Freud had little or no contact with psychotic patients; however, for Lacan, this was actually the beginning of his clinical training, and it is in that context that he started to become interested in psychoanalysis. In 1923, he had the good fortune to work at a hospital that was run at the time by a surgeon, Henri Claude, who himself was interested in psychoanalytic ideas. So, apart from gaining the standard psychiatric toolkit, Lacan was also imbued with the psychoanalytic ideas of his mentor at the time. That gradually resulted in Lacan, apart from being a psychiatrist, also developing and training as a psychoanalyst.

How Lacan radically changed psychoanalysis

Psychoanalyst and Professor of Psychoanalytic Psychology

- Jacques Lacan radically changed psychoanalysis on the basis of two observations: a person uses language to express suffering; this statement of suffering leads to philosophical questions on how to live a life without suffering.

- Lacan returned to early Freudian concepts, such as the unconscious and transference, but radically re-read Freud with the tools of linguistics and philosophy.

- According to Lacan, we are not in control of ourselves because we are born in a world of language, and our unconscious is structured by language.

Language and philosophical questions

Whenever someone goes to see a psychoanalyst – and in a sense, this applies to any kind of psychotherapist – they have recourse to speech in order to express their suffering. In other words, they use language in order to convey to a clinician what the problem is. In a psychoanalytic context, this initial statement of suffering rapidly develops into philosophical questions about what someone can hope for, how they can be happy, how they can live a life without suffering.

During the 1950s, on the basis of these two simple observations, Jacques Lacan radically changed the psychoanalytic landscape. It is via his rereading of Freud that he managed to give a new dimension to psychoanalysis, and it is via his observation of these two simple facts that psychoanalysis was never the same again.

A radical perspective on Freud

Lacan was very eager to claim that what he was doing was simply returning to Freud. For him, that meant actually returning to the letter of Freud’s works. He was firmly convinced that over the past 20 or 30 years, ever since Freud’s death in 1939, scientific theory and practice had diverged into an educational and ideological doctrinal body of thought. So he claimed that he should and would return to Freud in order to recover the original spirit of discovery.

However, as the years progressed, he brought in his own ideas. He drew on linguistics. He drew on philosophical systems. So what was originally presented as a return to Freud actually rapidly became an entirely new and quite radical perspective on Freudian theory and practice.

Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst

Unlike Freud, Jacques Lacan trained as a clinical psychiatrist. After he completed his medical degree, during the 1920s, he conducted various so-called clinical placements in a number of clinics around Paris. In those clinics, he was confronted with the reality of suffering – a type of suffering that was primarily presented to him by institutionalised psychotic patients.

The entrance of The Saint Ann Hospital in Paris, where Lacan debuted his internship in 1921

Early Freudian concepts

What Lacan takes from Freud are most of the concepts of what you could call the early Freud. There’s hardly anything in Lacanian theory that builds upon the Freudian distinction between the ego, the id and the superego, if only because it was primarily that distinction that had become a cornerstone of one of the deviations that Lacan was criticising.

So he takes the notions of the early Freud: the unconscious, the principle of repression, the fact that hysteria presents the psychoanalyst with a question more than anything else – but also concepts such as repetition, transference and interpretation. In short, he takes the whole theoretical and clinical toolkit that Freud developed roughly before his introduction of this distinction between the ego, the id and the superego in 1923.

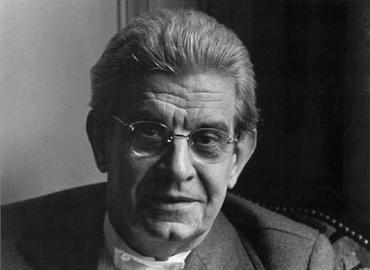

The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. The Australian National University

Refurbishing the Freudian building

Lacan started from this simple observation that people have recourse to speech and language to express their suffering, and that before long, their suffering turns into a series of philosophical questions about their identity, their place in the world. So he felt that he could refurbish the Freudian building with the tools of linguistics on the one hand and with the tools of philosophy on the other.

Primarily in the early Lacan, the Lacan from the 1950s, he is rereading Freud through a linguistic and a philosophical lens. That’s why Lacan is often portrayed as the most philosophical of the 20th century psychoanalysts – but again, this option to draw on philosophy has a clinical rationale. It is there to serve the purpose of advancing the very fact that patients also come with philosophical questions.

Structural linguistics in psychoanalysis

What structural linguistics brings to psychoanalytic practice, according to Lacan, is the fact that the patient’s speech should no longer be considered as a manifest content that is based upon some repressed unconscious meaning; instead, the patient’s speech should be considered in relation to other speech elements. That’s why it’s called structural linguistics. The structure lies in the very observation that meaning is derived from the relation between elements of speech, which is actually quite different from how Freud would have probably seen it.

When Freud starts working with his new psychoanalytic paradigm, it is the classic model of dream interpretation that permeates each and every aspect of his work. It essentially relies on the idea that underneath the patient’s speech, something else is at work. So Freud is more interested in the vertical relation between consciousness and the unconscious, between the repressed and what appears in the conscious mind. Lacan is more interested in the horizontal relation between speech elements, because it is these structural, contextual aspects that have the most important influence on the way in which meanings are generated.

Drawing on Hegel

When Lacan was looking for a philosophical body of ideas in order to renew Freud’s thought, he drew primarily, although not exclusively, on Alexandre Kojève’s interpretation of Hegel’s The Phenomenology of Spirit. To set that in context, during the 1930s, Kojève was a Russian philosopher who’d emigrated to France and who, over a period of no less than seven years, read paragraph by paragraph, line by line, Hegel’s foundational 1807 volume.

What Lacan took from assiduously attending Alexandre Kojève’s lectures on Hegel throughout the seven years was this notion of desire, which features prominently in Hegel’s work, and which for Lacan became a translation, a reinterpretation of what Freud would have called the unconscious wish. However, for Lacan, this notion of desire also extended into at least three different innovative conceptions of the human mind.

Title page of the "Phenomenology of Mind" by Hegel, 1807, Bamberg / Würzburg. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Desire and the human mind

First of all, and this is Hegelian more than anything else, Lacan would argue that desire is not an autonomous force. It is not something that the subject controls. It is almost exactly the opposite; it is as if the subject is controlled or subsumed under desire.

Secondly – and this is already in The Phenomenology of Spirit – desire is never something that operates in isolation from other desires. Desire is always embedded in a conflictual situation, in a struggle with another desire. The object of that struggle is nothing concrete; it is essentially recognition.

So we have the idea that the subject doesn’t own desire, that desire transcends the subject’s conscious control. Secondly, we have the idea that desire is embedded in a conflict with other desires over something that is quite abstract; call it recognition. To these ideas, Lacan added that insofar as desire is directed towards an object, this very object of desire doesn’t really satisfy desire; it always falls short of what desire is looking for. As a result, desire shifts. It moves to something else.

A world of language

If we have to retain one idea from Lacan’s entire theory, it’s that a human being is never in control of him or herself, because human beings are born in a world of language. They, of course, have an unconscious – that’s already in Freud – but this unconscious itself is structured by, conditioned by, predicated upon language. So it’s effectively language, our symbolic environment, that is responsible for the fact that we as human beings have an unconscious and are not in control of ourselves.

Discover more about

Lacan, the thinker

Nobus, D. (2017). The Law of Desire: On Lacan’s ‘Kant with Sade’. Palgrave Macmillan.

Nobus, D. (Ed). (1995). Key Concepts of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. Routledge.