It is strange that a philosopher who lived several hundred years ago should be such a source of inspiration for us now, both for ordinary readers and for academics of various kinds, authors and so on. I think part of the reason may lie in Spinoza’s biography, in the fact that he lived both inside and outside Dutch society.

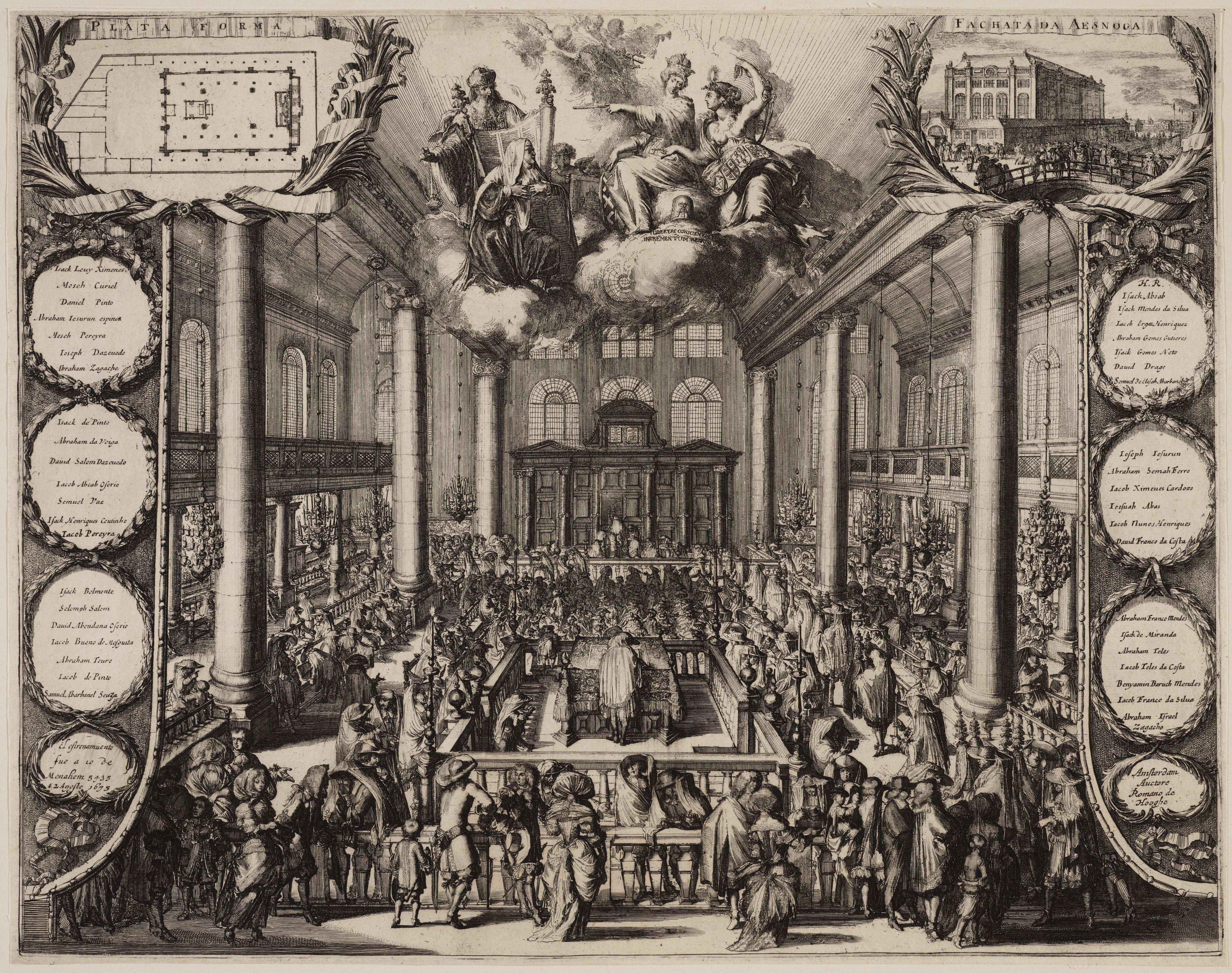

Spinoza was born into a well-established Portuguese Jewish family within the Sephardic Amsterdam community, in which he grew up and was educated. In his early twenties, he entered into a terminal quarrel with the authorities of the synagogue, who eventually excommunicated him. We can tell from the curse, or cherem, that they pronounced over him that they were deeply displeased with him, partly for his financial conduct but also, it seems, for his heterodox views. Spinoza was already beginning to go his own way. When he left the synagogue, as far as we know, he cut ties with the Jewish community – as the cherem required him to do – and set out to remake himself.