Of course, many people will be simply repeating what they have heard elsewhere. It could be propaganda. It could be something given to them by a commanding officer, or in some cases, even a parent or a loved one. What we often see within personal accounts by combat soldiers is an attempt to craft a language that feels right, accurate and truthful to them as they are experiencing the chaos of a battlefield.

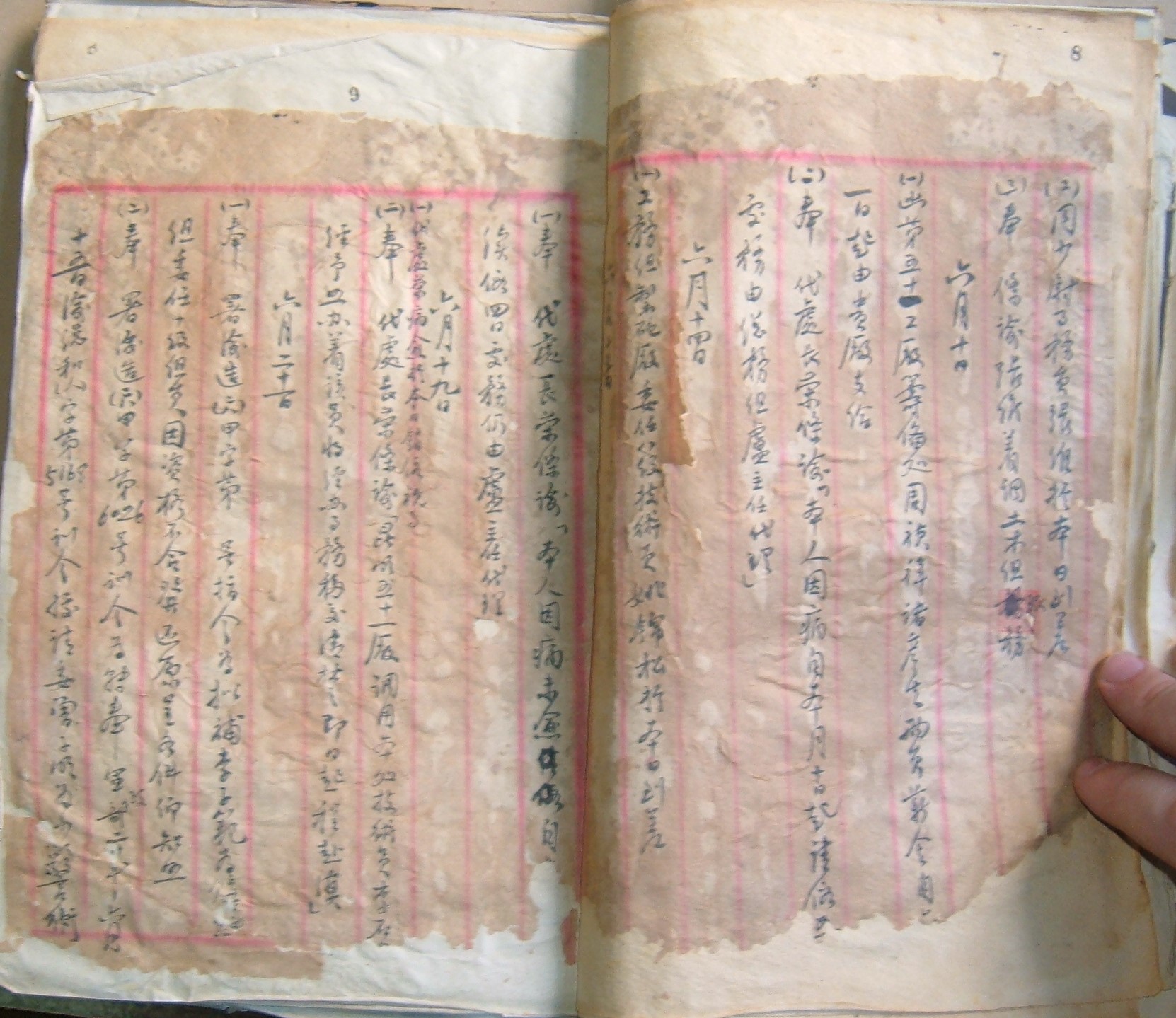

Soldiers' diaries in WWII

Handa Chair of Japanese-Chinese Relations

- Soldiers’ diaries are valuable not because they reveal inner truths but because they show the linguistic tools people used to make sense of war and survive it.

- These writings help us see how individuals absorb, reinterpret or resist state and media messaging, revealing the limits and possibilities of personal agency.

- Diaries can be dangerous because they can convince the writer to take harmful actions and later become a painful or inescapable record of the self.

- The act of diary writing was shaped by education and institutional practices, and it became a way for ordinary people to participate in larger political and cultural processes.

Why read soldiers’ diaries?

One of the reasons why it is useful to look at the diaries and overall life writings of ordinary soldiers, as opposed to military or political leaders, is that it helps us understand how people like us got involved in supporting modern warfare. This does not mean that we should be thinking about diaries as some kind of window into the soul or a unique perspective on truth but rather as linguistic tools people used to get them through the conflict.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

Personal voice and responsibility

What that shows us is that people are pretty capable of reinterpreting all of these powerful voices and messages that they get from the state, from the mass media or from the broader society and culture. That allows us to talk meaningfully about individual responsibility. That does not mean, for example, that every person has total freedom in self-expression. The toolkit they receive is a byproduct of the ways in which they are educated and the ways in which they grow up.

When we look at a diary — particularly by someone who is not very famous, who is not thinking about posterity when they write and who is not trying to craft some masterpiece, but who is simply writing down as accurately as they can what is going on around them and trying to give it some form of coherence — what we can do then with that document is illuminate many of the institutions and practices, and indeed technologies and media, that made that whole diary possible.

How soldiers recorded experience

Opening the diary is like opening the lens of a telescope and looking out into a broader world: how they were taught to capture factual information in a document, where they are in the world geographically, what the weather is like, how many soldiers there are, how many bullets they have, how much food they ate, how far they marched, where the enemy is, how many times they engaged with the enemy — I could go on and on.

On top of that, we also see the narrative styles they have imbibed from the literature that surrounds them at the time. It could be adventure fiction; it could be reportage. In many cases, though, they feel that these more traditional military styles of writing are really impoverished when it comes to capturing what it feels like at the time, so they reach into other areas as well. It could be poetry; it could be religious discourse.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

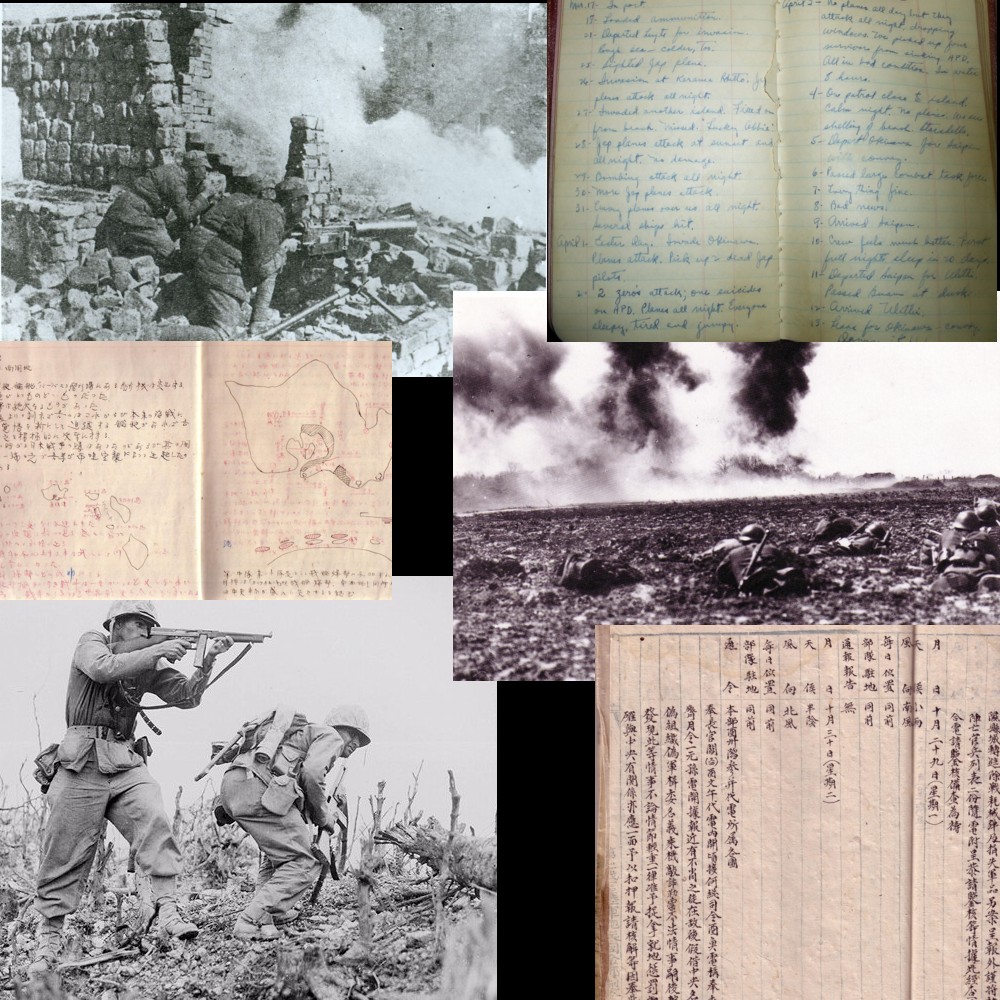

That bricolage they put together shows us the way in which people exercise agency in description. The diary itself is not for the author a soulless delineation of fact. It is a narrative that feels truthful to them. They may be drawing from reportage to expose hidden evils in the world or to show the heroism of their comrades. That gives us a much better idea of how truth is constructed in a document, rather than simply saying, the author may or may not have thought it was true.

Ordinary people are a little more guileless than professional authors. Looking at the ways that ordinary people write, we get a good idea of what kinds of documents were in circulation at the time, what kind of propaganda seemed to be working and what propaganda they may have been ignoring or critiquing. The more we get to the bottom of that, the more we can understand why people were committed to fighting — or why, in some cases, they gave up on war as a noble pursuit.

The diary as a dangerous space

It can seem a bit curious that I would describe something so innocuous as a diary as something that is very dangerous. Think of it this way: if you have a document that you believe is private, truthful and reflective of who you are as a person, then anything you write in it can potentially convince you to take a course of action that might be violent, either toward yourself or others.

It can lead you down a path of committing what would later be called a war crime. It could put you in harm’s way. It could lead you to make a decision like signing up for the army in the midst of a losing war. So the diary itself, because so many people accept them as truthful accounts, then becomes a very perilous space.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

If you are getting messages from the mass media that encourage men to define masculinity in terms of violence, and you write that down in your diary and accept it as a reflection of who you are, then you are convincing yourself to take that course of action.

The aftermath of writing

The more you record about yourself in a diary, the more you have to account for to yourself later. If you convinced yourself that becoming a kamikaze pilot is a noble way to end your life, you may find in the 1960s that that is a very painful side of yourself to confront.

One of the things that happened in societies around the world — famously in Japan — is that after the war, many people burned their diaries. They were not necessarily doing this out of fear of what the American occupiers would do with them or because they were ordered to, although the Japanese state did often ask soldiers and officers to destroy their records. They also destroyed them because they did not want to do the self-reflection that would come after the war.

Once you record yourself factually in a diary, it becomes an inescapable self — a haunting doppelganger that is going to pursue you into the postwar period. Most people who seem to have adjusted well after the war were the ones who destroyed the records of what they did during it, because that allows them to make up any story they like and reinvent their personal history. Honestly, that is a pretty good way to adapt to a new political environment. So, writing a diary can be dangerous on multiple levels.

Comparing soldiers across nations

I decided to combine my analysis of diaries using Chinese, Japanese and American soldiers during World War II, and the best way to explain why is through a short narrative. I began with Japanese soldiers, and one reason for this was that when I was living in Japan in the 1990s, there was a wave of publications and famous court cases involving Japanese soldiers. They were being sued for libel and slander and would provide diaries as evidence of their claims. That fascinated me, so I started reading many of these accounts. I realized I wanted to hear what their enemies were saying.

The war between China and Japan begins in 1937. What I found was that Chinese soldiers were writing in a very similar way to how the Japanese were writing. That explains why I would want to compare them, because they were fighting each other. It is interesting to put them in the same place at the same time, which I do occasionally. When I am lucky, I can find them literally on the same battlefield (even though their records come from different archives) and see the different ways they narrate those battlefields.

I had an intuitive suspicion that Americans were doing the same thing. I strongly suspected that I would find Americans quite capable of self-sacrifice, of listening to authorities and making the same kinds of dangerous decisions that Japanese and Chinese soldiers were making. That is precisely what I found. There are some differences and exceptions, but largely, ordinary people in China, Japan and the United States were able to sacrifice themselves for a collective endeavor of committing mass acts of violence. Part of it was me, as an American, confronting my own nation’s and culture’s capacity for doing much the same things as the Japanese and Chinese during a period of total war.

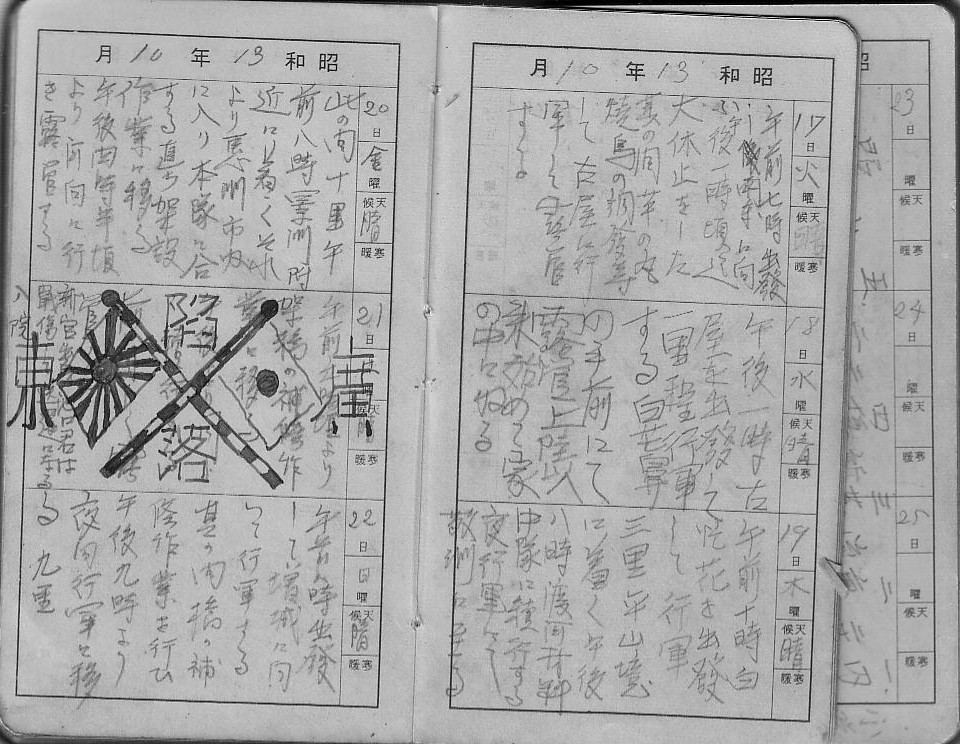

Diary writing as self-discipline

In my first book, I talk a lot about the concept of self-discipline. In using that term, I am engaging with philosopher Michel Foucault, who introduced historians to how important disciplinary apparatuses are in the modern state, much of it having to do with how modern institutions punish the soul. That is, they make people internalize certain kinds of messaging to direct the masses toward particular behaviors.

I was more interested in how individuals process this messaging rather than focusing only on the state, media or religious institutions. That was a consequence of me reading diaries.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

Diary writing is not something people do from nothing. They have to be taught how to do it. The modern state was particularly interested in encouraging people to write about themselves. You can see this most dramatically in the modern education system, where self-writing was something taught to children from a very early age.

People like to joke that it was just a composition exercise, and no one took it seriously, but the fact is, teachers were instructing children all the time — I was educated this way as well — to write about themselves as a way to learn language. In doing so, they emphasized: tell the truth; capture facts; describe things as they actually are.

If you add to that the practices of military record-keeping, which probably originated in Prussia and Britain, especially in the navy, there is a long history of documentation that converged with this kind of self-discipline.

Diaries as political tools

The ordinary person's story is more relevant than ever. People begin to develop a language of experience that allows them to articulate their daily lives with the assumption that those lives matter. At the same time, you have mass political movements — fascism, socialism, democratization — taking place. Ordinary people are starting to flex their muscles and make their voices heard. So, how does this bear on self-discipline?

It means that people have been taught to write accurately about themselves, to capture facts, to believe that their stories matter and to see themselves as part of broader political and cultural processes. Although the state can teach people these tools and techniques, it cannot control them. You can give someone a hammer, but they might sculpt with it — or smash something. The tool has many uses.

That fascinated me, because it means we do have some control over crafting who we are. We are not entirely shaped by those in power. There are limitations, yes, but we have been taught to craft ourselves in particular ways, and we should take that process seriously as a form of self-discipline.

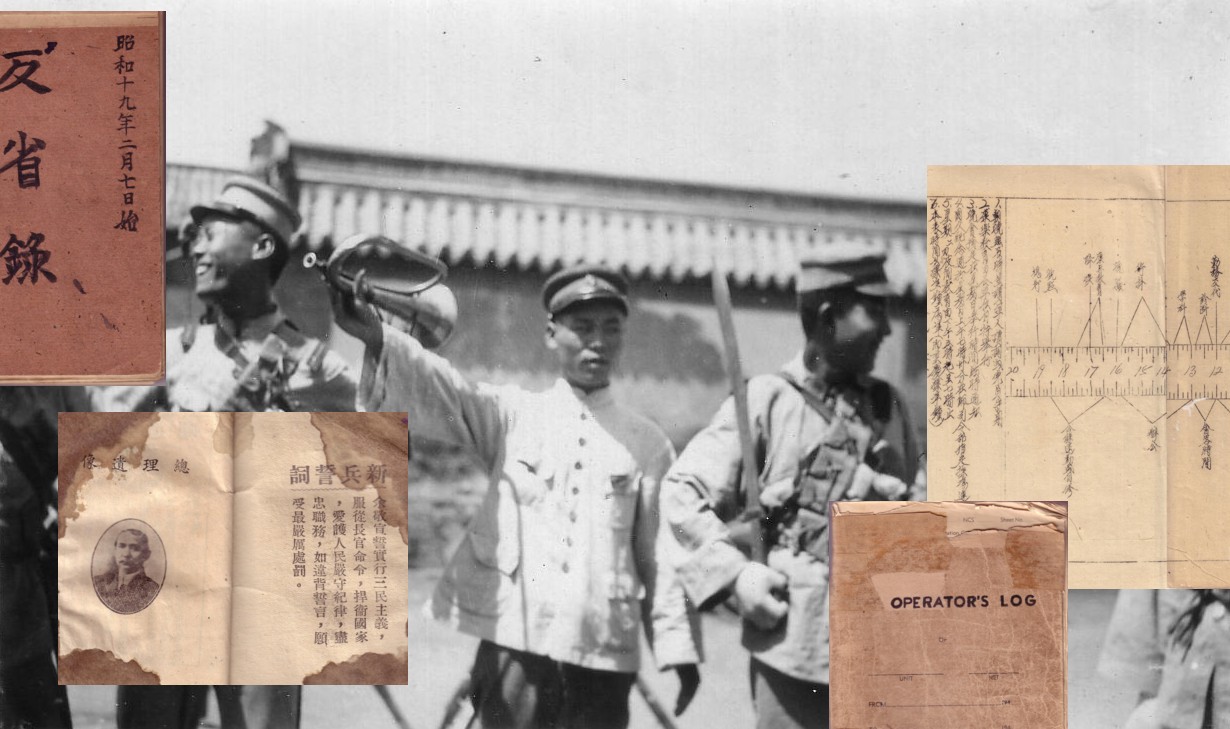

Trusting the diaries?

When we look at diaries, there is a temptation to ascribe a truth value to them. Is this diary reliable? Was it written for someone else? Were they not afraid of censorship? Often when we ask those questions, we bring unverifiable assumptions, such as that we can know what the author’s intention was — but we are not mind readers. Authorial intention is really problematic.

With a diary, which is a special document written over time and usually not re-edited, we often find that the author’s intention shifts over time. There is not a single, consistent intention driving it.

We are talking about people like you and me who do not have a mass audience. Who do they write for? It is not always clear. The intended reader can change.

Writing it down

What really struck me in retrospect was how hard each diarist worked simply to understand what was happening. That may seem like a simple or unexciting conclusion, but the fact that they wrote nearly every day, even about terrible things like losing a friend, losing a limb, being sick or witnessing or participating in atrocities, speaks volumes.

They felt a compulsion to write it down, and then afterward, to make it make sense — to give it coherence in a narrative that included them as an acting subject.

A soldier’s final words

I have a diary by a Chinese officer named Liu Jiaqi. It was published in October, 1938, in Wuhan. At that time, the city was under heavy Japanese attack. Liu was already dead, but the publishing house — briefly operational before the city fell — published his diary, because they believed it would inspire continued resistance.

Liu, even though he was a commanding officer and a graduate of one of China’s top military academies, was full of doubt. He had to confront the possibility that China would lose the war, and he would fail personally.

He wrote: "The officers and men in this division are not making any efforts in building our outer defenses, and more than a few cannot follow the basic regulations. I am deeply concerned about this. I am good at cultivating a spirit of meticulousness during a period of peace, but once we get our orders, it is not such an easy thing to do. From here on out, regarding our fighting spirit, if we are not resolved to die in battle, it is going to be extremely difficult to achieve victory. The officers and men in the division are spineless. Our system of punishment and reward isn't clear. And I'm truly concerned about our battle against the Japanese."

Liu went straight to the battlefield, fought and was machine-gunned by the Japanese. He died. What I find powerful is what happened afterward. In the postwar period, the local Wuhan government tried to name a road after him. During Maoism, the road was renamed — first Liao Zhongkai Road, then Red Guard Road and so on. Only after Maoism ended were they able to rename the road after Liu Jiaqi. You can still visit it today — but I am not sure how many people in China remember his name now.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

Soldiers' Diaries

Moore, A. W. (2013).Writing war: Soldiers record the Japanese Empire.. Harvard University Press.

Moore, A. W. (2017). Reversing the gaze: The construction of “adulthood” in the wartime diaries of Japanese children and youth. In S. Frühstück & A. Walthall (Eds.), Child’s play: Multi-sensory histories of children and childhood in Japan (pp. 211–230).University of California Press.

Moore, A. W. (2007). Essential ingredients of truth: Japanese soldiers’ diaries in the Asia Pacific War.The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 5(8).

Moore, A. W. (2021). Children we have lost: Diaries, memoirs, and museum displays of wartime childhood in Japan. Japan Forum, 33(3), 361–383.