My previous work on the burning of Jews and my later work on the threats to burn Margery Kempe also then connected with understanding how somebody could be put to death by burning for witchcraft in the early 14th century.

The invention of the witch

Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature

- The story of Alice Kyteler and the witchcraft allegation of 1324 helped crystallize the church's new view that magic was heresy, and it shaped the later stereotype of the witch.

- The trial is not simply a story set in Ireland but one about how the church at a particular place and time invented its enemies.

- The record alleges secret gatherings, diabolical pacts and harmful magic; Alice escaped, but one of her co-accused was burned at a period that coincides with the festival of Halloween.

- Witchcraft accusations flourish in stressed communities and spread through rumor or gossip, causing real harm. Modern portrayals often sanitize the witch, despite misogynist origins connected to violence against women and their erasure.

The story of Alice Kyteler

I've been intrigued by the story of Alice Kyteler and the witchcraft allegation of 1324 for a long time, partly because it's another one of these stories from medieval England that has not received the attention it deserves, and also because it intersects with lots of my other interests around women's voices — popular religion, histories of persecution and cruelty, and the role of written material in creating historical circumstances and historical precedents. Alice Kyteler was a woman in early 14th-century Ireland in the town of Kilkenny, which was then part of the Norman English colony in Ireland. She was accused of witchcraft, along with a group of other people there. Ultimately, what drew me to this story was that we have one written account of it – so part of the historical record is around the role of a written piece of evidence – but also because this allegation led to the burning of one of the accused women.

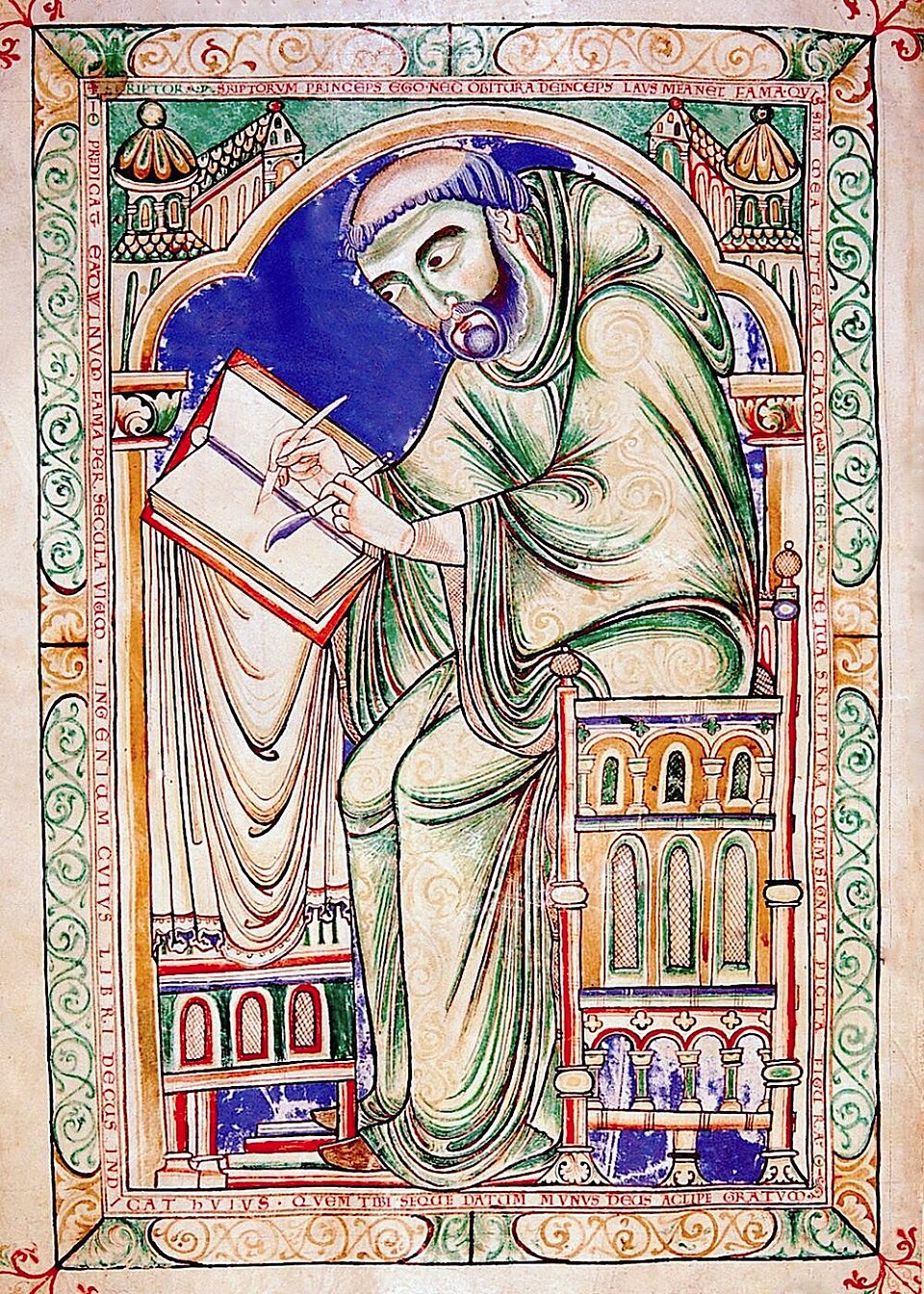

Psautier d'Eadwine © Trinity College via Wikimedia

Wealth and frontier tensions

The allegation of witchcraft took place in the town of Kilkenny in 1324. Kilkenny, at this point, is the second town of Ireland after Dublin in the English colony there, but it's also very much a frontier zone. It's an entirely English town, but about 10 to 15 kilometers away the Gaelic Irish population was living and had earlier been expelled from Kilkenny, and this is really the very edge of the English Norman area of control. Alice Kyteler was one of the wealthiest people in medieval Ireland, and in 1302, again in 1305, and around 1316, she'd been involved in various allegations around expropriating money from her stepchildren and other financial irregularities.

Christine de Pisan and her son © British Library via Wikimedia

This is an important backdrop to the allegation of witchcraft, as she was extremely wealthy: she had been married four times. She had been in conflict with her stepchildren and her wider family before the allegation of witchcraft took place, and she was also living in this quite tense political situation at the edge of the English colony.

An unprecedented allegation

In the later 1310s, the colony was hit by a series of disasters: the Scottish invasion, which was very disruptive and very violent, famine, an affliction of the animals and various kinds of social tensions. At the same time, a new bishop arrived in Kilkenny, a man called Richard de Ledrede from Avignon. He was directly appointed by Pope John XXII, and it was he who accused Alice Kyteler of witchcraft.

A witch and her familiar spirits, 1579 © Wikimedia

This was an unprecedented, really original allegation, not just in Ireland but in Latin Christian Europe. Kyteler herself denied the allegations, and she had a variety of very influential people around her who also denied the allegations. The source we have for understanding this is the account of the case written by Bishop Richard de Ledrede afterwards, or written for him, and probably designed to be sent to the Pope in Avignon. It is a very important case in thinking about how a bishop, and how the church more broadly, was constructing witchcraft at this time.

A diabolical pact

This is a very well established fulcrum or moment in a transformation of the church's thinking about heresy and magic. Other historians have written about this in a lot of detail, that the papacy in Avignon at the time, particularly led by John XXII, developed an idea of heresy which embraces magic and an idea of magic which is itself inherently heretical. The difference here is that earlier magic had been understood as being wayward if it was malicious in intent — an error, but ultimately a kind of fantasy, a mirage induced by the devil. Under the papacy of John XXII, it actually comes to be seen as a diabolical pact that the magician or the witch makes with the devil, and the magic is itself efficacious; it can harm. We see this being tested in the trial of the Knights Templar, and in part some of the trials in Languedoc at the time, but it really achieves its first form around witchcraft in Kilkenny, in the trial of Alice Kyteler and her group.

Templars Burning © British Library via Wikimedia

It's part of John XXII’s battle against heresy and his vision of theological uniformity at the time, and it's also part of a restriction in Christendom around who's in and who's out. There are, at the same time, campaigns against Jews, the Knights Templar, female midwives from practicing as midwives, alchemists; Richard de Ledrede would have seen some of these attempts at theological uniformity, and he probably would have seen the burning of Marguerite Porete, the mystic in Paris, a few years earlier, as well as some of the burnings taking place in and around Avignon of John XXII’s enemies. We need to think of this not so much just as an Irish story, or as a story taking place in Kilkenny, but as a story about how the church invented its enemies at a particular place and time.

Jealousy and rumors

In the trial record, the activities that Alice Kyteler and her group are accused of are absolutely the standard kind of allegations that have subsequently become identified with witchcraft. At the time, they were not standard at all. She is accused of meeting at a crossroads with a group in secret. At this crossroads, they made various spells and potions in the skull of a robber and used the dead bodies of babies that had not been baptized. They also met with a devil, a demon called Robin, and he sometimes appeared as a cat, as a black dog or as a black Ethiopian African man, whom they worshipped, whom they made false church services with, mocking the ceremonies of the church, and whom they tried to harm other people with.

Witches' Sabbath © Hans Baldung Grien, Metropolitan Museum of Art via Wikimedia

Alice herself was accused of casting spells that turned the women of the town into having faces like goats and also of sweeping dust to her door while saying a spell which turned the filth of Kilkenny town into money. That's how she got rich. To answer the question about why she was accused of witchcraft at this time, the kernel of the accusation is that she had had three husbands who had died, and each time she had gotten richer while the husbands’ children had been disinherited in favor of Alice and her oldest son.

Suspicion and inheritance

At the time of the trial, her fourth husband was said to be ill, lying in bed, poisoned by Alice. His fingernails had fallen out; his body hair had fallen out, signs of poisoning, and he had found a bag of magical ingredients and preparations, which he'd given to some friars who then accused her of magic. At the heart of the allegation is financial jealousy and arguments about an inheritance. Had she poisoned her first three husbands? Possibly. If that were the case, why wasn't she tried for homicide, for murder? There is jealousy; there's spite; there's envy. She's incredibly wealthy. She's also of Flemish origin, so she might have been considered something of an outsider, but at the heart of this, I think there is a disputed inheritance, and the witchcraft allegation is applied to her as a disruptive, rich woman who has taken something that other people think she shouldn't have.

The idea of a witch

We're right, at this point, to talk about the invention of the witch, because the witch, as she is subsequently identified, including her gender as a woman, really crystallized at this point. There had been many different previous kinds of witch all the way back to ancient Greece. In the Hebrew Bible – where you can read about the Witch of Endor and other kinds of sorcery and prohibitions on sorcery – and then right up to the early 14th century, we find people being accused of witchcraft. There is a kind of flurry of accusations around witchcraft in 1302, in the English city of Exeter. Often, in the very famous trial accounts of the Inquisition that Emmanuel Leroy Ladurie wrote about in Montaillou, people will be accused of different kinds of magic, involving herbs, spices and food, as well as poisoning or bits of bread and wax effigies. There’s a kind of witchcraft circulating at this time. What isn't yet established, and what really crystallizes in Kilkenny, is the identity of the witch. In the historiography of witchcraft, historians of witchcraft talk about the kind of standard image of the witch as it crystallizes in the 15th century in The Hammer of Witches, which is a very famous inquisitorial handbook for identifying and prosecuting witches.

Weather Magic © Ulrich Molitoris via Wikimedia

These include things like aerial flight, harmful magic which harms babies, other kinds of harmful magic, making a sexual pact with the devil and having a secret coven. All these things are present in the allegations against Alice Kyteler. The crucial thing here is that this is a very early, and possibly the earliest, case where the witch, as she becomes known, is prosecuted as a witch. It's not incidental to a heresy case or incidental to a murder case. It is actually what she's prosecuted for: being this idea of a witch. At all points, Alice Kyteler and her allies deny this, and I think to them this was an outlandish, imported idea of it. At one point, one of her defenders says to Bishop Richard de Ledrede, how dare you come to Ireland, a land known for its saints, an island of saints that has never harbored heretics, and accuse us of this ridiculous allegation? There is a real mismatch between what Richard de Ledrede thinks a witch is and what the people in Kilkenny perhaps think it is.

How the case unfolded

The story unfolds in a very complicated way, which the account written at the time goes into a lot of detail about, because Alice is first accused of witchcraft, and she is defended by the legal authorities at the time – who also happened to be related to her. She does something very clever, which is to counter the allegation of witchcraft by accusing Bishop Richard de Ledrede himself of slander, and he himself ends up being imprisoned for a couple of weeks in Kilkenny. We get this quite long process of allegation and counter-allegation, during which time Alice seems to be at large. Eventually, the other Irish bishops agree to support Bishop de Ledrede's allegation, and Alice is put in prison, first in Kilkenny and then in Dublin. From Dublin, probably in Dublin Castle, Alice escapes, and we don't know where she goes. She escapes by being well connected; she has married into some of the richest and most influential families in Ireland at the time, Norman families, and she disappears – probably to England, but we don't know where. She effectively goes legally unpunished, but obviously she had to give up her wealth, her standing, and her life. And that’s a very intriguing — and very shocking — moment, really, that she disappears.

Aftermath in Kilkenny

One of her co-accused, a woman called Petronilla of Meath, is prosecuted and burnt in Kilkenny on November 3, 1324, and this date seems to be chosen because it coincides with the festival of Halloween – All Hallows – but also with the pre-existing Irish festival of Samhain, which is also a kind of festival of bonfires. It's a festival of meeting the souls of the dead, and it's what then contributes to the modern understanding of Halloween. It's a moment when the veil between the living and the dead is at its thinnest, and the souls of the dead are likely to reappear from purgatory.

Sculpture: "Dame Alice Kyteler and her maid Petronella" © Kevin T. Fennelly

The timing of the burning of Petronilla seems to be directly connected to these older ideas — about the changing of the seasons, about festivals of fire, about the darkness of the season, about the proximity of the souls of the dead, and about sacrificing Petronilla, in a way, at a particularly paganistic moment.

Lessons from the case

The witch didn't always exist in a readily identifiable stereotype, and this moment in 1324 is a crucial moment of that stereotype coming into being. One of the reasons I'm working on this case is because people often say to me, ‘There were witches all over the place in the Middle Ages,’ and that's not true at all. The witchcraft burnings, the great persecution of witches, really takes off and takes place in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries.

Torturing and execution of witches © Wikimedia

This is an unusual outlier. It's a very early case. What it does share with later witchcraft allegations, which is very important for the present day, is that most witchcraft allegations take place in communities that are already under stress and already have disagreements in them. The allegation usually starts with rumor or gossip, with what we might also think of as fake news or misinformation. It's very important to understand this case and to understand similar things happening in the present day, that rumor and gossip are not things which don't have an effect. It's not something which exists just as language. It's something which actually can then cause things to happen to real people and cause legal and formal processes to be launched based on unofficial or unreliable words themselves.

Very dark origins

I'm very troubled, having spent so much time thinking about witchcraft, that the witch not only remains very much a presence in modern ideas, a modern repertoire of stereotypes, but witchcraft trials are still taking place in the world today. In Papua New Guinea, there have been people burned in the last few years for allegations of witchcraft. Also, the witch, somehow in Western culture, has been rehabilitated as a children's character, and, at Halloween or with various children's cartoons and books, the idea of the good witch, the nice witch.

© Shutterstock

I think this is somewhat problematic, because the witch comes out of a deeply misogynistic, deeply anti-feminist ideology of the Middle Ages and is very much connected to violence against women and the erasure of women. If we're going to rehabilitate the image of the witch for children and for popular culture, we also need to understand its violent and very dark origins.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

accused women in the Middle Ages

Bale, A. (forthcoming). The first witch. Viking.

Bale, A. (Trans. & Ed.). (2015). The book of Margery Kempe. Oxford University Press.

Le Roy Ladurie, E., Bray, B. (Translator) (1975). Montaillou, Cathars and Catholics in a French Village 1294-1324. Penguin.