The novel, alive and well

I think the state of the novel is extraordinarily healthy, whereas in the later 20th century, there were discussions of the death of the novel, or the American writer John Barth writing about the literature of exhaustion, the sense that it was a form that had run its course. If anything, I think it's more vigorous than it's ever been. Of course, the world of literature for us as Western readers has massively expanded as we’ve become aware, often through translation, of the plethora of fictional forms coming from every region of the world, so that our world is expanded into global literatures.

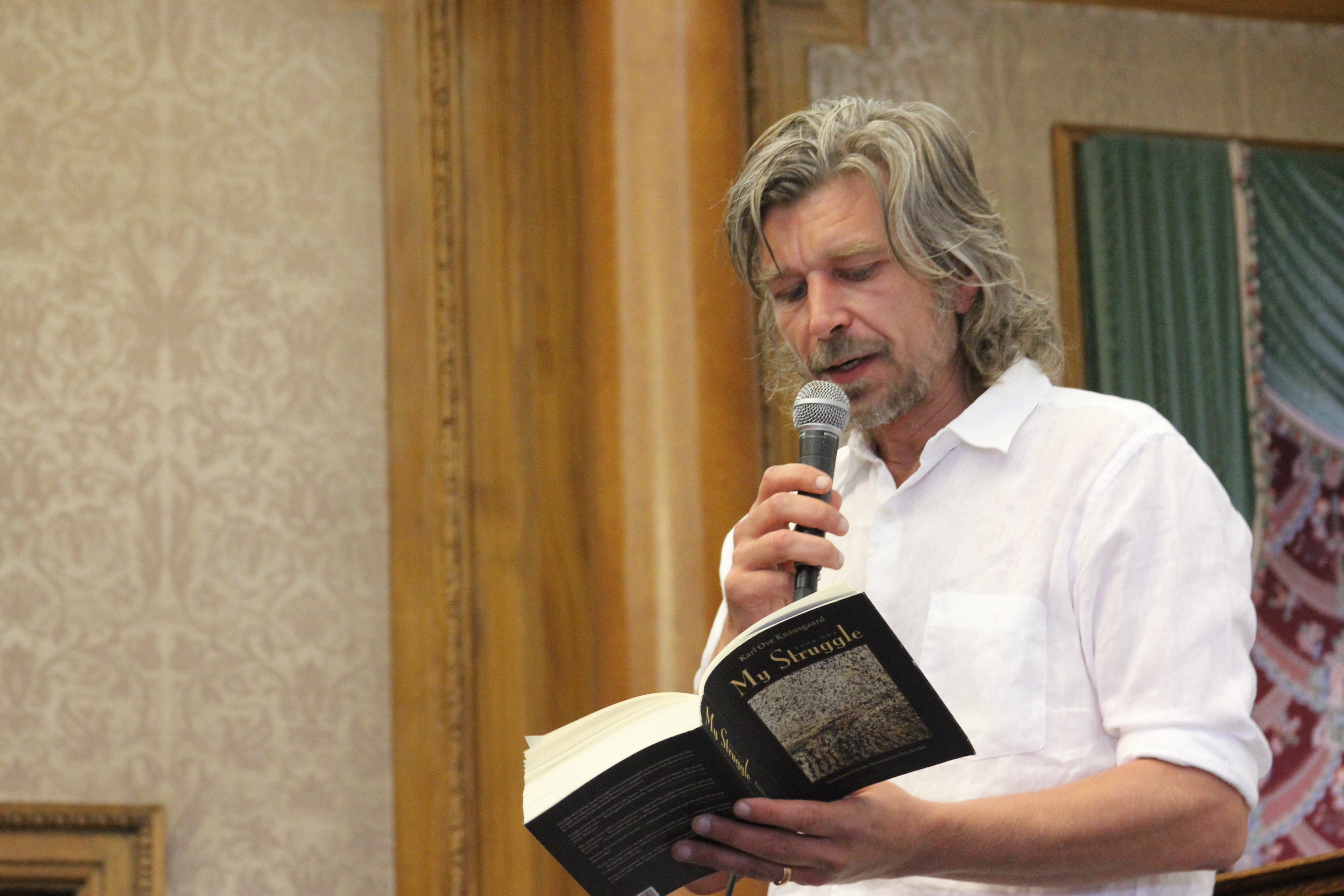

The world of the novel cannot be characterised in any single way. I don't think there's a single dominant form, though we might point to some new or recent developments and strategies that writers are applying and using. I'm interested, for example, in the mode of writing called autofiction, which one could say is a sense that has been developing since the mid-20th century. There is a kind of unease about the making up of fictional characters, a sense that what the writer should be writing about, as the British 20th century novelist B. S. Johnson said, should be a commitment to the world inside his own head. I think that admixture of fiction and autobiography that is coming through in autofiction is particularly interesting. We're finding that in the work of a great many writers in an Anglo-American context, including Rachel Cusk, Sheila Heti and Chris Kraus and, above all, the Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgård, whose extraordinary volumes of autofiction have been hugely popular. We move there between a sense of the fascination of fiction but also the sense that actually it's the story of the self that is, above all, interesting.

The development of the African novel is particularly interesting and important because it’s a relative latecomer to the scene. In the 20th century, the Latin American novel became perhaps the most powerful embodiment of fictional form with the development of magic realism, and that has, to some extent, continued today. The Indian novel of the contemporary period, which often takes Western forms of fiction but turns them to very different ends to show the world in a new light, would be another important example.

Postmodernism and its effect on fiction

Postmodernism developed as the key term from the 1960s perhaps through to the 1980s. It signalled a sense that modernism had run its course and that something else was taking its place. This was not just in literature, because the term was applied in architecture and art, as well as in other forms. There were also the ways in which modernism and postmodernism were polarised. To take one central example, the critic Brian McHale said that the difference was between the epistemology of the modernist novel that has caught up with the realms of knowledge, of consciousness, of subjectivity, and the ontology of the postmodernist novel, a concern with a question of being, with the question of world-making and world-construction as in Thomas Pynchon's line in The Crying of Lot 49 where he has his heroine, Oedipa Maas, saying, ‘Shall I project a world?’ That is one way of characterising it.

Postmodernism was also seen as self-reflexive, as a form of pastiche. I think the problem with that is that many of those terms could equally be applied to the modernist novel, and postmodernism had to create a rather rigid account of what modernism was in order to differentiate itself. I believe we've now, as it were, moved beyond both the period and the conceptual interest in postmodernism and are seeing a much more flexible account of what the contemporary novel is and can do, which draws on modernism as much as it draws on those modes developed in the mid and late 20th century.

There has been a great deal of interest amongst contemporary writers in returning to their modernist predecessors. For example, there is Zadie Smith, whose novel on beauty is written as both a homage and a pastiche of E. M. Forster's Howards End; or Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty, which rewrites the Jamesian novel, using the oblique language of Henry James to describe gay sexual encounters in ways that James himself could never have made explicit; or Colm Tóibín's wonderful The Master, which is a fictional biography imagining the life of the master of fiction, Henry James.

The writings of the one-day novel of Ulysses and Mrs Dalloway have been hugely important. Mulk Raj Anand's Untouchable is an early example of Christopher Isherwood's A Single Man, through to contemporary takes on it like the Indian writer Amit Chaudhuri’s Odysseus Abroad which rewrites Ulysses from the perspective of a young Indian student living in London. I would see this as a way of contemporary writers saying, ‘Actually, the modernist novel is by no means dead to us, as postmodernism is in some ways. We've moved beyond this. These are still the rich resources for our fictions.’ As I've suggested, the relationship to them is complex. It is both a homage and sometimes the pastiche or parody of that world of the early 20th century, showing its difference from as well as its likeness to our world of today.

Psychoanalysis and contemporary fiction

I think the way in which psychoanalysis has entered into contemporary fiction is rather different from the way it entered into modernist fiction, where it had entered with the sense of the complex psychology, with the multiplicity of self and the importance of dream worlds, as in Joyce's Finnegans Wake. I think it's coming through most strongly in the contemporary novel, rather obliquely in the fascination with the telling and the transmission of stories. I would take two examples here. The great late W. G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz, where Austerlitz tells his long and complex story to an unnamed narrator, and Rachel Cusk's Sebaldean, as I see it, The Outline Trilogy, except you’re aware how her narrator becomes a conduit, a mediator, a transparent vehicle to some extent for the all of the stories in the world, which she is sometimes the unwilling recipient of but which she passes on to the reader. I would see the psychoanalytic element there, not so much in Oedipal structures or a fascination with sex and interest in sexuality, but in the sense that we are made up of the fictions that we tell about ourselves, that we tell of others and that we communicate to the reader.

The relationship of film to fiction in the 20th and 21st centuries is hugely important. It is the writers, I think, of the mid-20th century onwards who were most interested in it. Writers like Doris Lessing, John Fowles, Muriel Spark were all very caught up in the world of film. Virginia Woolf was concerned about the parasitic quality of film on the novel through adaptation. There was an anxiety in some ways that film would displace the novelist, but also an awareness that we, all of us, as they saw it, see cinematically and that a writer is going to be representing the world that he or she represents in ways that are highly influenced by film with its own strategies, its close ups, its jump cuts, its looping, its chronology.

In the contemporary novel, there is very often an explicit incorporation of works of film or video into the text. I would single out the American writer Don DeLillo, who very often brings films into his texts, or the contemporary American writer, Ben Lerner, who has done the same things. These are writers who are fascinated by questions of perception, of attention but, above all, of time: how the novel sequences time and for film, with its own sequencing of time, but also its illusory interplay between stillness and motion. Film is an illusory medium, of course, because we see movement where there is none. It's a trick of the eye in many ways. I think writers are caught up in that sense of how you move from one moment to the next. How do you move from one scene to the next? What are acts of attention and how do they compose the fictional world that we read and are also a part of?

The draw of fiction

There is a great interest at the moment in the ways in which we immerse ourselves in the fictional world or that we can immerse ourselves in any work of literature. I do think the power of fiction for me is in those immersive possibilities to enter other worlds, worlds that are like our own and worlds that are unlike our own, and they enlarge us. They make us more than we are, and we are changed by what we read. I think the great novels are those where you are, at the end of them, a different person from the one that you were when you entered into that fictional world.