Then, in 1945, as the United Nations Charter was being negotiated, the countries of the world decided that it was time to bring colonialism to an end. They negotiated a Charter, which contained two new rules: one rule articulated the proposition that every human being had minimum rights under international law. It coined the phrase “human rights” in modern parlance. The second new rule was a commitment of every country in the world to decolonise – for the colonial powers to leave their colonies and to allow the inhabitants of those colonies to exercise something that is known as “the right of self-determination”: being in charge of their own futures, deciding for themselves how they wish to be governed, and not being governed by outsiders or by others. That is the principle of decolonisation.

Closing the book on colonisation

Professor of Law

- In 1945, as the United Nations Charter was being negotiated, the countries of the world decided that it was time to bring colonialism to an end.

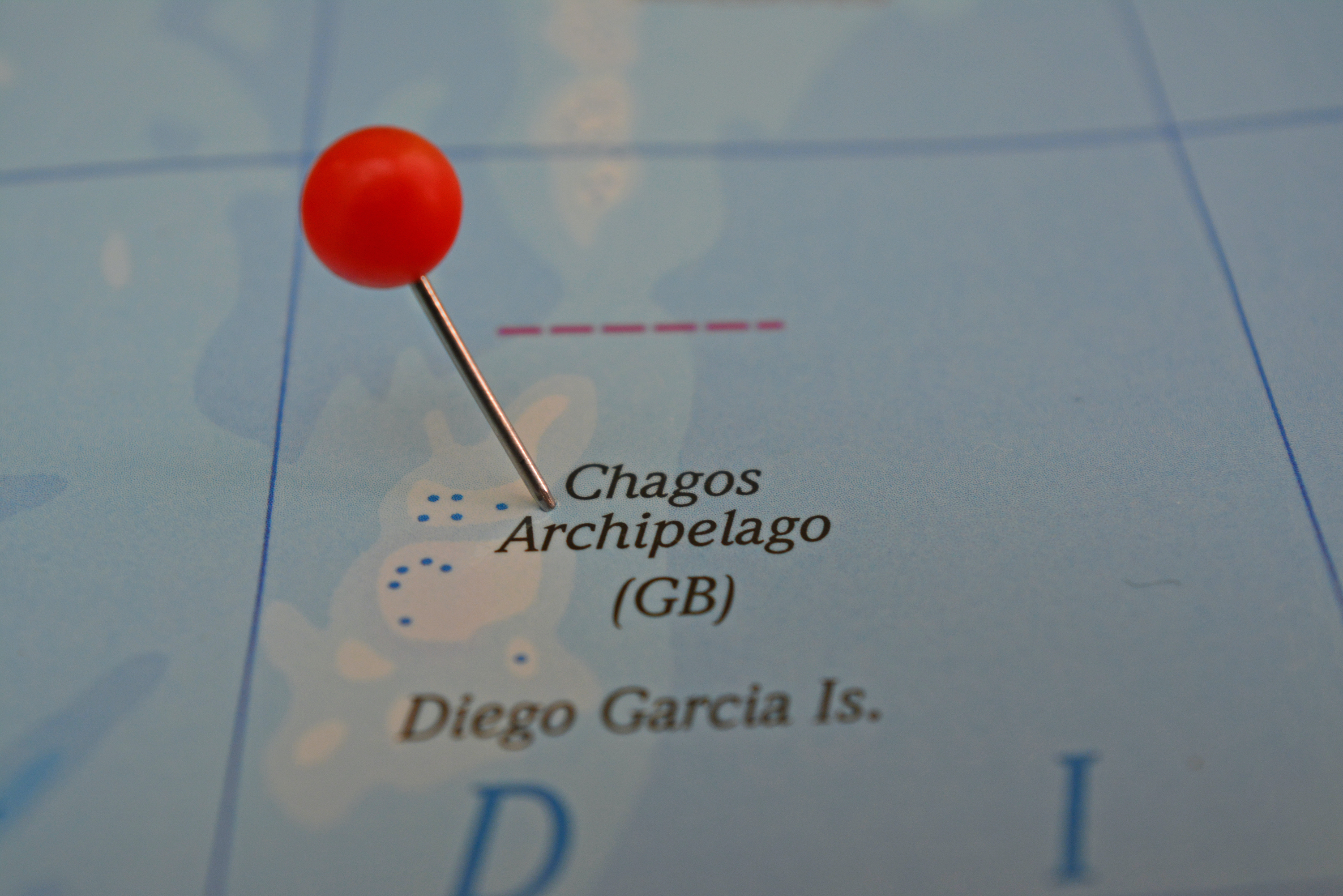

- There are still a small number of colonies that exist. Britain’s last colony in Africa is called the Chagos Archipelago, where the United Kingdom is an unlawful occupier.

- The devastating irony is that the United States and the United Kingdom created the rules that are premised around the United Nations Charter, but they have now upended those rules.

- On 3 October 2024—after this conversation was recorded—the UK agreed to hand over the Chagos Islands to Mauritius.

A commitment to decolonise

We all know that in the 18th and 19th centuries, European countries went around the world picking up bits of territory and colonising them. It was known as colonialism in Africa, in South America and in Asia. Spain, France, Britain, Germany, Italy, Denmark, Holland and various other countries were rather expert in this practice, which proceeded until the 20th century.

“WE THE PEOPLES OF THE UNITED NATIONS.” Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The legal framework

Today, there are about 200 countries in the world. Back in 1945, there were only about 50. It was one of those countries, the United States, that led the charge against colonialism. It was US drafters principally, and one man in particular, Ralph Bunche, a doctor who would be granted a Nobel Prize for Peace in 1950, who drafted the provisions of the United Nations Charter – a political direction, but crafted in legal terms – which committed all countries in the world to move generally towards decolonisation. It obliged the colonial powers to commit to withdrawing from their colonies. Over a period of 25 years, during that process of decolonisation, a political instinct was accompanied by legal rules to oversee that process. It has not been entirely completed, but more or less so, as of today.

How can reparations be made?

Photo by Sergey Shubin.

This is a very tricky question. If we take, for example, slavery, when slavery was perpetrated in the 18th and early 19th centuries, it was not prohibited by international law. It’s prohibited by international law today. One of the challenges that we have is that slavery, in the eyes of many, myself included, continues to have a legacy and consequences today. Those consequences are negative ones. They include acts of racism, including institutional racism in countries like the United Kingdom and the United States. One of the difficult questions is, how do you repair the damage that is felt today for acts that took place many years ago and were not internationally unlawful when they occurred? This is a temporal challenge for international law. It has not been resolved, but increasing numbers of people are thinking about this issue.

No compensation for victims of slavery

In 1945, the Nuremberg tribunal was faced with dealing with the consequences of discrimination against Jews and many others. In the case of the Jews, it’s known as the Holocaust. Germany and Austria, to a lesser extent, set up a system of reparations, including financial reparations, for the victims of the Holocaust. There’s been no equivalent in relation to the matter of slavery. There is, it could be said, a parallel, because when the Holocaust was perpetrated, international law did not criminalise the treatment of human beings in that way, just as, back in the 18th and 19th centuries, international law did not criminalise the treatment of human beings as slaves.

So, it may well be that with the requisite political will – and, of course, politics is always important in defining legal obligations – it could be possible to conceive of a means of offering reparation for the victims of slavery and of colonialism, just as millions were found to offer reparation for the victims of the Holocaust. The reality, of course, is that it always begins with an acknowledgement of responsibility for what passed, and the colonial powers have been hesitant to accept responsibility for their past actions. There are exceptions: three or four years ago, President Macron of France, perhaps somewhat unintentionally, acknowledged that colonialism was a crime against humanity. Britain has not made that acknowledgement.

Britain’s last colony

Decolonisation, as a process, has more or less run its course, but not entirely. There is a small number of colonies that exist. Britain’s last colony in Africa is called the Chagos Archipelago. The British call it the British Indian Ocean territory. It was, for a century and a half, a part of Mauritius, in Africa. In 1965, the British government decided it would give independence to Mauritius, but it wished to keep hold of the islands of the Chagos Archipelago, and it separated them. Mauritius obtained independence in 1968. It was decolonised, but it considered the decolonisation not complete, and for 50 years it has sought to recover the Chagos Archipelago from the United Kingdom, which has leased out one of the islands, Diego Garcia, as a United States military base.

I was hired about 10 years ago by the government of Mauritius to help recover the Chagos Archipelago. We designed a legal strategy based on those United Nations rules adopted in 1945 and, eventually, we managed to get a case to the International Court of Justice. The General Assembly of the United Nations made the request for the case, and in February 2019, the International Court of Justice ruled, unanimously, that Chagos belonged to Mauritius. The United Kingdom was an unlawful occupier, and it had unlawfully separated Chagos from Mauritius. Why? Because, said the International Court of Justice, decolonisation is premised on the right to self-determination. The right to self-determination includes the principle of territorial integrity. When you grant a colony independence, the whole of the colony is entitled to independence.

An illegal colonial occupier

In May 2019, the General Assembly of the United Nations determined that the United Kingdom must leave Chagos by November 2019. The United Kingdom has refused to do so more or less as South Africa refused for nearly 20 years to leave the territory of South West Africa, which is known today as Namibia. So, the United Kingdom is in manifest violation of its obligations under international law. It continues to be an illegal colonial occupier of the Chagos Archipelago and, in doing that, it is refusing to allow the 2,000 or so Chagossians – the original inhabitants of the Chagos Archipelago, who were forcibly removed by the British between 1968 and 1973 – to return. That, in the eyes of some, is a crime against humanity. This is the way in which the Nuremberg moment comes together with the moment of decolonisation. Crimes against humanity, self-determination, territorial integrity, decolonisation – these are all part and parcel of that extraordinary 1945 moment, and, ironically, it is the British and the Americans who created that 1945 moment.

The devastating irony

There are many ironies about Britain’s last colony in Africa. One of them is that it is Britain and the United States who are in a tiny minority of countries opposing the General Assembly resolution which determined that the United Kingdom must leave the Chagos Archipelago. I should mention that Mauritius has made clear that the United States base can remain at Diego Garcia, but that the Chagossians must be allowed to return.

The overarching, devastating irony is that it is the United States and the United Kingdom that created the rules that are premised around the United Nations Charter, and it is now the United States and the United Kingdom, certainly under the previous administration of Mr Trump, supported by Mr Johnson, who have upended those rules. It remains to be seen, in this next phase of the global order, whether the British and the Americans will come back to the table and support their own construction of 1945.

Photo by JoaoCachapa.

I should mention that the failure to do so is potentially very difficult, both for the British and the Americans. For example, in relation to the law of the sea, the British and the Americans criticised China for not giving effect to a ruling of the UN Law of the Sea tribunal on the South China Sea which rejected China’s claims to parts of the South China Sea. Similarly, a UN Law of the Sea tribunal has determined that the United Kingdom has no rights and no claim in relation to the Chagos Archipelago. But thus far, the United Kingdom has ignored it, just as China has ignored the other ruling. Of course, that raises the problem that Britain is not well placed to criticise China for its violations if it, too, is in violation. That is one of the ironies of the situation in which we now find ourselves.

The heart of the idea

The beating heart of the ideas of human rights and decolonisation is the notion that human beings as individuals and as a collective must be in charge of their own destinies. It is for them to decide how they wish to be governed. It is for them to decide the direction of their communities and the essential principle of the right of self-determination. The whole thrust of the idea of decolonisation is to avoid the imposition of values by one community on another community, that each of us must be autonomous in the community in which we exist, and that our community must be able to decide for itself the direction that it wishes to take. That is the fundamental heart of the idea of decolonisation.

Discover more about

human rights and decolonisation

Sands, P. (2016). Lawless World: Making and Breaking Global Rules. Penguin.

Sands, P. (2008). Torture Team: Rumsfeld’s Memo and the Betrayal of American Values. St. Martin’s Press.