Bloomsbury has most often been seen as an icon of Euro-American modernity, where people lived in squares and loved in triangles, with famous names like Virginia Woolf, Leonard Woolf, Duncan Grant and Lytton Strachey. But as that movement was in full pelt, the streets were full of people from India and other parts of the Empire. India was in Britain just as much as Britain was in India. As Virginia Woolf put it in The Waves, ‘India is outside.’ In fact, India was in much closer proximity – next door.

Indian presence in Bloomsbury and in British literary history

Emeritus Professor of Modern and Contemporary Literature

- While Bloomsbury is often seen as an icon of Euro-American modernity, India was present in the architecture, languages, food, culture and politics of the area.

- Writers like Mulk Raj Anand and Tambimuttu had a bifocal perspective on Britain. Multilingual and well versed in Indian, Sri Lankan and British writings, they were world citizens before that idea came into vogue.

- The memory of Indian writers and their presence in Bloomsbury has often been erased. Not only are they seldom referred to in literary histories, but sometimes they are literally wiped out.

Key point 1

While Bloomsbury is often seen as an icon of Euro-American modernity, India was present in the architecture, languages, food, culture and politics of the area.

Key point 2

Writers like Mulk Raj Anand and Tambimuttu had a bifocal perspective on Britain. Multilingual and well versed in Indian, Sri Lankan and British writings, they were world citizens before that idea came into vogue.

Key point 3

The memory of Indian writers and their presence in Bloomsbury has often been erased. Not only are they seldom referred to in literary histories, but sometimes they are literally wiped out.

Multicultural Bloomsbury

© Some Bloomsbury members. A group at Garsington Manor, country home of Lady Ottoline Morrell, near Oxford. Left to right: Lady Ottoline Morrell, Mrs. Aldous Huxley, Lytton Strachey, Duncan Grant, and Vanessa Bell. 1915. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

When I say next door and when I talk about Bloomsbury, I’m talking about it as a materialist space, full of publishing houses, students attending university, people meeting in cafés and spice shops. India was present in the architecture, in the languages that were spoken and in the food that was eaten, apart from in the cultural life itself. It was also present, importantly, in politics, because there were a lot of political figures in Britain living in this area at the time. Most of them moved between the London School of Economics, which was at the bottom of the Strand, and University College London, which was in Gower Street.

The squares where the Hogarth Press and the famous Bloomsbury Group lived were also traversed by all these students, politicians and activists – and the underclasses who manned many of the restaurants – creating a composite world and a very multicultural, cosmopolitan space, which people aren’t really aware of. In fact, one of the early travel guides to Bloomsbury, produced by Ward, Lock & Co., describes the streets as full of languages. You couldn’t walk more than half a block without hearing 12 or 13 languages spoken.

Writer Mulk Raj Anand

There were many famous public intellectuals, writers and editors living on the streets. Mulk Raj Anand is perhaps one of the most famous. He wrote a book called Conversations in Bloomsbury, which was published belatedly as a kind of intervention into the fact that he’d been written out of history. When Anand disappeared after the Second World War, V. S. Pritchett famously said that he had disappeared, and it had been a long silence.

Anand had been living in Britain since 1925, and went back home in 1945. He mixed during his student days with the Bloomsbury Set. He liked to aggrandise himself and play at being the colonial puppy in his book Conversations in Bloomsbury. But he staged lots of semi-fictional conversations and, to some degree, real conversations with Leonard Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Bonamy Dobrée and many others.

He later went to work with George Orwell at the BBC, which was a more substantive part of his career. He was basically a communist. He was a key player in setting up the Progressive Writers’ Movement in 1935 in a Chinese restaurant in Soho, and he published many, many novels. In fact, E. M. Forster was to write the preface to his first novel, Untouchable, which is now a Penguin Classic and which got rejected by 19 publishers.

© George Orwell at the BBC, 1940. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

When I say E. M. Forster wrote the preface, I cite that to point not so much the idea of a white writer patronising this young Indian writer – which, of course, he was doing – but also to show the proximity by which their works were placed and remain placed in history. Orwell and Anand, at the BBC, wrote about 70 programmes together, and little is known of that story.

Poet and publisher Tambimuttu

Another writer – very different politically from Anand, who was virtually a communist and definitely a social realist – was a writer from Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, who was known as Tambimuttu. He launched a famous magazine called Poetry London, which featured some of Britain’s greatest poets and artists, including Henry Moore, David Gascoyne, Lawrence Durrell, Kathleen Raine and Barbara Hepworth. Tambimuttu believed in art for art’s sake, and he was seen as a real character around the place.

There were many, many comments on him at the time as an exotic ‘Oriental’. People liked to call him a snake charmer who lost manuscripts in taxis – he famously was supposed to have left one of William Empson’s manuscripts in a taxi. In fact, he didn’t lose the manuscript, and it has actually recently been republished.

Tambimuttu was key in publishing British poets rather than Asian poets, whereas Anand, who was much more involved with the Indian progressive writers, was concerned with focusing on Indian identities and Indian modernities, which he saw as running in parallel with what was going on in Britain. Both these writers really had a bifocal perspective on Britain. They spoke many languages. They’d read Indian, Sri Lankan and British writings, and they were well versed in all. They were world citizens well before that idea came into vogue.

Forgotten names of Bloomsbury

Interestingly, there have been a lot of erasures in the memory of these writers and their presence at the heart of the empire in Bloomsbury. Not only is it the case that they seldom are referred to in literary histories, but sometimes they’re literally wiped out. I have two examples of that. The first is in Robert Graves’s famous autobiography, Good-Bye to All That. Graves had a close relationship with an Indian philosopher called Basanta Mallik in Oxford, whom he met at the Lotus Club in 1922. When he wrote the first edition of Good-Bye to All That, he acknowledged Mallik as one of his friends; Mallik had supported Graves from his shell shock when he came back from the First World War.

Another example – and this is probably the most graphic example of how critics and critical movements can frame literary history – was the appearance of a photograph in the Times Literary Supplement (TLS) in 2000, the era of postcolonial writing. In a 2000 edition of the TLS, the editors reproduced a photograph taken from 1942, when George Orwell was together with a range of these Indian writers from Bloomsbury and its environs, as well as major British figures. In the TLS version of the photograph, the only names that were mentioned were William Empson, George Orwell and T. S. Eliot. All the other writers in that image, the original image which George Orwell had photographed, were called simply “others”. They were literally cut out.

The caption on this cropped version of the photograph reproduced in the TLS (2000) reads ‘gathered together among others, from left to right, T.S. Eliot, George Orwell and William Empson’.

Erased from history

Ironically, the particular feature that appeared in the TLS was called ‘How the Critic Came to Be King’. It was an article on Euro-American modernism. The original photograph, which appeared in 1942, took place on a poetry magazine programme called Voice, which was part of the BBC Eastern Service programme and output during the war. Many of these Indian writers and intellectuals featured on this programme on a regular basis, and their programmes were broadcast in India as a form of war effort to persuade the Indians that the British weren’t such a bad thing after all.

From ‘VOICE’ – 1942 BBC Eastern Service monthly magazine. (Left to right, sitting) Venu Chitale, J.M.Tambimuttu, T.S.Eliot, Una Marson, Mulk Raj Anand, C.Pemberton, Narayana Menon; (standing) George Orwell, Nancy Barratt, William Empson.

After the war, many of these Indians simply disappeared from British literary history, rather like, sadly, the many soldiers from India that took part in the Second World War, which was a multicultural theatre of war and involved many, many countries of the Empire. The Indian soldiers sadly lost their pensions because they were no longer seen as British, and once India received its independence, neither were they seen as Indian, ironically because they had supported Britain and had not been part of the nationalist mission, which had been led by a character called Subhas Bose in Germany. So, the Eastern Service programme, which was run by Eric Blair, a pseudonym for George Orwell, was in part set up to counter the nationalist programmes being broadcast by Berlin at the time.

A cross-cultural platform of modernity

In the photograph were people like Tambimuttu and Mulk Raj Anand. There was a female writer called Venu Chitale, who was to publish a novel in the 1950s, and other critics. But beyond the frame of that photograph, of course, you had the relationships between people like E. M. Forster and Anand, who were meeting Leonard Woolf, whose novel The Village in the Jungle was highly influential and impacted on figures like Anand. It was a centre for cross-cultural exchange, a contact zone, a platform for an international fraternity of writers, as Anand was to put it.

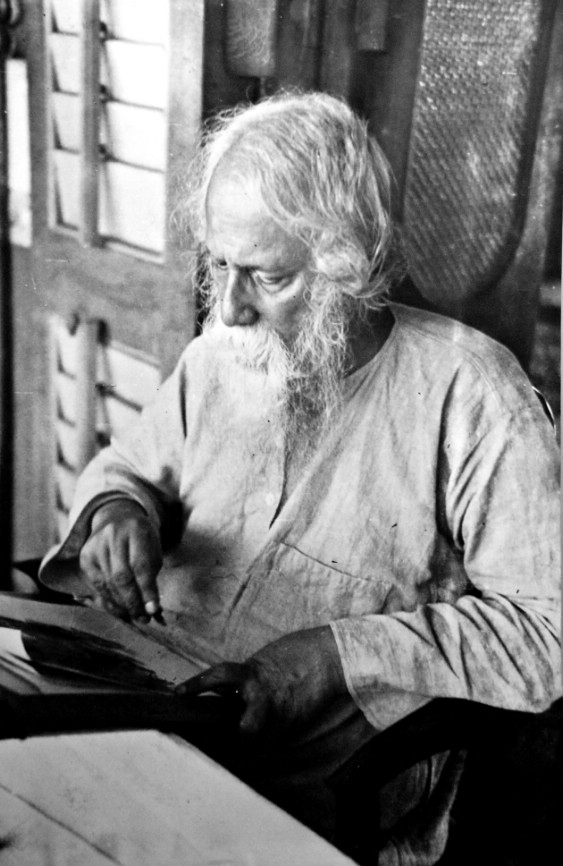

© Rabindranath Tagore reading (before 1941). Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The importance of India in Bloomsbury points to gaps in the ways in which modernity has been seen. Modernity has largely been seen as something stemming from a Eurocentric position. The proximity of the presence of the many Indian writers who were there in Bloomsbury highlights the extent to which these modernities were taking place in a coeval sense. They were adjacent. They were taking place in India at the same time as they were taking place in Britain, and there was a cross-relationship between these things. The famous relationship, for example, between Rabindranath Tagore and the Irish poet W. B. Yeats, who introduces Tagore’s famous poem “Gitanjali”, is a case in point.

Discover more

About the Indian presence in Bloomsbury

Nasta, S. (Ed.). (2013). India in Britain: South Asian Networks and Connections, 1858–1950. Palgrave Macmillan.

Nasta S. (2011). Negotiating a ‘New World Order’: Mulk Raj Anand as Public Intellectual at the Heart of Empire (1925-1945). In R. Ahmed & S. Mukherjee (Eds.), South Asian Resistances in Britain, 1858-1947 (pp. 140–161). Continuum.

Nasta, S. (2002). Home Truths: Fictions of the South Asian Diaspora in Britain. Palgrave.