What we call democracy is a recent phenomenon

The idea of democracy is thousands of years old, and most people have a sense of that. Because they believe that it’s the oldest idea, they believe it must be the basis of our own politics. But the notion that what we call democracy goes back thousands of years is wrong. The thing that we call democracy is a much more recent phenomenon. It’s been around for a hundred years or less.

Representative Democracy

When we talk about democracy, we mean mass elections in which everybody has a vote. There are multiple political parties, and we usually think of modern welfare states. We think of mass communication and include mass literacy in that so people can read and understand. None of these things were true in the ancient world. In Athens, two and a half thousand years ago, it was a very different kind of politics. So, when we worry about the end of democracy, we must remember that it’s not that old. Many people alive today have lived longer than democracy.

Another important issue is that what we call democracy is, in fact, “representative democracy”, characterised by an electoral political party system. The name would imply that the core idea is democracy which is qualified by representation; this means we have a representative version of democracy in which we elect people in parliaments, in governments, to make decisions for us.

But I think this is a wrong interpretation. The core idea is not democracy: the core idea is representation. What makes politics since the 18th century different from everything that came before is its fundamental representative structure. We live in political systems where a group of people that we call politicians do this full time. Since the 19th century, at the heart of our politics, a few people have taken decisions for everyone else: politicians, governments, elected officials, parliaments, legislatures. It’s a special group, our representatives, who do politics while we are on the fringes. Politics is a small part of our lives.

Representative politics doesn’t have to be democratic. The Chinese political system today is a representative political system. It has a government, it has politicians and they take the decisions.

The difference with systems of democratic representation is that the core representative element is qualified by democracy with elections and political parties and the ability to get rid of politicians we don’t like onto that core system.

Robust or fragile democracies

There are two things that we tend to misunderstand about democracy. We think it’s older and more foundational than it is. And that could sound frightening and make democracy sound as though it’s a rather fragile and contingent thing that hasn’t been around for that long, as if it’s an add-on to our politics. But I think there’s also a kind of liberation aspect to this, which is my anxiety at the moment, because we focus on the last 5 years, 10 years, 15 years, and we think democracy – this thing that we’ve grown up with – is at risk from Trump or Brexit or Bolsonaro or Erdogan or China or whatever and so we need to hang onto democracy, this ancient idea that is the core of our politics.

But, in fact, we only decide to hang onto the thing that we think of as democracy. And the danger is that we hang onto the thing that we know because we think it’s the only way you can do democracy, the only way you can do politics without it collapsing into fascism or authoritarianism. But there are lots of different ways of doing democracy and lots of different ways of doing representation. And the kind that we’re familiar with from the last 50 or so years is just one version of it.

Ancient vs. modern democracy

Some of our ideas of democracy go back to Athens and the ancient world. We share core principles with that system of politics, including a basic idea of political equality: that all citizens of a state have an equal role to play in the key decisions that shape that state, or rather equal access to an active role in this decision-making. So in our democracy, each citizen has one vote. There is no qualification: you don’t have to pass an exam; you don’t have to own a certain amount of property; you don’t have to be rich. We all get to vote. That idea connects us back to the core principles of ancient democracy.

But in most other respects, ancient democracy was very different. It was much more participatory. We don’t spend our time doing politics, whereas the ancient idea of democracy implied that, as a citizen, politics was your primary role. Your purpose was to take part in politics, whereas today we don’t have to. It’s one of the luxuries of modern life, of representative democracy. We can let other people make decisions for us. We don’t even have to take part in elections.

The privilege of tuning out

The other thing that was true about ancient democracy was that, because being a democratic citizen meant playing this full role in the life of the state, most people were excluded by definition. Women, foreigners, slaves – all were excluded in ancient democracy; while our democracy tries to include as many people as possible. The reason it includes them is because it makes very few demands of them. When we sometimes complain about our politics, we need to remember it is a kind of luxury to be able to live in a world where if you don’t want to do politics, you don’t have to. There is a danger to that, which is everybody stopping and just leaving it up to the politicians, who would not be subject to control. But we do have to remember that our form of politics was devised by people like us, for people like us, so that we could spend most of our lives doing something else. And that’s what makes us modern citizens and different from the citizens of the ancient world. This kind of privilege is easy to forget, but we have to guard it carefully. If we all stop doing politics, we will lose it.

In modern democracy, as we know it, we let professionals do politics for us, but we can complain about them and get rid of them when we don’t like them, having elections to choose different professionals.

We’re starting to see in our politics more movements for direct participation, referendums, street politics, forms of citizens’ assemblies. People are frustrated with professional politics and with letting other people make decisions for them. But letting other people make decisions for us is the central principle of our version of democracy.

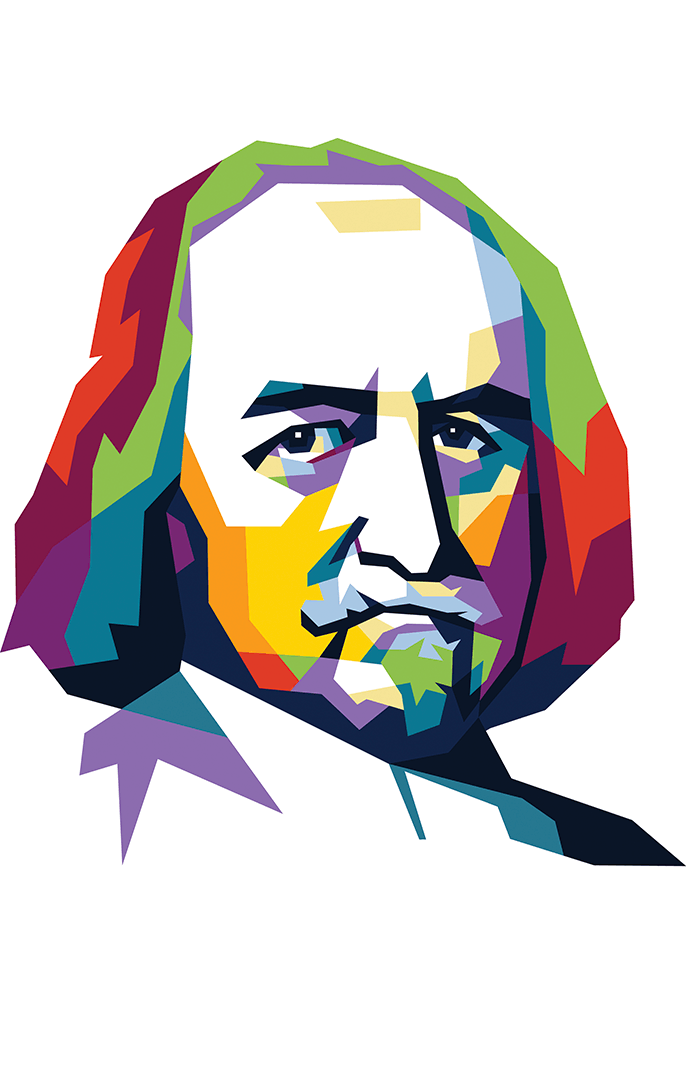

Thomas Hobbes's legacy

Thomas Hobbes is a very important philosopher for thinking about modern politics, but that’s partly because he wasn’t a democrat. Historians argue about this – and bits of his philosophy can have a kind of democratic application – but the basis of his philosophy was that actually it doesn’t matter what kind of political system you have. It could be monarchical, aristocratic, democratic; you could be ruled by one person, a few people or many people. The key thing for Hobbes is that some individual or group makes a decision for the whole.

So Hobbes is the foundational philosopher not of democracy but of representative government. And that was the word that he used in his great book, Leviathan. And he helped to introduce it into modern political language: the sovereign, what we might call the government, is representative of the state.

So we’re all members of the state. We all belong to the state. But the decisions taken on behalf of the state, on behalf of us, are made by a representative, either one person or a group of people. And for Hobbes, we make that arrangement because it’s essential that in every political system there is some single source of authority.

We’ve qualified that many times over the centuries since Hobbes, by introducing democratic principles and institutions to allow us to control or hold accountable representative decision-makers. And it is still the case in democracies like Britain, France or the United States – any country in the world that calls itself a democracy – that once elected or chosen, governments do have a single authority to make decisions, particularly in a crisis.

At the time of COVID and the coronavirus crisis, we’ve become acutely aware of this. It’s easy to forget it, but in a real political crisis, particularly when people’s lives are on the line, we don’t decide our fate. Citizens don’t decide what happens to them. We don’t decide what happens on a day-to-day basis. And in a crisis, that power is relatively unaccountable. Our representatives decide and make life and death decisions for us.

Hobbes reminds us that in politics, the decisions are life and death. People die because of what governments decide, not because the governments kill them. Every fundamental political decision can be a matter of life and death. And the COVID crisis has shown that to us: what our governments decide for us will mean for some people whether they live or die.

In that respect, even though ours is a much more democratic world than the one that Hobbes imagined, it’s still Hobbes’s world.