In my work on medieval pilgrimage and medieval travel, it became clear to me that the island of Rhodes in the eastern Mediterranean had a very important status in European culture. It was between East and West. It was a hub of western European culture in the eastern Mediterranean, very close to what's now the coast of Turkey, and it was a place very familiar to people from across Europe. It was a meeting point and a melting pot between Eastern and Western cultures, between what we think of as the Byzantine Empire and of the Latin Empire. Rhodes had been on my intellectual horizon for a long time. I had been thinking as well about the transformations of pilgrimage and travel to the Holy Land in the later 15th and 16th centuries, when the Ottoman Empire took lots of the land in the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, including Jerusalem itself, and what this meant for the transformation of travel. I started thinking, what does the island of Rhodes mean? How does it transform in the European imagination? This led me then to my current project on the 1480 Siege of Rhodes.

Medieval propaganda

Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature

- Rhodes was a crossroads of East and West under the Knights Hospitaller, a Western crusading order that protected and cared for pilgrims to Jerusalem.

- After 1453, rapid Ottoman expansion turned Western Christendom into what was perceived as a shrinking world and tightened Ottoman control over vital trade and pilgrimage routes.

- The 1480 siege of Rhodes sparked Europe-wide panic over Ottoman advances. John Kay’s Middle English account may have recorded the first English use of “news” for reports of recent events.

- News and propaganda spread through eyewitness reports, translations, images and compilations like Fasciculus temporum, which blurred history with current events. These sources reveal how power and omission shape narratives and modern fake news.

Across Rhodes

© Porojnicu Stelian via Shutterstock

Knights settle on Rhodes

Rhodes at this time was often described as the key and gate of Christendom, meaning it was the defensive entry point to Christendom from the East, and it was also one of the crucial staging posts between the West and the Holy Land. At this point in the 1480s, Jerusalem had for a long time been a Mamluk possession, so Christian pilgrims and Christian travelers had become used to the idea that they were entering into a Muslim space. From 1453, the Ottomans, based in Bursa and then later from 1453 in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), saw their possessions grow very, very rapidly in what had been the Byzantine Empire, in the Mamluk Empire, and in the Venetian and Genoese possessions in the eastern Mediterranean. Rhodes as an island occupied a quite unusual role here. It was owned by the Knights Hospitaller, which were a Western crusading order that had originally been set up to protect and to care for pilgrims to Jerusalem in the Crusader period.

Ottomans and Venetians, © Hellenic Library - Alexander S.Onassis Public Benefit Foundation

After the fall of Jerusalem, they had moved to Saint-Jean-d'Acre, today's Acre in northern Israel, and after the fall of Acre in 1291, they had been somewhat itinerant for a little while. In 1309 they settled in Rhodes. From Rhodes they built a small empire with a few other islands, including Kos and the little island of Kastellorizo in the far east of the Mediterranean, and their stronghold at Bodrum, Halicarnassus, on the mainland. Really, their empire was not a physical empire; it was a dispersed empire of Hospitaller houses called preceptories, which were all over Europe, and these raised money for and sent knights to Rhodes. They were also involved in land holding, in money lending and in all kinds of relationships with the royal families and the papacy throughout Europe.

A multicultural hub

It was very normal for aristocratic men, often the second or third son of the family, to go to Rhodes and become a knight there.

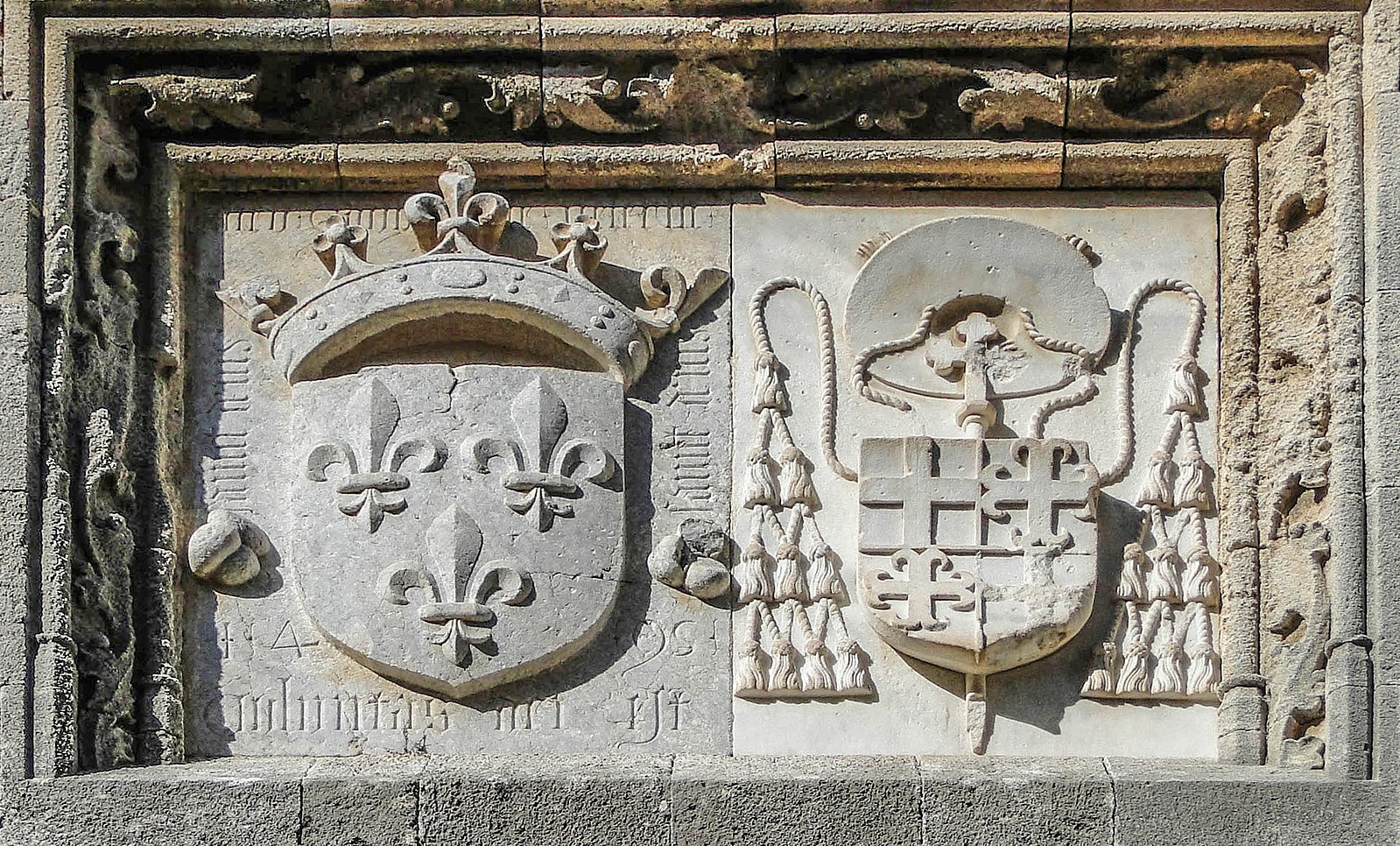

Coats of arms of France and Pierre d'Aubusson, Auberge of the lingua of France, Rhodes © B. Gagnon via Wikimedia

You could think of Rhodes as a United Nations of Western Christendom. Each country or language group had what was called a langue — like the French word for tongue or language — and these were national hostels and military barracks for different groups. An English knight traveling to Rhodes would find other English speakers with particular military roles and English culture, English language, English writing and English customs. It was an international hub for pilgrims, for knights, for travelers, for traders and for bankers across the Mediterranean. Rhodes had this particular importance. It was also, in tactical terms, a stronghold from the Turkish coast. It had magnificent views over the coast. The gap, the sea passage between Rhodes and what's now Turkey is very, very small. Rhodes had a magnificent fortified city, lots of which can be seen today. Rhodes was important both in the Western imagination as a little bit of the West in the East; it was also important to the Ottomans as a western possession right on their doorstep.

The siege of Rhodes

Rhodes – both the island and the town of Rhodes – was owned and controlled by the order of the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights of Saint John, and in 1480, the Ottomans besieged the island from May to August.

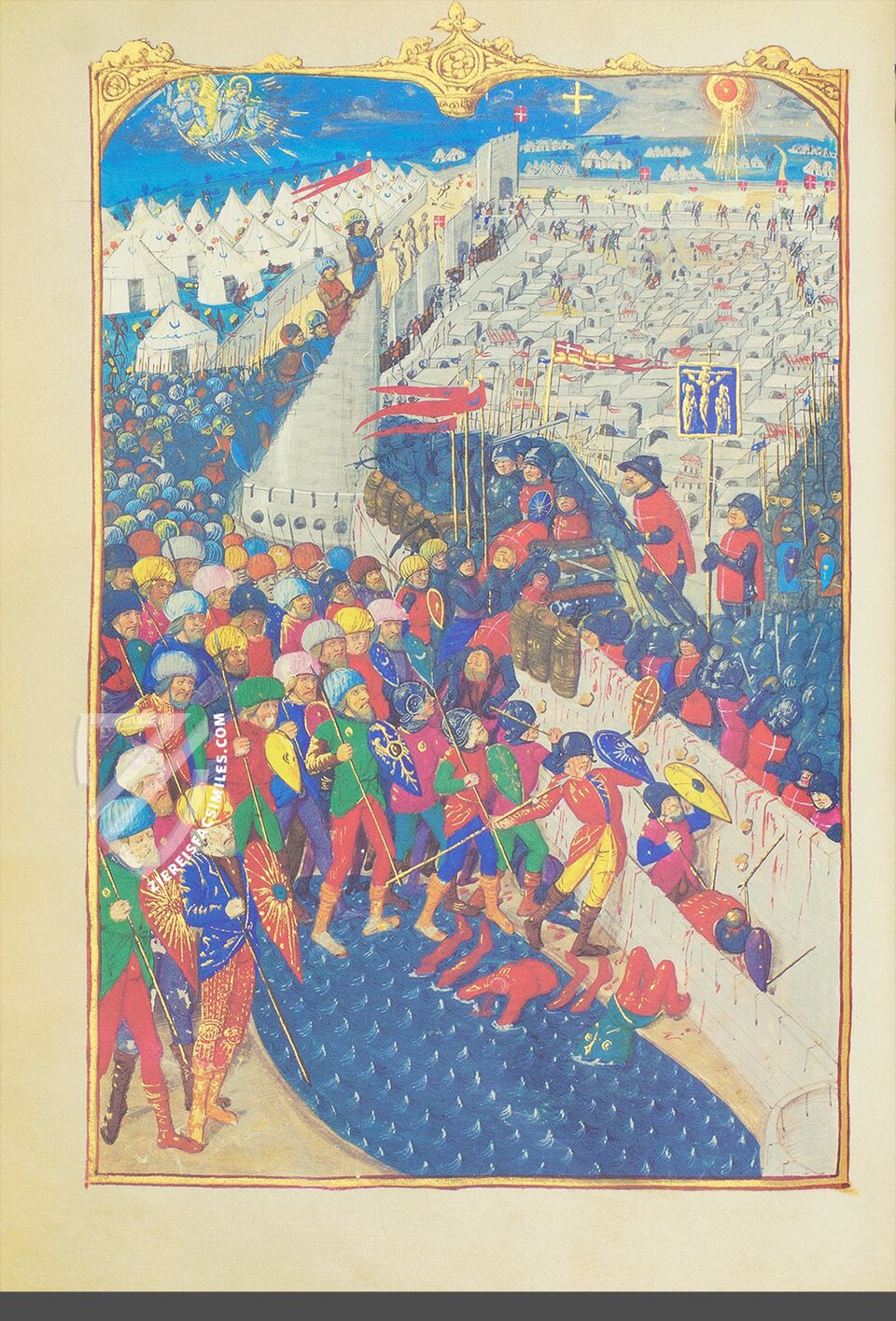

Siege of Rhodes: A Pictorial Account, © Bibliothèque Nationale de France via Wikimedia

The siege was ultimately unsuccessful for the Ottomans, but this caused a widespread panic and outrage in Europe that the Ottomans were advancing on Christendom. This was part of a moment of panic between Christendom and Islam around the encroaching Ottoman forces. I became aware that the Middle English accounts of the Siege of Rhodes had been very little studied, and as a medievalist, one is always looking for these kinds of important texts and important moments that have for one reason or another fallen by the wayside. That's how I got to this. I have now found that there are all kinds of sources, all kinds of materials, all kinds of voices in the period of 1480 to 1522, from Rhodes, about Rhodes, concerned with the ramifications of the siege that I think are really interesting and repay more attention.

A shrinking entity

The year 1480 was a very troubling and difficult one for Western Latin Christendom’s sense of itself. There was a siege of Rhodes, but there was also an Ottoman siege at Otranto in southern Italy, which lasted slightly longer but was basically around the same time. There were rumors that the Ottomans could reach Rome, that this was a transformation of a geopolitical balance of power and centers of power in Europe. Since the fall of Jerusalem in the late 12th century, Western Christendom had often defined itself against a certain Islam which was based in the Mamluk Empire but did not have a territorial claim on the West or did not encroach on the West. With the rise of the Ottoman Empire and the cataclysmic fall of Constantinople in 1453, and the subsequent shift of power to the Ottomans, Christendom has to start thinking of itself as actually a shrinking entity.

The Fall of Constantinople; © Panorama 1453 History Museum, Vivaystn via Wikimedia

By this point, after 1453, Byzantium is really not an empire at all. It’s a tiny rump of itself, and it’s very dispersed — but so are the Venetian and Genoese islands, and what’s now in other parts of Eastern Europe: Bulgaria, Croatia, Slovenia, and Ukraine. The Ottomans had also made very, very significant territorial gains.

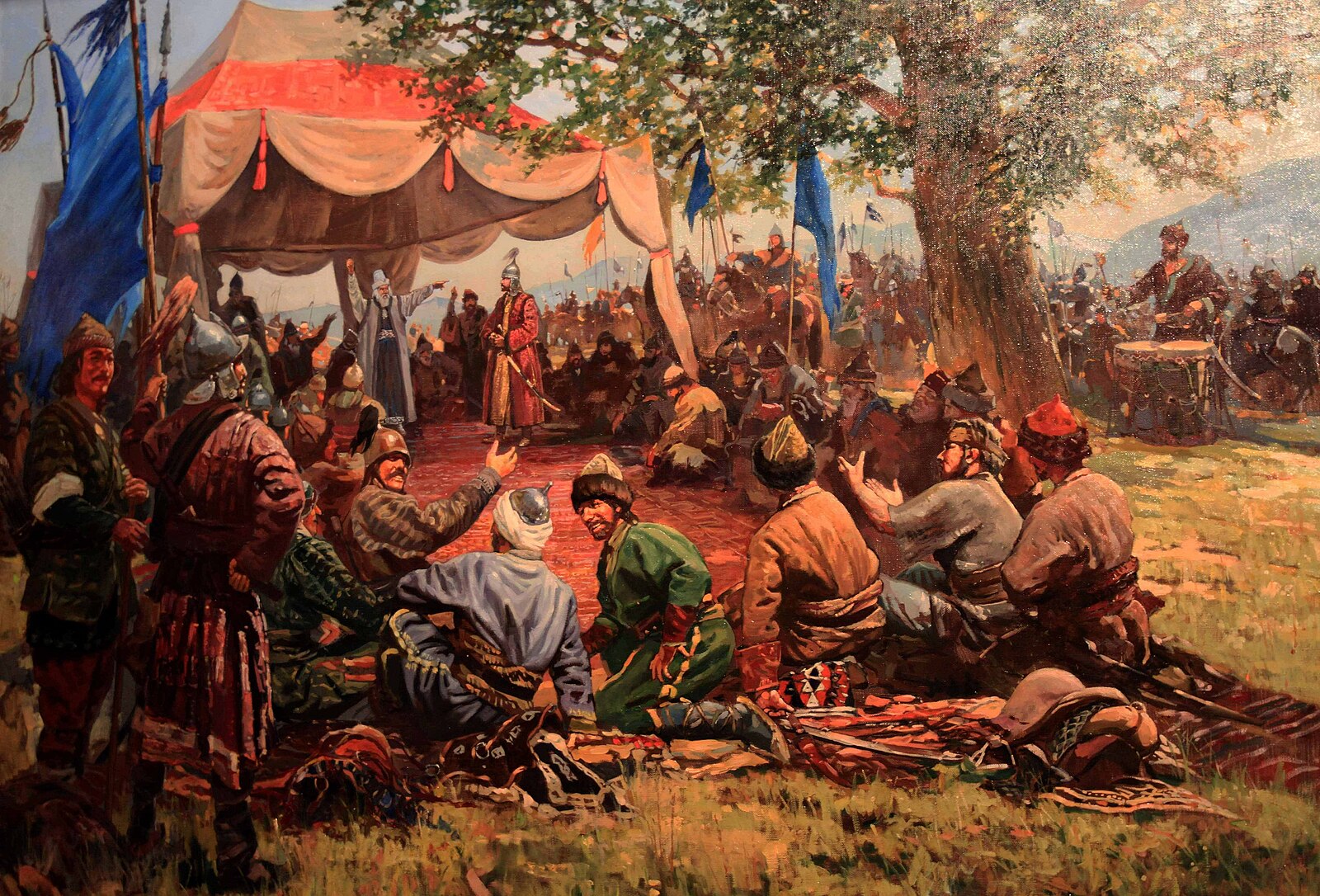

Uniting against the enemy

Christendom starts to think of itself as under attack as the smaller, weaker force. Don't forget at this point as well that the Ottomans have very sophisticated military strategies and weapons and things connected to the Ottoman Empire and to the East more generally: carpets, fabrics, jewelry, spices, things like pitch and alum. These are standard goods traded to the West that the West wants and needs. They're very desirable. They're very expensive. The Ottomans then start to control very important trade and pilgrimage routes. I think we could think of the Ottoman Empire at this point as the superpower.

Mehmed II, Entering to Constantinople, © Fausto Zonaro via Wikimedia

Latin Christendom is very fractured, but it's also under attack. The propaganda really is about what unites Christendom, and the Knights Hospitaller have a really important role in this as a transnational, or supranational, organization. In effect, the Knights are actually, at this point, largely French and are very close to the French crown; that's not the official story of them. The propaganda is about, how do we unite against the common enemy, which is Ottoman Islam, and part of that process is identifying what it is about that enemy that they feel they need to unite against.

Islamophobia in this era

Islamophobia is a useful set of contemporary terminologies and ideas to take back to this period, because at the heart of this is a clash not only between Christianity and Islam in theological terms, but also between different cultural norms, which are often invoked here around alcohol, around pork, around circumcision, around dress, clothing and beards. There's a vocabulary of difference being negotiated in these accounts and partly being invented. At the same time, I think Islamophobia perhaps suggests in contemporary terms something a little more clear-cut than is happening in these medieval texts, because one of the crucial problems for the West is that Greek Christians, Ottoman Turks and other groups in the eastern Mediterranean are unrecognizable or easy to confuse with each other. They don't look necessarily different enough or clearly different.

Foundation of the Ottoman Empire, © Harbiye Askeri Müzesi via Wikimedia

There is lots of slippage in identity at this point. There's a constant theological and practical question in these texts around whether Greeks are heretics or are Christian enough; there's also a question in the text from Rhodes around the Rhodian Jews, that the Jews in Rhodes are presented in the accounts of the siege as being part of the Hospitaller polity, as part of the Hospitaller community, which is at odds in some ways with the historical truth. There is a constant worry about renegades and people converting. How do you spot a Turk? How do you spot a Greek? What is “difference”? That's something that these texts are very, very anxious about. Part of the point of Islamophobia is to make “difference”. These texts are doing that. They're trying to work out what makes this enemy an enemy.

The invention of news

In the Middle English account of the Siege of Rhodes by John Kay, it's one of the first, possibly the first, use of the word ‘news’ in English to mean reports of recent events. This is a transformation in what writing is about. Lots of medieval writing is concerned with old events, with established events, with authoritative events. In the later 15th century, we start to see writing concerned with more current, more recent events. So there's a broader cultural transformation.

This has often been attributed to the printing press, which was introduced in England in the 1470s, but it's obviously spreading in Europe from the 1450s and the speeding up of mediation, of writing. I slightly take issue with that. I think actually this is also to do with a public appetite for shocking, newsworthy, strange, unprecedented events. Part of these are the territorial gains made by the Ottoman Empire in the late 15th century, starting with the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, but first particularly with the Ottoman conquest of Negroponte, Euboea, which is now in Greece.

Siege of Rhodes, Woodcut attributed to Baldung, © The Trustees of the British Museum.

It was a Venetian protectorate, and Negroponte fell in 1470, and this caused in Venice an enormous flourishing of printed and written reports, but also popular stories, songs and a mediated event around the catastrophic fall of Negroponte. This is mirrored and amplified in 1480 with the siege of Rhodes. News follows unprecedented and shocking current affairs. Prior to this, news obviously had traveled. It traveled in letters with heralds, with criers, with popular songs, with popular poetry, but tended not to be tied very recently – so news might travel over a period of quite a few years rather than weeks or months. That's not the case with the Siege of Rhodes.

Fasciculus temporum’s impact

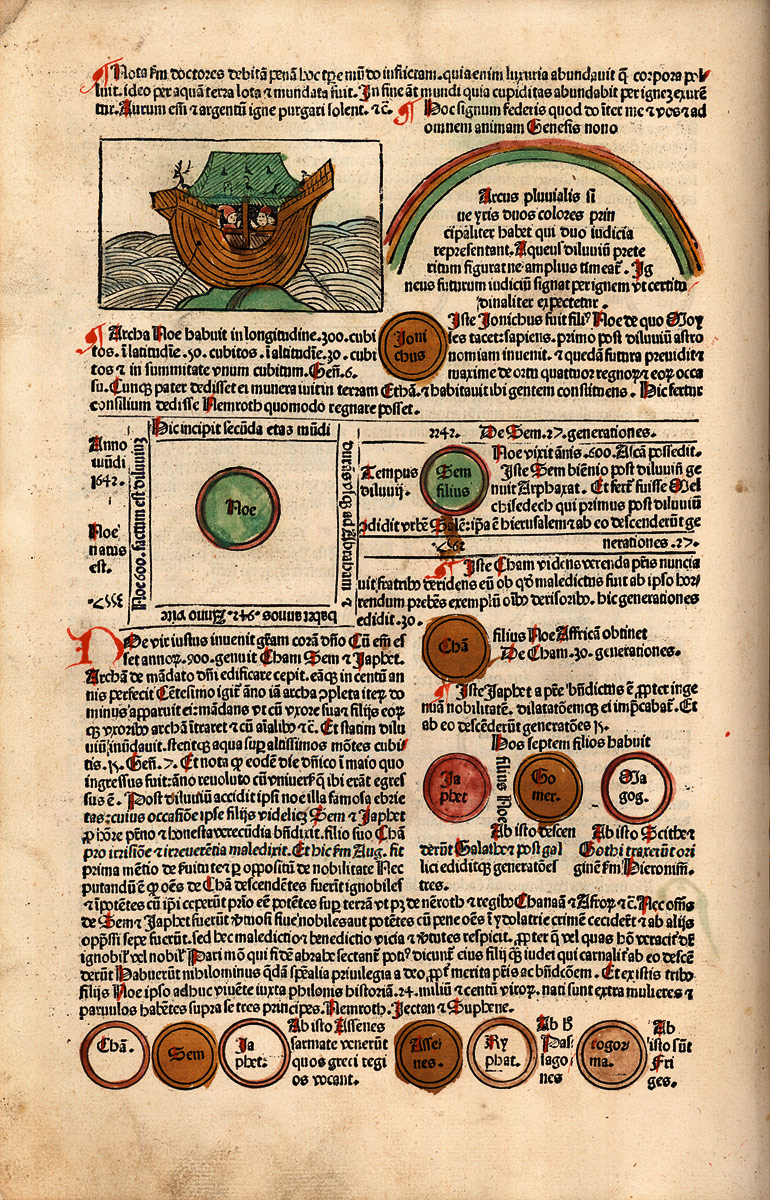

The Fasciculus temporum is a really interesting case in point here. Fasciculus temporum means ‘the bundles of time,’ ‘the gatherings of time.’ The Fasciculus temporum was written in the 1470s by a Latin writer, Werner Rolevinck, and it was a very innovative way of writing about the past.

Fasciculus temporum © Wikimedia

It's sometimes been called medieval hypertext, because rather than being a block of prose writing about the past, it follows several different timelines through the history of the date from creation, the date from the incarnation of Jesus and the pope’s regnal year. So it follows these timelines through it and also has an index, so rather than following time in a linear way, you can choose the different ways you follow time. The Fasciculus temporum is very interesting to me because as well as being a history book, it's also more like a newspaper, because people, including printers and also readers, start to add more and more current events to it, and very often these events relate to what's happening in the eastern Mediterranean. These are readers usually in the Rhineland, in France, in what is now Switzerland, Bavaria and Saxony, but they're also in England, Spain, Denmark and all over Western Europe, reading about how history doesn't just stop in the past, it keeps on continuing. That's when history transforms into current affairs or into news. You can see this bifurcation in the words we have in modern English for news, which is newsworthy, current affairs, but also novel, a novel about a story. These both come from obviously the same root: novelties and novellae. In the 15th century, they're very closely related as a prose account of something unprecedented. The novel goes off in one direction as fiction, and news goes off in another direction as current affairs. That doesn't mean that news writing at this period is always true or accurate. News, as we know, is always biased and always tells one version of events which might be useful to the author or to the audience. This is a moment of transformation in the late 15th century, in the popular appetite, the wider appetite for current affairs and newsworthy reportage.

Influential siege accounts

There were various written versions of the Siege of Rhodes. The most popular one was by Guillaume Caoursin, who had been a participant and an eyewitness at the siege as a senior Hospitaller, and he wrote a Latin account of the siege celebrating the Hospitaller victory very shortly after it had been concluded. It was very widely dispersed.

It was partly dispersed through printed editions in several different countries and in several different languages, sometimes in manuscript and sometimes in translations. My main source in England is John Kay's edited translation of Caoursin's text. This amplifies various parts of the text, adds a preface and describes Kay's own reading of the siege as what he calls news and as a marvel. He presents it to the English King Edward the Fourth. What's clear is that the Hospitallers more generally and the d'Aubusson family and Caoursin wanted to spread the news of what happened in Rhodes as widely as possible and in various different media.

Political and religious imagery

The painting now in Épernay is actually one of the forms of news. This was commissioned by the d'Aubusson family, who were very, very important French Hospitaller knights. Pierre d'Aubusson was one of the head Hospitallers in Rhodes, and his brother, Antoine d'Aubusson, traveled from France to Rhodes to take part in the siege as a military commander, and this painting in Épernay was commissioned probably for Notre Dame in Paris shortly after the siege as an ex-voto, as a thanksgiving description of what happened. It's a very interesting source because it obviously is seen from the victorious Hospitallers viewpoint, but it also shows Rhodes in a way that's recognizable to someone visiting the city today.

Le Siège de Rhodes par les Turcs en 1480 © Hôtel de ville d’Épernay via Wikimedia

What you see in the foreground is Rhodes Harbor, where in ancient times, the Colossus of Rhodes was said to stand over the harbor, and you can see the distinctive moles – those long bits of land stretching out into the sea – which are still there and which had windmills on them in the Middle Ages. On the left hand side of the image you can see a very large number of Turks fighting the knights. That's where, historically, the Ottomans breached the walls, these incredible fortifications that the Hospitallers had built. You can see there the Ottomans penetrating the walls, and that's historically the weakest point in the walls, where the walls came down to meet the sea, and the image at Épernay has a Latin inscription, which is actually taken from the main written account at the time. This image was finished by 1483, within two or three years of the ending of the siege, and this describes how Antoine d'Aubusson was this incredibly brave man, and he went to fight this huge number of Ottomans. Between 70 and 100,000 Ottoman soldiers are thought to have taken part in the siege against a much smaller Hospitaller force. This is actually a religious image, because it describes how the Ottomans managed to penetrate the walls. It was only thanks to a terrifying image of Jesus, John the Baptist, and the Virgin Mary that the Ottomans were so frightened of this amazing miracle — this marvellous intervention — that some of them were converted, and some of them fled in terror. This is thought of as both a political image celebrating the role of the d'Aubusson family and a religious image giving thanks to God for this providential intervention, which then sealed the victory for the Hospitallers.

Rebuilding Rhodes after 1480

After the siege in the 1480s, when the city of Rhodes was devastated, as well as the propaganda being transmitted to the west, the knights rebuilt Rhodes, partly in defensive terms but also in religious terms. They built various chapels and churches and wall paintings, which gave thanks to the Hospitallers’ victory.

Church of the Virgin of the Burgh, Rhodes 14th century, © Jebulon via Wikimedia

There is an area around where the walls were breached near the harbor, where several churches were set up in thanksgiving and as cultic centers for commemorating the Hospitallers victory in religious terms.

Controlling the news

Because in the Middle Ages we don't have a huge number of sources, but we have various competing sources, we can see in quite a lot of detail which particular agents and actors are trying to control the news, current affairs and the horizon of what is news and what is reported. You can actually locate that with particular people like Caoursin, the d'Aubusson brothers and John Kay. You can also then tie that to institutions, including printers, universities and royal families who have vested interests.

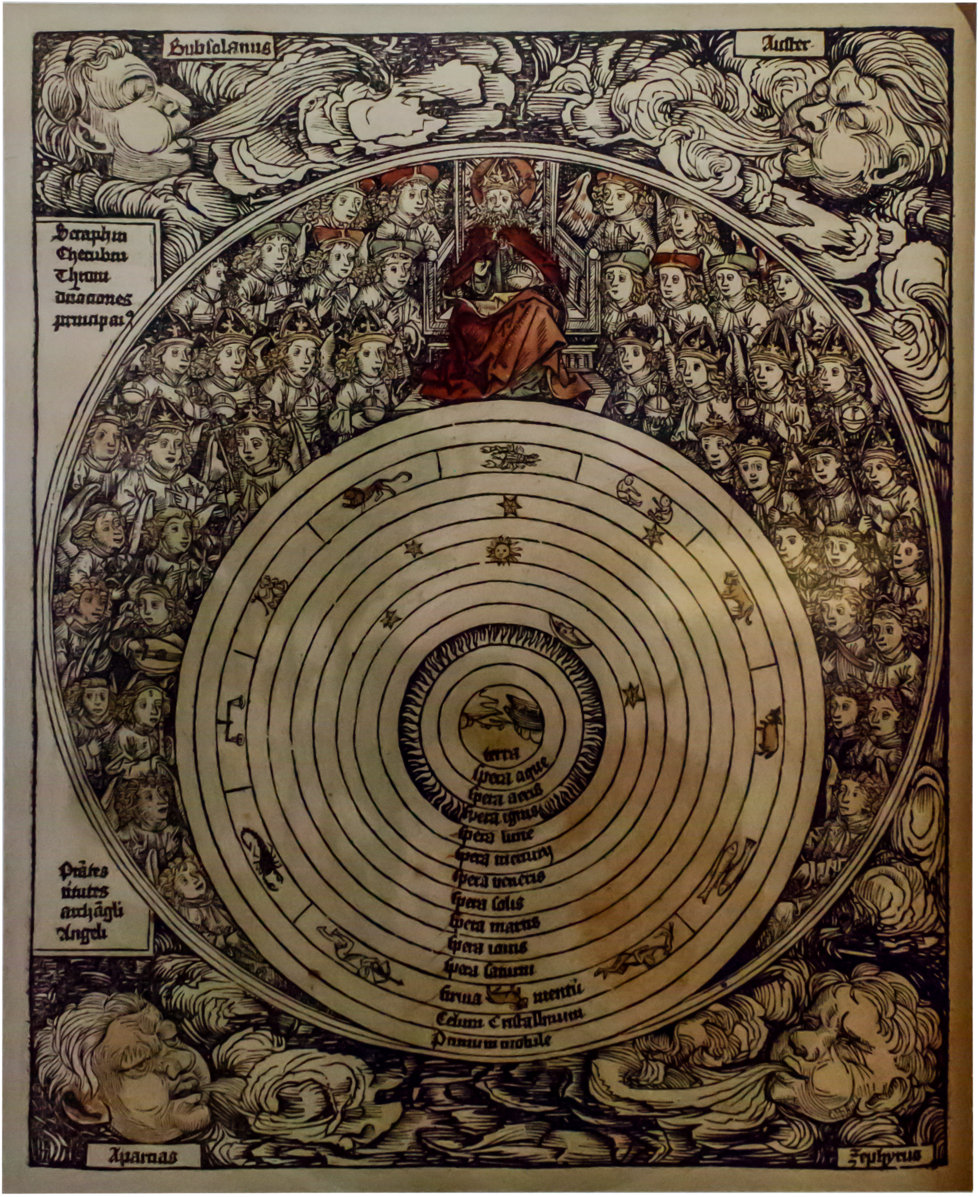

Geocentric universe, Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493 © Hartmann Schedel via Wikimedia

You can reconstruct in quite a lot of detail who has the interest in the news, who has the means to produce the news, and you can locate that in particular moments in time, in cities, in political contexts. At the moment we feel like the internet, and particularly fake news on the internet, exists in this enormous anonymous infinity of tidings, reporting, words and things which cannot ever be located with any agency or any particular specificity. Whereas with this medieval example, we can find out who's actually controlling the news agenda in a particular place and time. That's very important. At the same time, it gives us a chance to ask whose voices aren't being heard, and what don't we know about the siege of Rhodes? I mentioned earlier the role of the Jews of Rhodes. We only really hear a Christian account of that, which I think is probably at odds with the historical experience. If we as readers and as scholars are alert to the fault lines in the news about what's not there, that's, of course, one of the most important things we can do as historians of writing and thinking about the written word. We can actually read between the lines and think not just about truth and falseness, but about who's controlling what we read and who's telling us what we should be thinking.

Medieval news myth

One misconception about the Middle Ages is that news or words were controlled just by kings and monks. Actually, there's a much wider set of media and mediatized reports available through the spoken word, through the written word, through rumor, through religious culture and lots and lots of different people in the Middle Ages are consuming news.

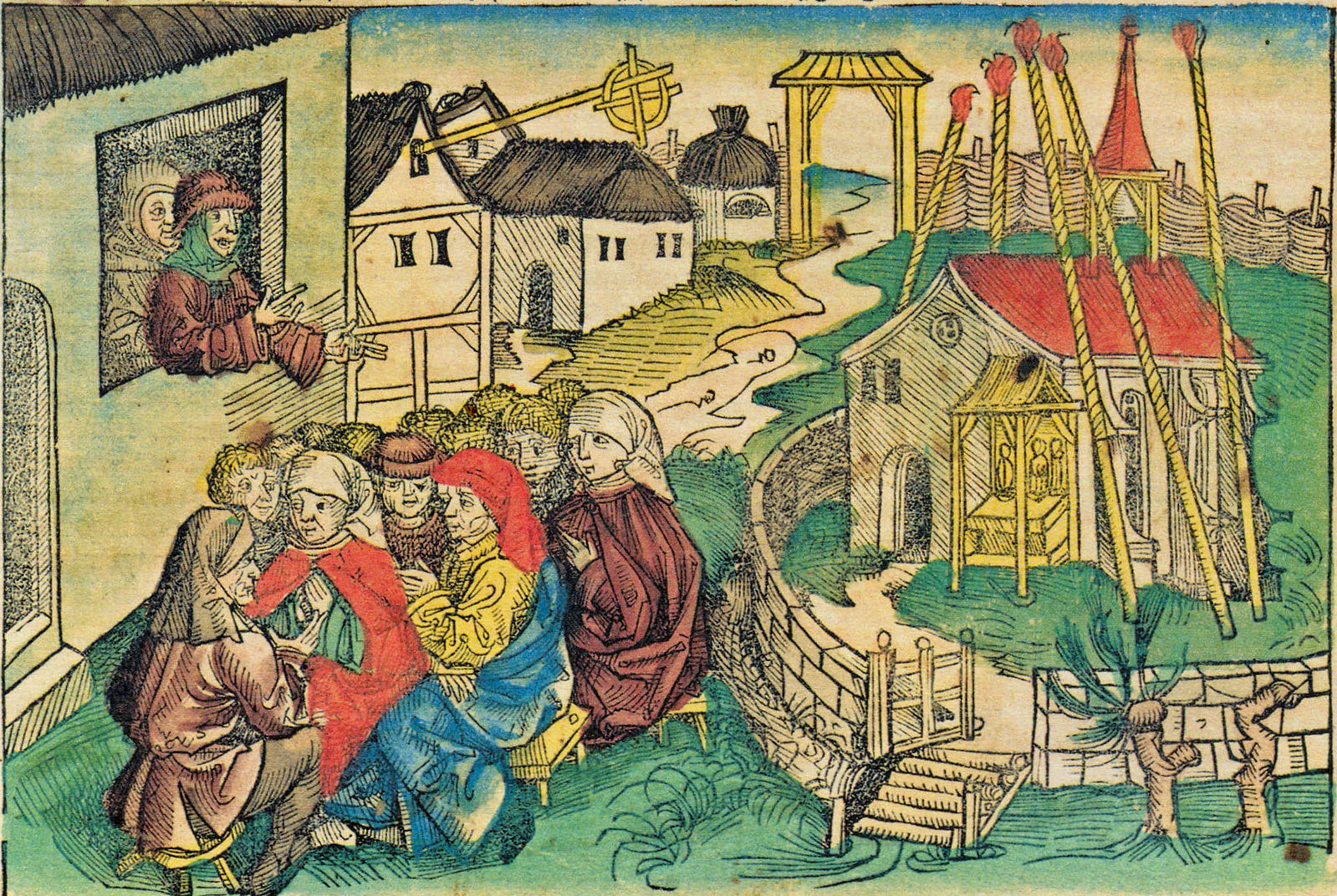

Pawcker von Niclashawsen, Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493 © Hartmann Schedel via Wikimedia

That doesn't mean that they're consuming things that are true, but they're consuming things which are considered politically and religiously useful for them at the time. It's easy to misunderstand the Middle Ages as a time of enormously strong hierarchy, where things were controlled very closely. Actually, from the 14th and in the 15th century, we see not a democratization at all but a much wider range of different kinds of perspectives, controversies and different audiences for the written word than perhaps people give them credit for.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

news in medieval times

Bale, A. (2023). News from the East. Studies in the Age of Chaucer, 45, 3–33.

Bale, A. (2025). Thinking with the renegade. Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, 55(3)

Bale, A., & Sobecki, S. (Eds.). (2019). Medieval English travel: A critical anthology. Oxford University Press.

Bale, A. (2023). A Travel Guide to the Middle Ages. Viking