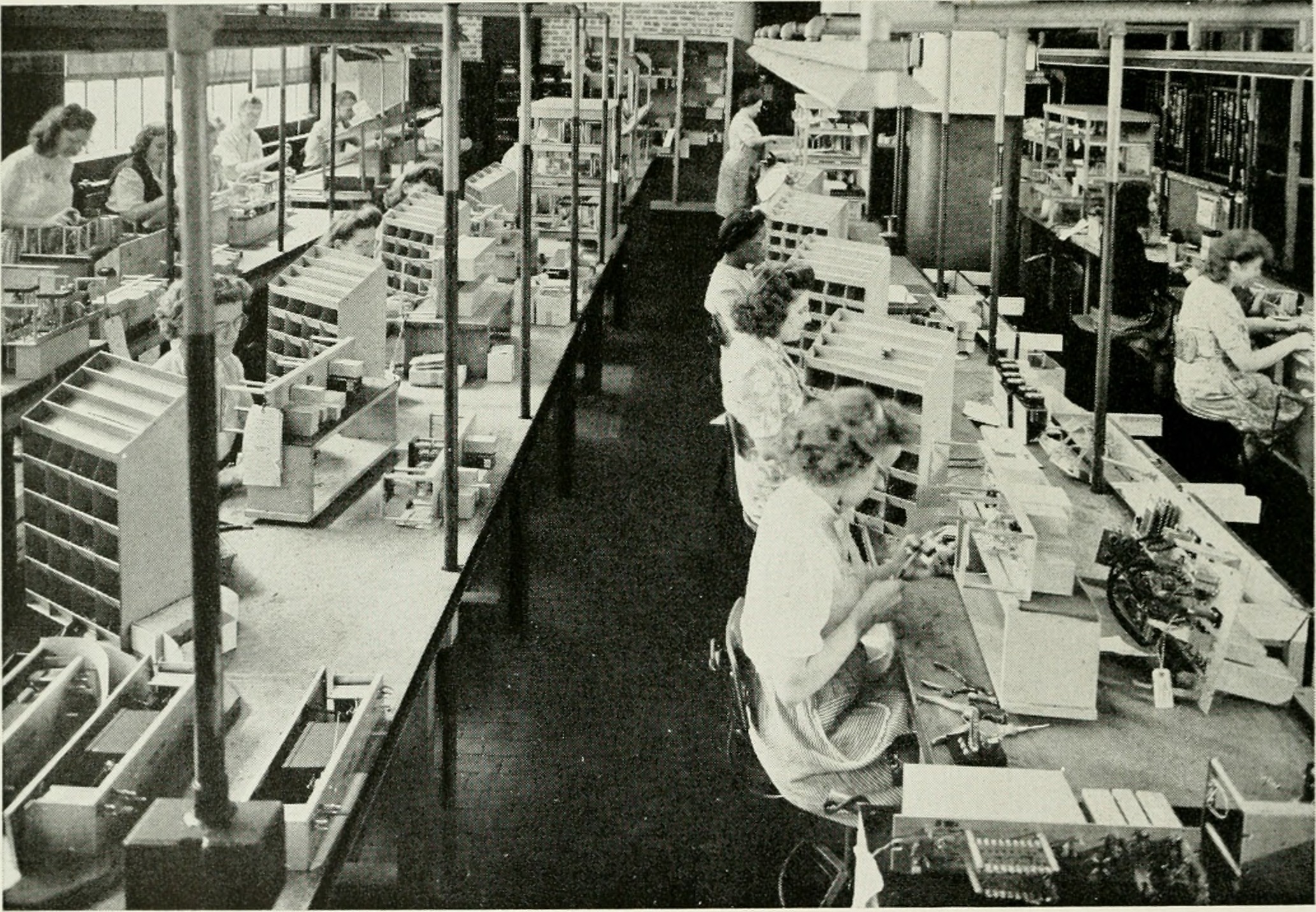

The development of capitalism as a global force, which is something that happens in the second half of the 19th century, is due to the exercise of State power. States were realising that in order to be strong, you needed to have a strong economy, and it had to be a capitalist economy.

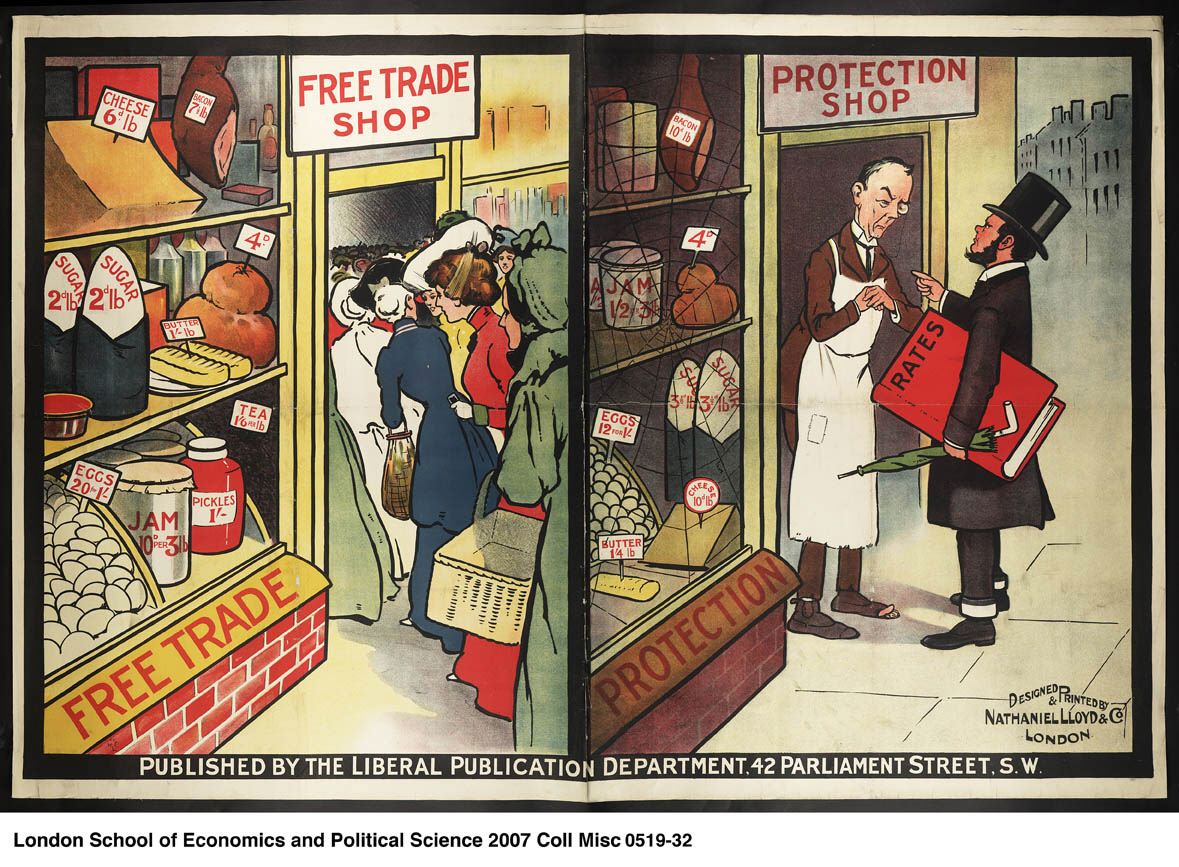

The most protectionist State in the 19th century was the United States of America. It was not a laissez-faire State at all. It was strongly interventionist. The second most protectionist State was Tsarist Russia. In other words, if your capitalism was not all that strong and if it needed to resist the competition from others, you needed someone, i.e. the State, to establish tariffs to protect you.