Earliest use of the word

Revolution is one of those terms which is almost impossible to define. It obviously means changing something, but in the ancient world, in Greece and Rome, the term revolution was hardly ever used. Rome moved from the rule of the kings – the mythical seven kings – to a republic, and from a republic to an Empire, and none of these were ever called a revolution. Big events such as the Jacqueries, the peasant revolts in Germany and Britain, were never called revolutions. Major events like the Reformation, whether it’s of Pope Gregory or the Reformation of Luther, were never called revolutions, and even the English Civil War, which some people afterwards called the English Revolution, was really called the English Civil War.

The first time the term is used is with the Glorious Revolution, which actually was not much of a revolution – it was a change in dynasty in Britain, in 1688, going from the rule of the Stuarts to the rule of William and Mary, who was also a Stuart. It’s really with the French Revolution that the term acquires its present connotation of a major upheaval .

‘A big change’

After the French Revolution, the term revolution acquired positive connotations. It was a good thing. Even more recently, things which have really pushed coups d’état, like the colonel’s coup, which led to Gamal Abdel Nasser to be in charge of Egypt in the early 1950s, was called a revolution.

Then, the term, as is often the case in our day, becomes increasingly devalued. Everything that is a big change becomes a revolution. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Boris Johnson talked of the “cycling revolution”, because people were going to use their bicycles more. Before that, the Beatles had a song called Revolution, and the Rolling Stones, too – Street Fighting Man talked about a revolution.

The term included things like the Industrial Revolution, which was a very big change, but it was not one engineered in the sense of a political change. One also talks about the Neolithic Revolution, the beginning of agriculture some 10,000 years ago, which is also not regarded as a political change, but a social one. So, we are in a situation where the term now just means ‘a big change’.

A common trigger

The English Civil War starts as a dispute over taxation between the English parliament and Charles I on who has the right to raise taxes. Charles I refuses and the war begins between the royalists and the parliamentarians in 1642. This war ends up with the execution of the king and the victory of parliament.

In the American case, the issue was, who has the right to tax Americans. ‘No taxation without representation’ is the famous slogan. By 1783, the 13 colonies become independent and they decide they have the right of taxation. The story goes on but, in a sense, it’s about a shift of power.

In the case of the French, it starts again with taxation. King Louis XVI wants to convoke the three estates, the États Généraux, and he’s prepared to give way. To some extent he does, but the thing has been unleashed, so it goes on with the Third Estate demanding more powers, establishing more control over the monarchy, and eventually abolishing the monarchy and executing the king.

In the middle of a war

The three earlier revolutions are all about taxation, and they all end up with a transfer of power. The Russian Revolution and the Chinese Revolution start because there is a war on. Without the First World War, the Bolsheviks, who counted for very little before 1917, would not have had a chance – but there was a war, and everybody was fed up with it. The Tsar is forced to abdicate in March 1917. The cadets, the liberals, take over and a republic is declared.

The tragic mistake of the liberals was to continue the war. The one party that was systematically opposed to the war was the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, who takes over with the storming of the Winter Palace. It’s only the beginning of the revolution. Then, there is a civil war and the Bolsheviks win. That is apparently the end of the Russian Revolution, with the Bolshevik conquest of power.

Finally, we have a Chinese Revolution, which in theory starts in 1911 with the end of a dynasty, but continues with something like 40 years of internecine wars and, above all, the invasion of China by Japan in the 1930s. It is that which contributes massively to the strength and the growth of the Communist Party, led by Mao Zedong, and, eventually, after the end of the Second World War and the expulsion of the Japanese, to the civil war between Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang and Mao Zedong’s communists. That concludes on October 1st 1949, marking the end of the Chinese Revolution.

A shift of power?

It is almost impossible to define a revolution as a shift of power – there are shifts of power all the time. The Conservative Party could lose power and no one would dream of calling it a revolution. It’s not something that we can really know much about.

Even Karl Marx was supposed to have known a great deal about revolutions, but he never really defined what revolution was. It is obviously a radical change, but radical is a word which is also difficult to define. So, one should say a revolution is a revolution when it is generally accepted that it is a revolution. In other words, when the word is such that it does describe the event.

There are many things we cannot easily define: Christianity, socialism, democracy. There is a dispute. We vaguely know what they mean, but we are not quite sure how to propose definitions. In my view, definitions are useless in these cases.

Violence, a fundamental component?

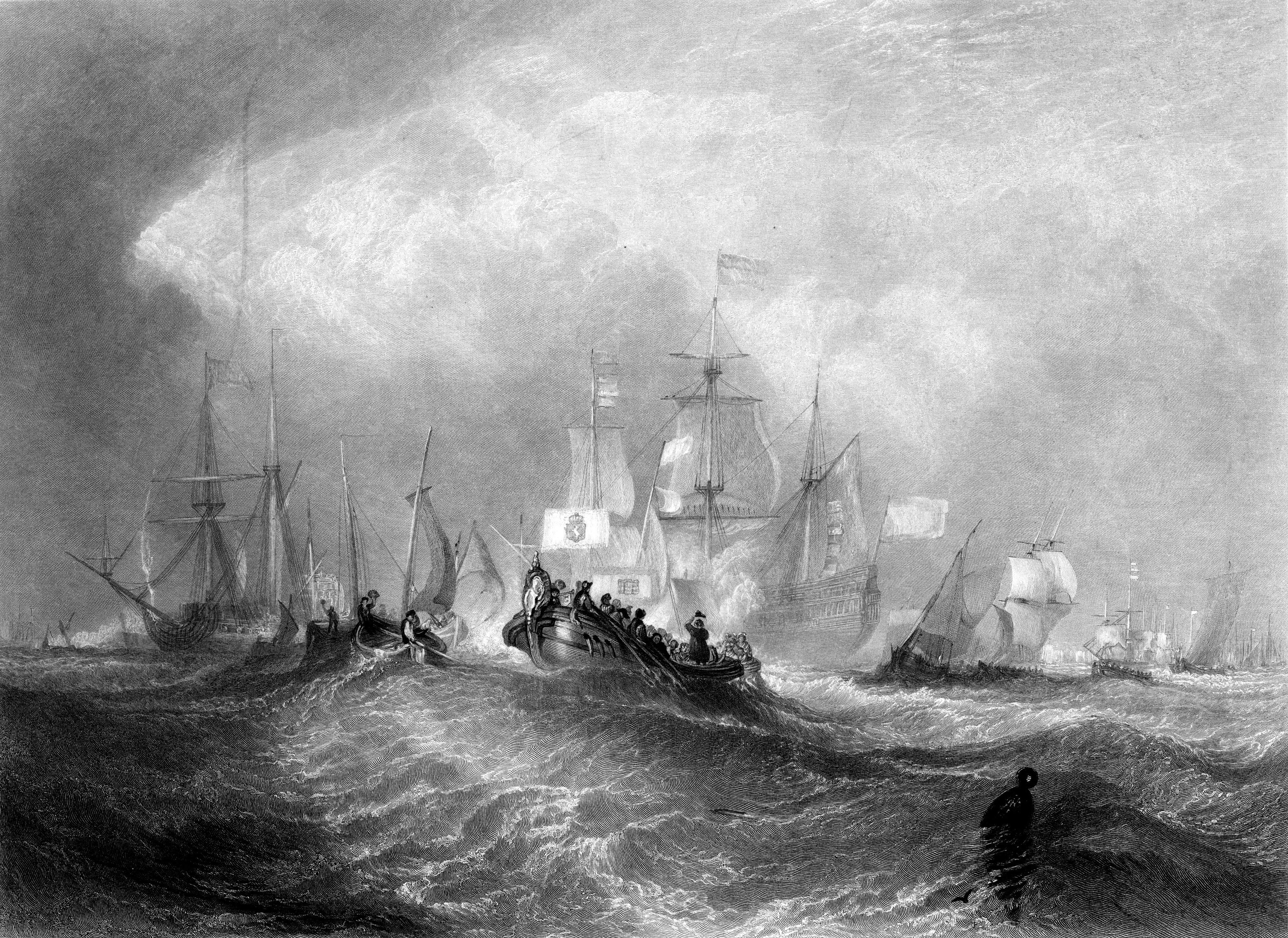

Prince of Orange Landing at Brixham, engraving by William Miller after J M W Turner (Rawlinson 739), published in The Art Journal 1852 (New Series Volume IV). George Virtue, London, 1852. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

In the five examples I have given of events which everybody calls revolutions – the English, the French, the American, the Russian and the Chinese Revolutions – there is no doubt that a lot of violence has been exercised. But if you take the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in Britain, which is one of the first uses of the word, there was hardly any violence. There was simply a change. There was an invasion, but it was more or less a peaceful invasion. So, yes, there is usually plenty of violence, but not necessarily. In many cases, there is plenty of violence and there is no revolution.

Winners and losers

I would say that a revolution is by some people, for some people. If you take the American Revolution, which was the first to have a grand vision, we hold these truths to be said to be self-evident – ‘all men are created equal’ – yet there was slavery, women could not vote, and it was ages before you finally got to the stage where everybody could vote. Even now, as we have seen, many people would think that ‘all men are created equal’ is not something that is accepted by all. So, a revolution starts with a grand vision and grand claims but, in the end, as with everything in history, there are winners and losers.

Revolutions and State building

In the case of the five revolutions mentioned, there is, unquestionably, a State. But if we talk about the unification of Italy, or the unification of Germany, there is no State. If we talk about the anticolonial revolution, there was no State, strictly speaking. Even in America, there were 13 colonies; it was not a State. They wanted to become a State.

So, the revolution is one which not only wants to establish a State, but also some of the elements which would define the politics of the State.

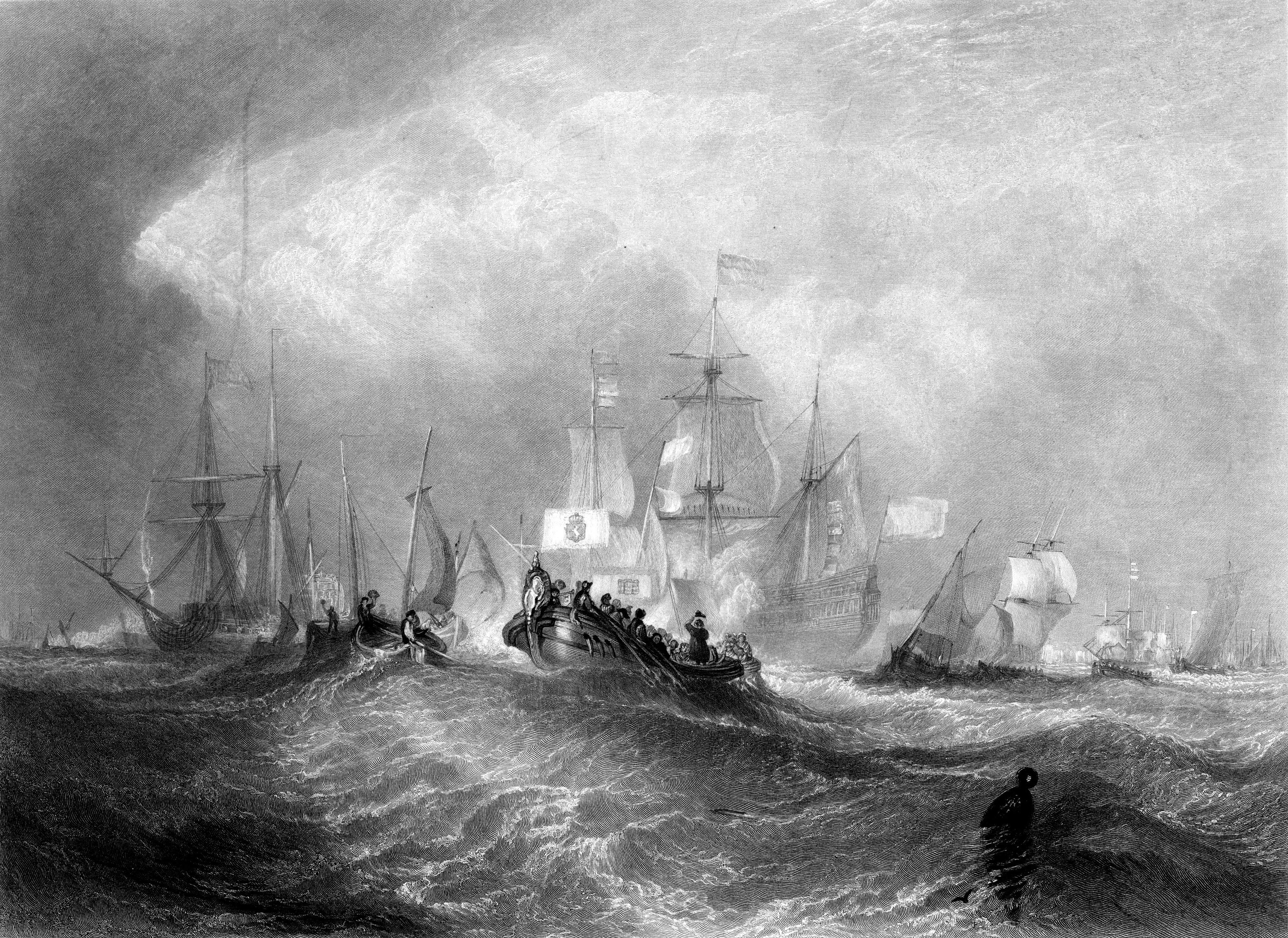

Battle of Naseby, by an unknown artist. The victory of the Parliamentarian New Model Army, under Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, over the Royalist army, commanded by Prince Rupert, at the Battle of Naseby (June 14, 1645) marked the decisive turning point in the English Civil War. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Then, we have the issue of the revolutionaries. In most of these cases, they didn’t know what was going to happen next. In 1642, when the English Civil War started and they just wanted more power for parliament, they ended up with Cromwell and the return of a Stuart. Eventually, they ended up with a Hanoverian king, in 1714. The Americans were not quite certain what the powers of the 13 colonies would be. As for the Bolsheviks, Lenin would not have known that there could have been a revolution, and he himself played it by ear. This is what happens in real history.

We have a national narrative which tries to pretend that everything was planned in advance – the French call it the Roman National – in which Bismarck had planned the unification of Germany, Lenin had planned everything and Mao knew what was going to happen next. But this is part of the ideology of State building.

A successful revolution?

We never know, in history, what we can call a success. Some things are successful for some people, but they are not for others. Unquestionably, the American Revolution was very successful from the point of view of those who wanted to run their own affairs without interference from London. It was not necessarily a success for the Indians, who were removed from their lands and secluded into reservations. It was not a success for the slaves in the American South, who went on being slaves and, even after the Civil War, remained second-class citizens. What revolution does is it inspires people to continue the work of the revolution.