The question of Woolf’s illness, a mental illness, and physical illness as well, is a difficult one. Her husband, Leonard Woolf, defined it as manic depression, and perhaps that is what it was. There is that sense of the highs and the lows, and certainly the great intensity of periods that she came to finish; all of the novels do seem to mark that sense of extraordinary intensity of perception, extraordinary intensity of the world. She also gives us characters like Rhoda in The Waves, or Mrs Dalloway in the novel of that name, for whom the world is a very dangerous place. She thought, she says in Mrs Dalloway, how very, very dangerous it was to live only one day. I do think those perceptions, the sense of the risks that are taken just in the very act of living, but also the very huge and extraordinary intensity of perception, of poetic imagination, does shape and colour her novels in profound ways.

The life and times of Virginia Woolf

Professor of English (1956-2021)

- Virginia Woolf was from an intellectual and well-connected family, and though she did not attend school or university, she had free rein of her father’s extensive library. She became one of the greatest 20th century novelists.

- There are indirectly autobiographical elements to her works, which also incorporate her ideas from Freud and the highs and lows of her undefined mental illness.

- Woolf created new names for the novel, new forms, flexibility and fluidity for identity and gender, and she experimented with different forms of storytelling.

New forms for the novel

Virginia Woolf, born as so many modernists were into the Victorian period at the beginning of the 1880s, was the daughter of the philosopher and biographer Sir Leslie Stephen. Born into an intellectual, very well-connected family, she did not attend school. She did not attend university, but she had free rein of her father’s extensive library and read voraciously. She became one of the very greatest of 20th century novelists, with work that began in perhaps the more realist tradition, though always realism with a twist. With her first novel, on which she laboured for many years, The Voyage Out, and then moving through to very different modes of novel writing – the fantasy world of Orlando; the play poem, The Waves; the one-day novel, Mrs Dalloway; her greatest novel for me, To the Lighthouse, and all the way through – she talked about needing to find new names and new forms for the novel. It’s the endless and surprising originality of her work that marks her for me as the great writer that she is.

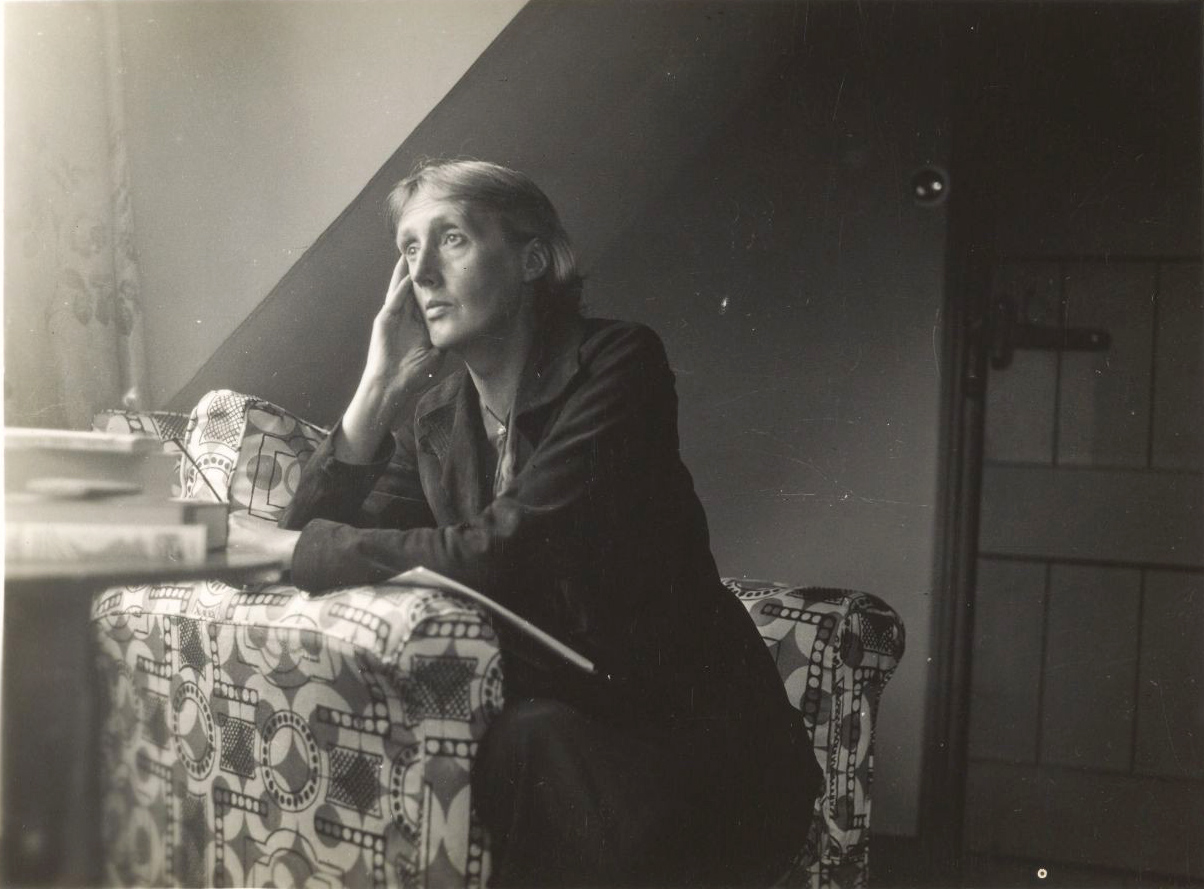

Virginia Woolf sitting in an armchair at Monk's House before 1942. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

An autobiographical core?

I think the question of autobiography in Virginia Woolf’s writing is complex. Her most directly autobiographical novel is To the Lighthouse, in which she talks of her mother and father, Mr and Mrs Ramsey, and elements of her own childhood, and in which she represents the early death of her mother and the desire to recuperate her in writing. She wrote of that novel that she did for herself what she thought psychoanalysts do for their patients, and that after she had written it she no longer heard her mother’s voice. ‘I no longer hear my mother’s love,’ she said. ‘She has ceased to haunt me.’ So there is a direct autobiographical link there.

When she came to write The Waves very few years later she said, ‘This should be childhood, but it should not be my childhood.’ So I think the autobiographical dimensions are often displaced rather than direct in her work. She did, of course, write her own memoir towards the end of her life, A Sketch of the Past, though it was not published in her lifetime. In that she asks the question, ‘Who was I then?’ It’s a very powerful meditation on that and also on the character of her mother and of her father, as well as her own feelings towards them.

Virginia Woolf and Freud

In A Sketch of the Past, which she was writing in 1939, she tells us it was then that she was first reading Freud. Curious, because The Hogarth Press, which she ran with her husband, Leonard Woolf, had been publishing Freud’s work since 1924 and her brother, Adrian Stephen, had become one of the first analysts.

Woolf wrote her memoir as she was reading Freud, and the word that most struck her then was “ambivalence” – a new word for her in the language, which she used to think about the admixture of love and hate that she felt for her father in particular. I think it resonates with all her novels where characters oscillate between conflicting emotions: the pull of “I love” and “I hate”. It goes back to that sense of the instability, the sense of the multiplicity and of character that is so central to the modernist text.

Virginia Woolf’s illness

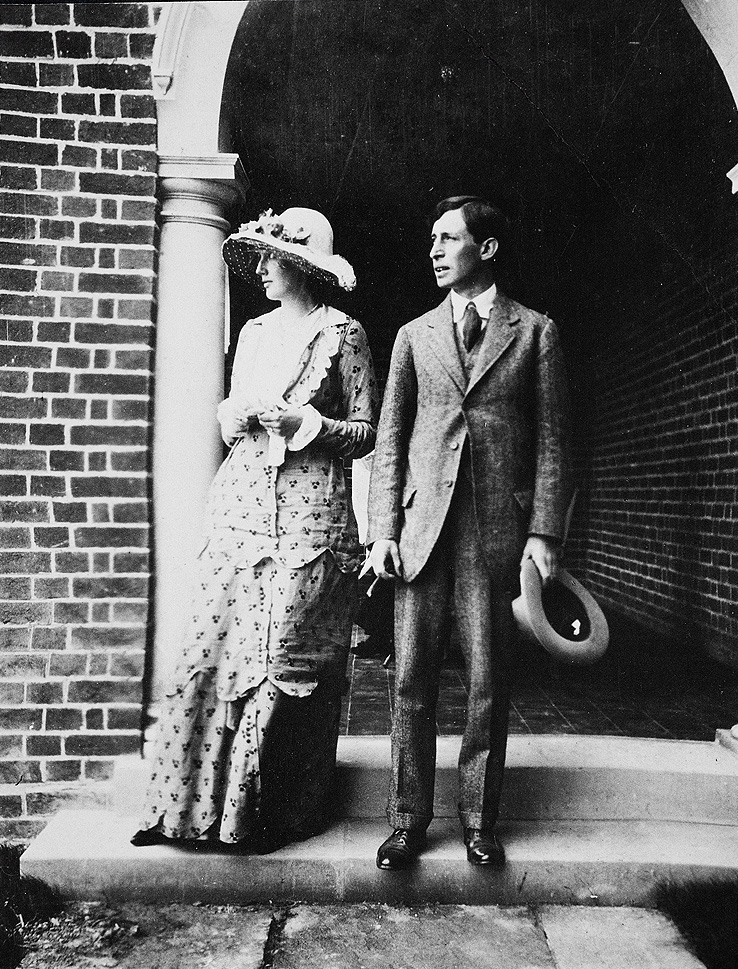

Engagement photograph, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, 23 July 1912, a month before their wedding. Photograph taken at Dalingridge Place, the Sussex home of Virginia’s half-brother, George Duckworth. 1912. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Defining a new moment

The sense for Woolf of creating new names for the novel, of not being satisfied with the forms that it had taken, shapes the modes of novelty that will colour the novels that come after her. She said, in Mrs Dalloway, ‘I have discovered my tunnelling method by which I will tell the past in instalments,’ so, more broadly, the interrelations of past and present, the workings of time and memory, came to be very central to the modernist text. We think of Proust, who is such an important figure for Woolf. Other strategies include the one-day novel, and we think again of Mrs Dalloway but also of Joyce’s Ulysses, the sense that all life is contained in that one day, but the one day is opening out to much larger worlds of experience and imagination. She uses a mixture of forms, so the sense that you can write a novel as a play poem or that you can bring the worlds of film and photography into your texts. I believe Woolf does that in her writing and then that becomes an incredibly important strategy in later works.

New terms for women’s lives

Woolf becomes one of the most important 20th century writers in part because she gives us new terms for thinking about women’s lives. The late 19th and early 20th century “New Woman” novel is concerned with women’s development. The development usually of the young woman, whereas in a novel like Mrs Dalloway Woolf is as concerned with the older women, the middle-aged woman who has already made her life choices but must go back to consider how those were made and how she came to live the life that she did. In Orlando, a very different text, she shows us a figure who lives first as a man and then as a woman. That sense of the fluidity and flexibility of gender identity has been a hugely important influence to texts that came after her, though there was also a feature of other writers of the modernist period. If we think of the American writer Djuna Barnes, she would be another writer who plays with gender identity, undoing many of the fixities of identity, of sexuality, of being in the world that had come to characterise the 19th century text.

Cinema and Virginia Woolf’s modernism

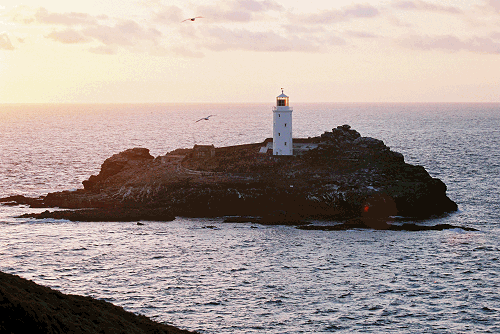

© Credits

Virginia Woolf wrote one of the most prescient and interesting pieces of writing on the cinema in an essay of 1926 called The Cinema. It was written in some ways against the current mode of adaptation of fiction. She was not keen on this, seeing the cinema becoming parasitic upon the novel, but she was also very interested in what the cinema might become if it left those source textbooks behind and began to develop its own language, its own way of seeing the world, its own aesthetic. She was working on The Cinema as she wrote the central section of To the Lighthouse, “Time Passes”, after the family holiday home has become empty following the death of Mrs Ramsay, and the world is seen without a self. Film, one could say, sees the world without a self. It is a world of objects, of stray airs, of the ways in which time shapes and wreaks havoc upon the things of the world. I believe Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, in particular, to be a profoundly cinematic novel and a novel that is caught up in the new experimental possibilities of what film might do. At the end of To the Lighthouse, Woolf experiments with simultaneity. Instead of the linearity of the novel, she attempts to give us two things happening: the artist figure Lily Briscoe completes her painting at the same time Mr Ramsay and the children take the trip to the lighthouse that was planned but not completed at the beginning of the novel. I think we might think of this as the kind of simultaneity that film was able to achieve by moving between two scenes or even by giving us a split screen. She was interested in those technical possibilities and how the novelist might use them for his or her own purposes.

Woolf’s use of language

Woolf is an extraordinary prose stylist. Her prose is rich and dense, experimental, highly coloured in some ways. She was a self-conscious stylist, and sometimes she even parodied her own lyrical mode so that, in Orlando, we get a pastiche almost of the lyrical, poetic dimensions of To the Lighthouse, where she’s exploring the world without a self. I think that, above all, Woolf is a writer who gives us very many different kinds of styles and is always acutely conscious of the way words work upon the world.

Woolf was a writer who was hugely conscious about the way words work, and she actually produced a radio broadcast on the very topic of words and their appeal to the senses. Words for her multiply sensory appeal to the ear, to the eye, to the sense of smell. She experimented with different kinds of writing. Sometimes she even parodied her own lyrical modes and styles. She was a writer who was capable of moving between different styles, and I don’t think there’s a single way in which I would characterise Woolf’s work except that it has an extraordinary power to move as well as to delight us.

Discover more about

Virginia Woolf

Marcus, L. (2017). “Some Ancestral Dread:” Woolf, Autobiography, and the Question of “Shame”. In J. deGay, T. Breckin, & A. Reus (Eds.), Virginia Woolf and Heritage (pp. 264-281). Liverpool University Press.

Marcus, L. (2012). Virginia Woolf (1882–1941): Re-forming the novel. In M. Bell (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to European Novelists (pp. 378–393). Cambridge University Press.

Marcus, L. (2011). Virginia Woolf and Digression: Adventures in Consciousness. In A. Grohmann, & C. Wells (Eds.), Digressions in European Literature (pp. 118–129). Palgrave Macmillan, London.