Once upon a time, people thought torture could produce truth. Some of the people who tortured during the Inquisition or, for example, under the brutal regime of Thomas Cromwell thought they were securing information. But I don't think anybody seriously believes that today. Any of us who have endured even modest pain will do anything and invent anything to cause it to stop. So that seems absurd.

The enduring evil of torture

Professor of Human Rights Law

- There seems to be an increased level of irrationality in modern culture that has eroded the consensus that torture is an unnecessary evil.

- Laws against torture, both international and domestic, make it much harder for future leaders to backtrack on their country’s human rights commitments.

- When we accept torture, whether it’s for reasons of cruelty or some spurious quest for information, we have given up on a value-based society.

The mystery of torture

It’s an enduring mystery: why does torture return? Why can we never seem to shake it off? If civilised societies can agree on nothing else, surely they can agree to end torture? Why does it come back?

There does seem to be some astonishing need for some kind of brutality. For many, it finds its focus in support of this horrible practice.

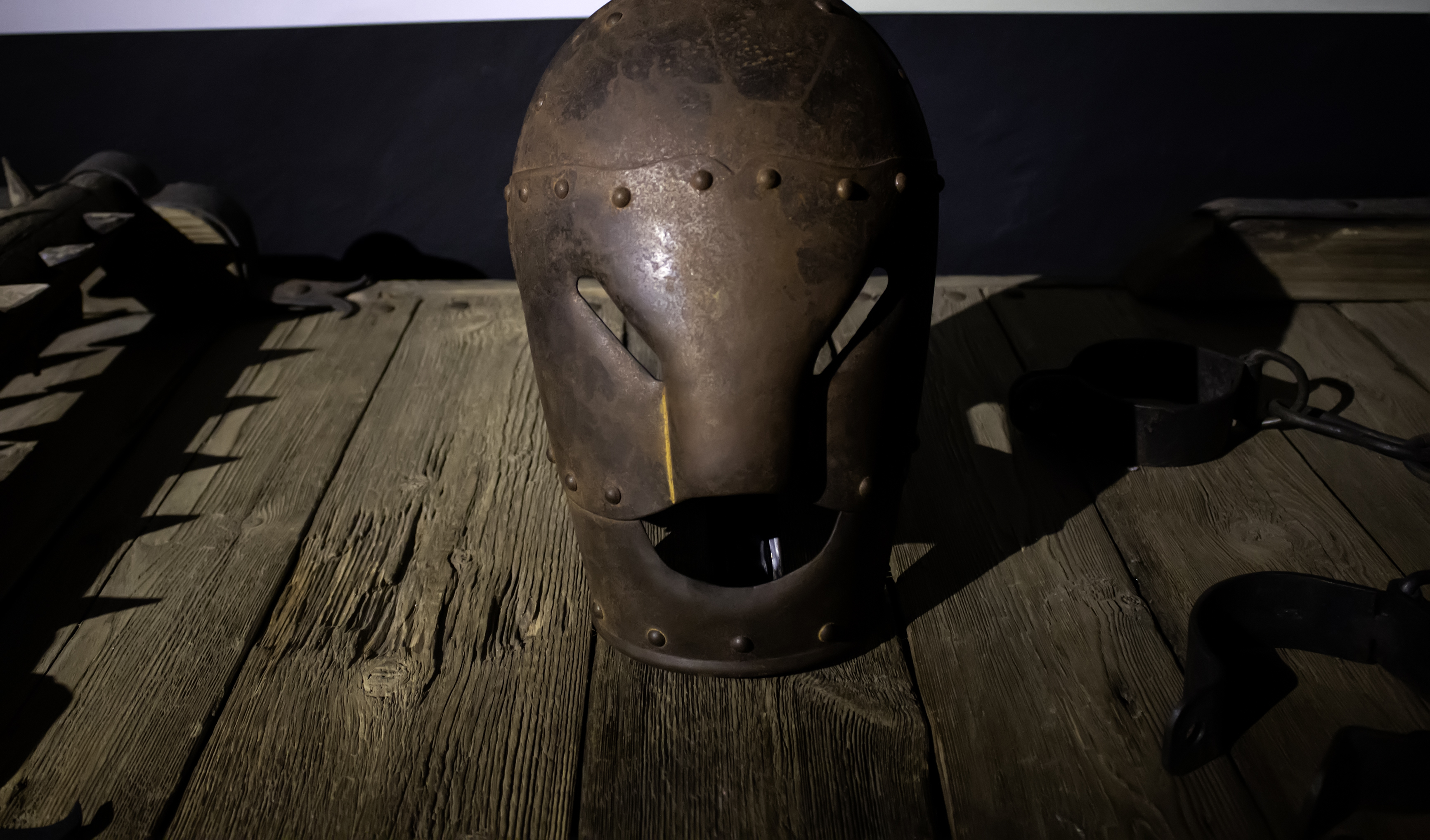

Photo by Celiafoto.

Cruelty or a lack of resources?

There seems to be more irrationality in our culture now than there was when we all agreed “thus far and no further” regarding torture. There appears to be a propensity to cruelty in some people, which leads them to support the deployment of torture against others.

Sometimes, torture may be a consequence of poor resourcing. I did a lecture at Rome’s NATO College, and an English general who was there told me that you could get what you want from people if you've got the time and the resources. However, in recent episodes of torture, it's been poorly paid prison guards who have been responsible. It's been impossible for those in charge of such people to give them the training to secure the kind of confidential relationship with prisoners that produces results.

Torture also meets the needs of a public that is conditioned to applaud cruelty. I'm not sure that army or military leaders are so keen on torture. Its use is driven by this combination of poor resourcing and populist leadership.

The legal war on torture

One of the great achievements of the postwar and Cold War periods was the agreement of an international framework to prevent torture. It was one of the most sophisticated international agreements of the postwar era. Large numbers of countries signed up to it. And it's not only a piece of paper written down and agreed at the United Nations. It's supplemented by committees whose jobs are to oversee the conduct of authorities in countries to ensure that no torture occurs. Many countries also have domestic laws to take action against possible or proven torturers.

Why use law? Law is the guarantor of a set of values that stands outside politics. Law is what countries enact or join to commit themselves to ideals and values. Law is a way to bind future leaders from engaging in practices that we deplore now but cannot be sure we will deplore forever. That's the power of law. It takes a lot of effort to change laws. It will be especially difficult to change international agreements or domestic laws against torture because it would require you to explicitly admit that you are willing to support this practice. That is something few governments are inclined to do.

Colonial methods in Northern Ireland

Sadly, there are many examples around the world of the deployment of torture by state authorities. One that is particularly close to home for me is Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom, became immersed in civil disorder in the late 1960s – so much so that British forces were sent onto the streets there in 1969.

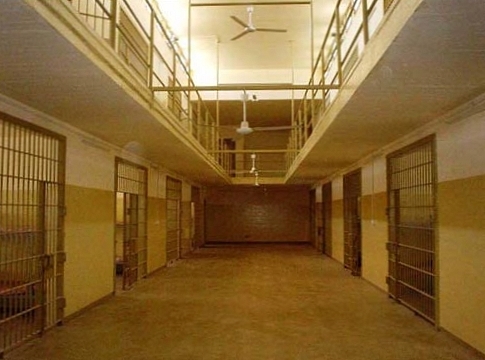

Photo by Evan McCaffrey.

Very quickly, a movement emerged which was determined to achieve unity with the Republic of Ireland. The IRA were its primary emblems and fighters. British forces, fresh from engagement with colonial insurgencies elsewhere, approached the mission in a colonial way. They engaged in detention without trial, military curfews and so on. They detained suspects and submitted them to sensory deprivation to elicit information. This was done from the belief that you can break hardened enemies by subjecting them to sophisticated techniques like sleep and food deprivation, continuous noise and hooding.

This became a cause celebre in the 1970s and a poisonous sore in British relations with the Republic of Ireland and the Catholic community in the North. Newspaper investigations brought to light this ill-treatment, which the British authorities tried to cover up by denying that it was happening. Then they admitted it was happening but denied that it was torture. Instead, it was “robust interrogation”. Eventually, under pressure, UK Prime Minister Edward Heath acknowledged in 1972 that torture had taken place but that it had stopped. He promised that the British state would never engage in such techniques again. A memorandum was sent to all of the relevant authorities, and it was drilled down the ranks that methods such as sensory deprivation were now banned.

The Irish case against the British in the European Court of Human Rights was finalised in 1978. Interestingly and against the advice of an earlier commission report, it was held that it was not torture but rather “inhuman and degrading treatment”. This was a finding that the Irish have always regretted and sought to change a few years ago, unsuccessfully.

21st century torture

After 2001, and in particular, after the 2003 invasion of Iraq, in which the British assisted the Americans, the whole issue of torture returned. And despite the prime ministerial guidance from 1972, it was found through legal cases and action that there had been similar levels of abuse. Some of them were cruder and more brutal, including people being beaten up, killed or subjected to the most horrific treatment.

A Review of ICITAP's Screening Procedures for Contractors Sent to Iraq as Correctional Advisors, February 2005, Exhibit 5b: Photograph of Abu Ghraib Cell Block After Reconstruction, The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) in the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Various army investigations found nothing wrong, or if they did find something wrong, assured everybody it was no longer happening. It took a series of judicial investigations to winkle out the truth. British and American forces were engaged in torture and ill-treatment in Iraq. Not only that, but they were seemingly unaware of the prime minister’s statement from 1972. It had been forgotten. This solemn promise from 1972 had not survived the new conflict. It’s one of those shocking facts that reminds us torture seems never to go away – even when prime ministers have prohibited it.

How to see torture for what it is

Next time someone unconnected with the debates about torture has a passing, appalling pain, let them reflect on the accident of that pain and the importance of its alleviation.

Let them then imagine that their elected representatives have authorised people to inflict this pain on others deliberately.

Let them acknowledge that it’s impossible to get at truth through torture because persons in such pain are shockingly unreliable.

Let them reflect on why torture happens and notice that the people on whom it is inflicted are unlikely to be like them.

Let them try to empathise with the victims of torture by seeing them not as asylum seekers or supposed terrorists but as humans with the same vulnerable body as them.

Finally, let them restate how profoundly unacceptable this is. When we accept that we can instrumentalise the human body, whether it’s for reasons of cruelty or in some spurious quest for information, we have given up on a value-based society.

Discover more about

torture in the modern world

Gearty, C. (2005). 11 September 2001, Counter-terrorism, and the Human Rights Act. Journal of Law and Society, 32(1), 18–33.

Gearty, C. (2007). Terrorism and Human Rights. Government and Opposition, 42(3), 340–362.

Gearty, C. (2020). British Torture, Then and Now: The Role of the Judges. The Modern Law Review, 84(1), 118–154.