila, S. (2020). India’s societal violence has no fixed face to protest against . Financial Times.