There were two aims here. Firstly, they urgently needed to get the infrastructure going again, and that included universities, libraries, newspapers and magazines. The Germans needed to be educated and informed, and they needed writers to help with some of this. Secondly, the occupiers explicitly wanted to turn the Germans into democratic and peace-loving people, and they thought that books and films from successfully democratic nations could help them do that, which was obviously an extremely controversial thing to do, given that the Germans had had a high culture of their own for years. Nonetheless, that was what they hoped to do. So, suddenly, a generation of British and American writers and filmmakers found themselves the vanguard of the campaign to remake a country.

Denazification and culture in post-war Germany

Professor of Modern Literature and Culture

- The occupiers of Germany after World War Two – Great Britain, the US, the Soviet Union and France – all took responsibility for reconstructing the country economically and politically.

- German-speaking foreigners hoped they could provide a useful service connecting the German cultural figures who’d resisted the Nazis with the occupiers, to get German culture going again rather than just importing culture from abroad.

- The Germans responded ambivalently to the imported cultural offerings, though they were delighted that the cinemas and the theatres were reopening.

Germany under reconstruction

I became interested in what happened to culture in post-war Germany because it seemed a way to think about how culture responds to or fails to respond to political upheaval and social disaster. In May 1945, when Germany surrendered, Britain, America, the Soviet Union and France divided the country into four zones, and each sent in a force of occupation to administer their area. The occupiers all took responsibility for reconstructing the country economically and politically, which we all know. What’s less well known is that they also took responsibility for cultural reconstruction. Each occupier sent in writers, filmmakers and artists to help rebuild the cultural sectors in the country that their armed forces had just spent five years destroying.

The Brandenburg Gate photographed in May 1946. The presence of the Allied occupation troops is evident. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The artists themselves

In my book The Bitter Taste of Victory, I look at 20 cultural figures who found themselves in Germany in British or American army uniform. Among them was Stephen Spender, who was sent back to be in charge of denazifying libraries and universities, and W.H. Auden, his great friend, who was charged with reporting on morale in the bombed cities. Both Spender and Auden had spent time in Germany in the 1920s and regarded German culture as far superior to British culture. As German speakers, they both hoped they could provide a useful service connecting the German cultural figures who’d resisted the Nazis with the occupiers, to get German culture going again rather than just importing culture from abroad. Some of the figures sent into Germany were Germans and Austrians who’d emigrated during the war and went back in the guise of conquerors, which often provoked resentment amongst their former compatriots. Among them were the writers Klaus and Erika Mann, children of Thomas Mann.

Marlene Dietrich from the trailer for the Alfred Hitchcock film Stage Fright. 1950.

There was also the great actor and singer Marlene Dietrich, who’d spent the war entertaining American troops. Billy Wilder, the Austrian filmmaker, was sent to be in charge of reconstructing the film industry in the American zone where they had lived in Berlin before the war. Wilder had spent the war in America, worrying about where his mother and grandmother could be. He believed they must have been taken to concentration camps. He wanted to make the first documentary about the camps and, in the process, hoped to find out more about his relatives. He began his time in Germany by watching hour after hour of appalling footage from the liberated camp, scouring the screen in the hope of finding his relatives.

At the same time, Wilder fulfilled his task, which was to attempt to revive the film industry in the American zone. He had to go to the studios and see what equipment could be saved, but gradually he became disillusioned by the bureaucracy of the occupation forces and found that it was basically impossible to get through the red tape and make a film. However, his zest for life took over and he became intrigued and excited by life in post-war Berlin. So, amid all the horror, he made the surprising decision to write a comedy, set in the Berlin ruins, and he decided to make it for Hollywood rather than for the occupation forces.

Success in their goals?

Spender was certainly successful in denazifying the libraries and the universities, and he did bring sort of large libraries from Britain. There was a book list of appropriate writing, which was broadly seen to be democratic. I argue in my book that Germany had a greater effect on these people than they had on Germany. I don’t think in the end that Spender and Auden managed to revive the more interesting elements of German intellectual life. At the same time, Spender did write what was, for me, his masterpiece, a book called European Witness, where he describes the ruins of Europe and attempts to decode what they mean.

Although Billy Wilder failed to get the German film studios back into action, the comedy he set in the Berlin ruins, The Foreign Affair, is, I think, one of his two or three best films. It’s given its lustre by the performance of Marlene Dietrich, who, at first, said no when Wilder asked her to come along and play a woman who’d had affairs with senior Nazis. He somehow managed to persuade her to do so, and she did it, giving this astonishing performance. The conceit of the film is that she has had affairs with senior Nazis, but now she pragmatically decides to go for an American GI.

Wilder really brings out the ambivalence of the situation. At this point, he’s not straightforwardly condemning the people who’ve gone along with the Nazis and are now going along with the occupiers. There’s a really great speech where the GI accuses Marlene Dietrich of exploiting him and she says that she’s lost everything. She’s lost her possessions, her beliefs and her country. She’s endured night after night of sitting in air raid shelters and then the arrival of the Red Army, and she can’t see how he can come here in American uniform and tell her that she’s been wrong to try and keep going.

An ambivalent German response

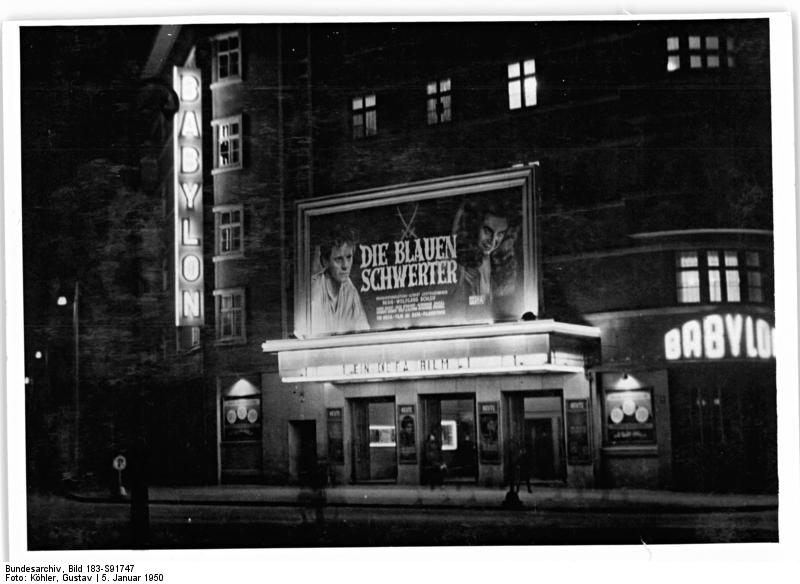

The Babylon-Filmtheater in Berlin. 1950.

The Germans responded, unsurprisingly, very ambivalently to these cultural offerings. They were delighted that the cinemas and the theatres were reopening. There was an astonishing appetite for sitting in freezing theatres and watching the offerings given them by the occupiers. When opera started again, huge audiences turned up. However, they were particularly resentful of the Germans who’d left, like the Mann children, and who then came in and told them that they’d done everything wrong, that they were here to save them from themselves.

There were sarcastic reports in the German periodicals which, of course, were censored by the British and American occupiers. It was a very complex balancing game. I think there was resentment amongst the Germans as well as gratitude; they were aware that their own occupations hadn’t been so generous-minded, hadn’t been reviving culture in the places they’d occupied, and they were grateful to be going back to the theatres again.

Reconstruction: a missed opportunity?

We can see it is a missed opportunity in lots of different ways. Spender and Auden were right to hope that the best elements of German culture could be rescued and rechannelled, rather than just flooding Germany with American culture. This proved tricky immediately after the war. I think their hopes for a reflective, self-critical culture were interrupted swiftly by the Cold War, which I see as beginning on the ground in Berlin in 1947. Suddenly, at that point, it all became about showing off and competing with the Russians: when the Russians brought a huge choir to Berlin and staged spectacles of music, theatre and film, the British and Americans had to do the same.

Often, in the process, they abandoned denazification. At the same time, many of the writers and artists whom Spender and Auden were championing were now dismissed as communists and couldn’t perform. You get a sense that the real heroes of this period were of people like Furtwängler, who should probably have been more strongly denazified. As things moved on, I think even larger opportunities were missed for culture to matter at all in the post-war period. Part of what I like about this moment is that it felt like a moment when culture was at the heart of politics and cultural figures had the power to direct the world for the better. For example, when UNESCO was founded in November 1945 to prevent war, it guided itself with the credo that: “Since wars begin in the minds of men, it’s in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed.”

This was broadly accepted at the time in a way that is hard to conceive of today. At the same time, many of the artists who were sidelined had been fighting for a vision of a united Europe and believed that a shared cultural heritage and a shared desire for peace could transcend national loyalties. At this moment, when it’s quite hard to articulate a European identity that people can believe in, I look back on the post-war moment and think that if culture had remained central to the European project, we might have done a better job at constructing our identity as Europeans.

What value does culture have?

I think the whole story speaks to a situation now where no one’s quite sure about what the value of culture is. We’re presented with two paradigms in this post-war period. There’s the American optimism about what culture is and what it can do; if you just bring in some books and films, you can transform a nation. However, there’s also the pessimism induced by knowing that, despite its great culture, Germany succumbed to Nazism. Perhaps in the face of those, it’s inevitable that no one in the end could find a way forward, but I’m not sure where it leaves us. Should we continue to fund culture because it will rescue us from decay, or should we trust our iconoclastic artists to make their way through the wastelands, whatever history throws at them?

I think the Cold War project in which both America and Russia were investing heavily in culture very much emerged out of this period. A magazine like Encounter, which for a while had Stephen Spender as an editor, really came out of this moment in which they decided that they could influence the hearts and minds of nations through writing. Encounter emerged from a magazine called Demonat, which began in Germany in 1947. It was very much the American thinking that they needed to provide the Germans with a high cultural offering, with brilliant writers writing brilliant things, but with an American message.

I think the attempt to turn Germany into a peaceful and democratic culture through culture was in the end a failure, partly because Germany had a perfectly good culture of its own. Yet, the bombed cities and collapse in morale transformed the work of a handful of writers, filmmakers and artists who encountered them.

Discover more about

the aftermath of World War Two in Germany

Feigel, L. (2016). The Bitter Taste of Victory: In the Ruins of the Reich. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Sollors, W. (2014). The Temptation of Despair: Tales of the 1940s. Harvard University Press.

Brockmann, S. (2009).German Literary Culture at the Zero Hour. Boydell and Brewer.