What the Enlightenment supposedly did was to banish that idea and to say, by contrast, that human beings come into the world as equal and free. Here, one of the crucial figures was the 17th century English philosopher John Locke, who said that human beings are not born slaves to any master; they’re not born subject to any king; they come into the world free and equal. Moreover, the only way in which other human beings can come to have power over them is if they consent to it.

The Enlightenment and early modern feminism

Senior Lecturer in the History of Ideas

- While the Enlightenment supposedly championed values of freedom and equality, it ignored the situation of slaves and women.

- Early modern feminists saw women as enslaved because their wellbeing depended on their husbands.

- To challenge the status quo, early modern feminists had to prove that women were capable of rational thought, which is why access to education became central to their arguments.

A supposed dawning of light

The Enlightenment was supposed to be this dawning of light over the irrational past in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was supposed to be a banishment of old, irrational, nonsensical, ideological, tyrannical, brutally hierarchic ideas, and a replacement of these with beliefs in freedom and equality.

One crucial idea that the Enlightenment supposedly supplanted is the idea that people are born into subjection. There was an old patriarchal idea that government and kings were appointed by God, and their rule was natural. There was an analogy that was made between the rule of the king and the rule of the father. So political power both came from above – came from God – and was also natural.

Liberation of a black slave by Juliaan Joseph De Vriendt, Julien De Vriendt. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The shadows of the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment absolutely did not live up to its name. It left great swathes of people in the shadows without freedom and without equality. This happened most shockingly and explicitly in relation to slaves. As the abolition medallion pointed out, ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’

There was this idea that the Enlightenment philosophers were talking about the equality of men. And yet, am I not a man, am I not a brother? Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery, posed the crucial question: what to the slave is the Fourth of July? Your values – you American founding fathers of independence, of liberty – mean nothing to a slave.

In addition to chattel slaves, it was also women who were excluded by these Enlightenment values. Mary Astell, a 17th century English feminist, famously asked the very pertinent question: if all men are born free, how is it that all women are born slaves?

The hard reality for early modern women

The situation for early modern women was dire. If one thinks about how they were regarded in English common law, wives were under the system of what’s called “coverture”. That meant that when you married, your legal identity was literally covered by that of your husband. You no longer had an identity of your own. You no longer could possess property of your own. Everything that you had was actually the property of your husband. Even the rings that he gave you were his.

That extended also to your body. A husband might, “within reason” as the law said, beat his wife if she didn’t bend to his will. The whole idea of marital rape was an oxymoron at that time. Indeed, it was in the 17th century that the jurist Matthew Hale talked about how it wasn’t conceivable for a husband to rape his wife because she’d already consented to sex in the marriage contract.

How early feminists saw the enslavement of women

There was that physical slavery, as it were, that physical vulnerability to violence, that being owned by somebody else. But it’s also interesting to reflect on the full nuance and richness of early modern feminist analysis of why, as far as they were concerned, women were slaves. They drew on a theory that historian Quentin Skinner has identified as a neo-Roman theory of liberty. This is an idea that goes back to Ancient Rome.

According to this theory, there are two kinds of legal status. Either you are sui juris, under your own will, in which case you’re free, or you are under the will of somebody else. You’re dependent for your wellbeing on somebody else. It was that relation of dependency, of arbitrary power, that early modern feminists hooked onto and thought precisely described the situation of women in early modernity. And that wasn’t just abhorrent to them because it rendered them slaves, juridically speaking, but because of what it did to their personalities.

If you’re entirely dependent on the will of somebody else for your wellbeing, then various things happen to you. You become obsequious, flattering, unable any more to speak truth to power. You become corrupt as a moral person. You lose all sense of yourself, because your entire sense of self is directed towards trying to please the other.

This recurrent thought was articulated, for example, by Mary Astell, but also by Mary Wollstonecraft, an English feminist of the late 18th century. She made the point, as Astell had, that because of this inequality of power, the entire business of a woman’s life was to please. The entire energy of a woman goes out into a man and leaves the woman hollowed out and lacking in personhood and selfhood.

Proving the rationality of women

One of the main charges that was levelled against women by men, who wanted to justify the fact that women were subordinate to men, was that women lacked reason. They couldn’t think for themselves, and therefore they needed the government of men to guide them. They needed those beings with rationality, that’s to say men, to show them how to live and what to do.

This is a very deep and old idea that goes back to Aristotle. Along with his argument that there are human beings who are naturally rulers and human beings who are naturally slaves, he had a version of this in relation to men and women. According to Aristotle, women’s passions override the little bit of reason that they have, which is why they need the rule of their husbands to direct them.

This idea is recurrent in early modernity. Locke himself thought that it was right, natural, proper and just that husbands should have jurisdiction over their wives because they were “abler and stronger” than women.

Representation of a women's club under the French Revolution. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

So the project for early modern feminists was to prove that they had reason; to prove that their minds were as capable of rationality as those of men; to prove that while their bodies might be different, the soul – the mind, the anima – had no sex.

Feminist arguments against the status quo

What’s interesting about the early modern feminist arguments is that they concede a lot to the patriarchal criticism of them. They often concede that it’s true that lots of women in early modern society don’t seem to possess much reason, that they do seem to be quite soft in the head and weak in their bodies. But what the early modern feminists argue is that this is not a function of nature or necessity. This is just an accident of culture and power. Most importantly, it is the case because women haven’t been given access to education.

Give women access to education, say the early modern feminists, and they will cultivate their minds and demonstrate that they are capable of just as much flourishing as men. This is why education is absolutely central to early modern feminism. The late 18th century American feminist Judith Sargent Murray argued that if you give a woman a telescope, she will be able to see the stars. It’s ridiculous to accuse her of not being able to be good at astrology if you’re not going to educate her in the way of astrology.

How early modern feminism differed from today’s feminism

When you look at the history of feminism over the longue durée and from all around the world, it’s very tempting to think of it as this unbroken movement against patriarchy. There is a sense in which that’s true. But it’s also important to be attentive to the differences.

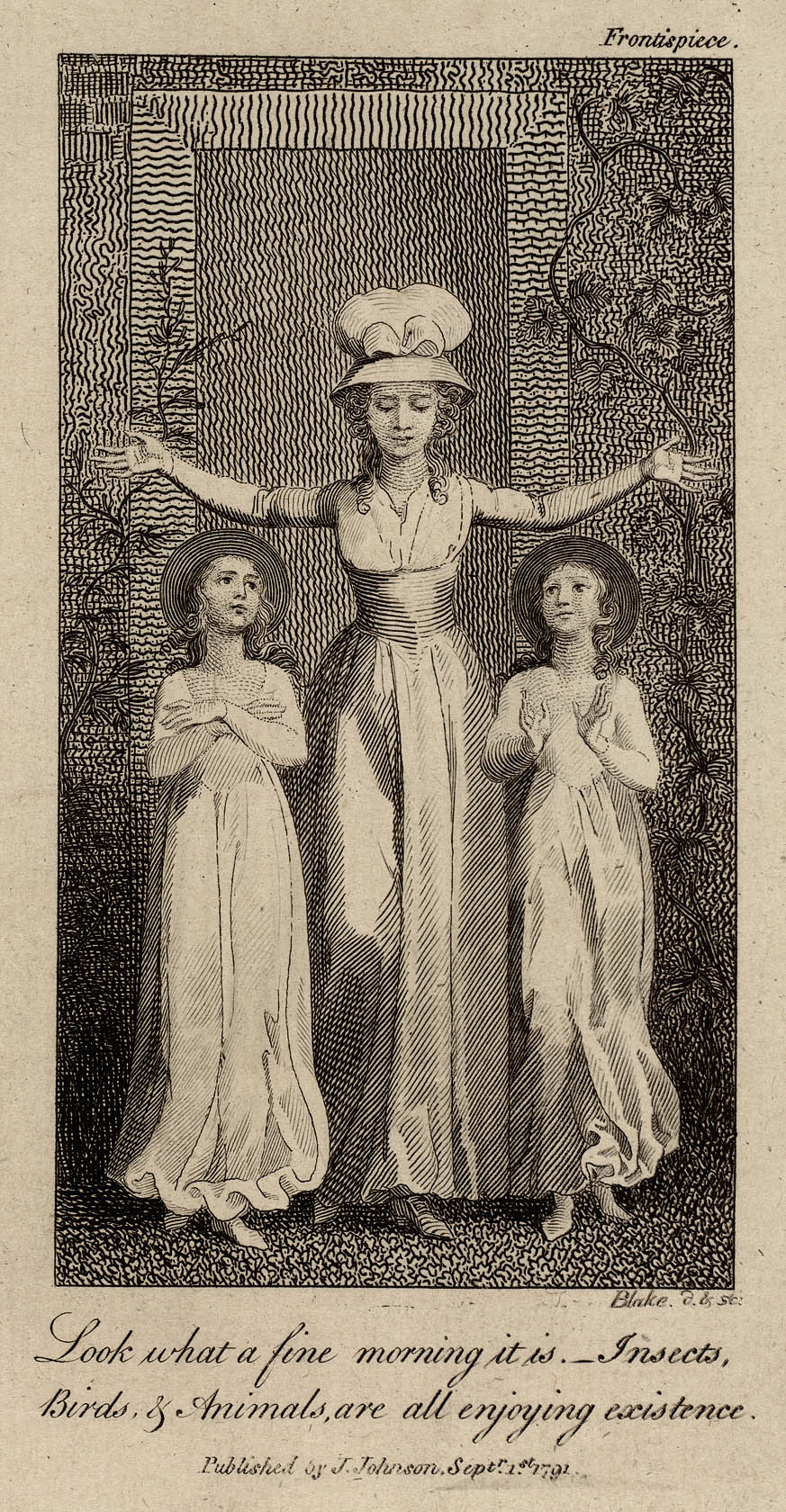

Mary Wollstonecraft Original Stories - Look what a fine morning it is. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

If you think about early modern feminism, they weren’t arguing for the vote. They weren’t arguing for the rights of women in the way that we would think about that now. Mary Wollstonecraft, for example, had a clear idea that there was a law of nature, as she called it, a law like the law of gravity, that would see men and women fall into their separate spheres. Women were, for the most part, to be wives and mothers; that was their natural role. The point was to liberate them within that sphere and allow them the independence and the freedom to cultivate their minds.

What she and other early modern feminists were primarily interested in was not just liberty as an end in itself, but liberty as a means to virtue. Whereas we might think about women’s liberation as the liberation to do whatever you want, that absolutely wasn’t the case for early modern feminists. They had a very clear moral project. Their concern was the way in which patriarchy turned women vicious, turned women cunning, whereas liberty would enable virtue to flourish.

Discover more about

early modern feminism

Dawson, H. (2019). Shame in early modern thought: from sin to sociability. History of European Ideas, 45(3), 377–398.

Dawson, H. (2018). XII—Fighting for My Mind: Feminist Logic at the Edge of Enlightenment. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 118(3), 275–306.