A collective experience of reality

Right from the first drawings on cave walls, we see art as a way of encapsulating, crystallising, making experiences through our eyes and capturing them in a permanent form. If you were brought up a Catholic, like I was, all the images in your prayer books and on the church walls would have been of things that you can’t see: angels, heaven and visions of saints. They saw ecstatic visions that have now become historical events such as the Crucifixion or the Resurrection of Christ. This mesmerised me when I was young. The Crucifixion, though it may have happened, spurred painters to bring their imaginings to reality for a collective experience of what we feel is real.

The second aspect of the invisible that has been made present and realised by art is the state of the inner mind. The psychological states – dream states, hallucinations, nightmares – run from Bosch through to Goya, right up to the present day and the enquiries of the Surrealists, whose interest in art was to depict what can’t be seen, the experience of human consciousness, what lies beyond empirical testing.

What art seems to deploy is ideological. Art is the great carrier of meaning in the public sphere. The way I look at art will always carry some kind of social or political weight and burden, even the most personal landscape in watercolour, underneath its apparent surface of pastoral prettiness.

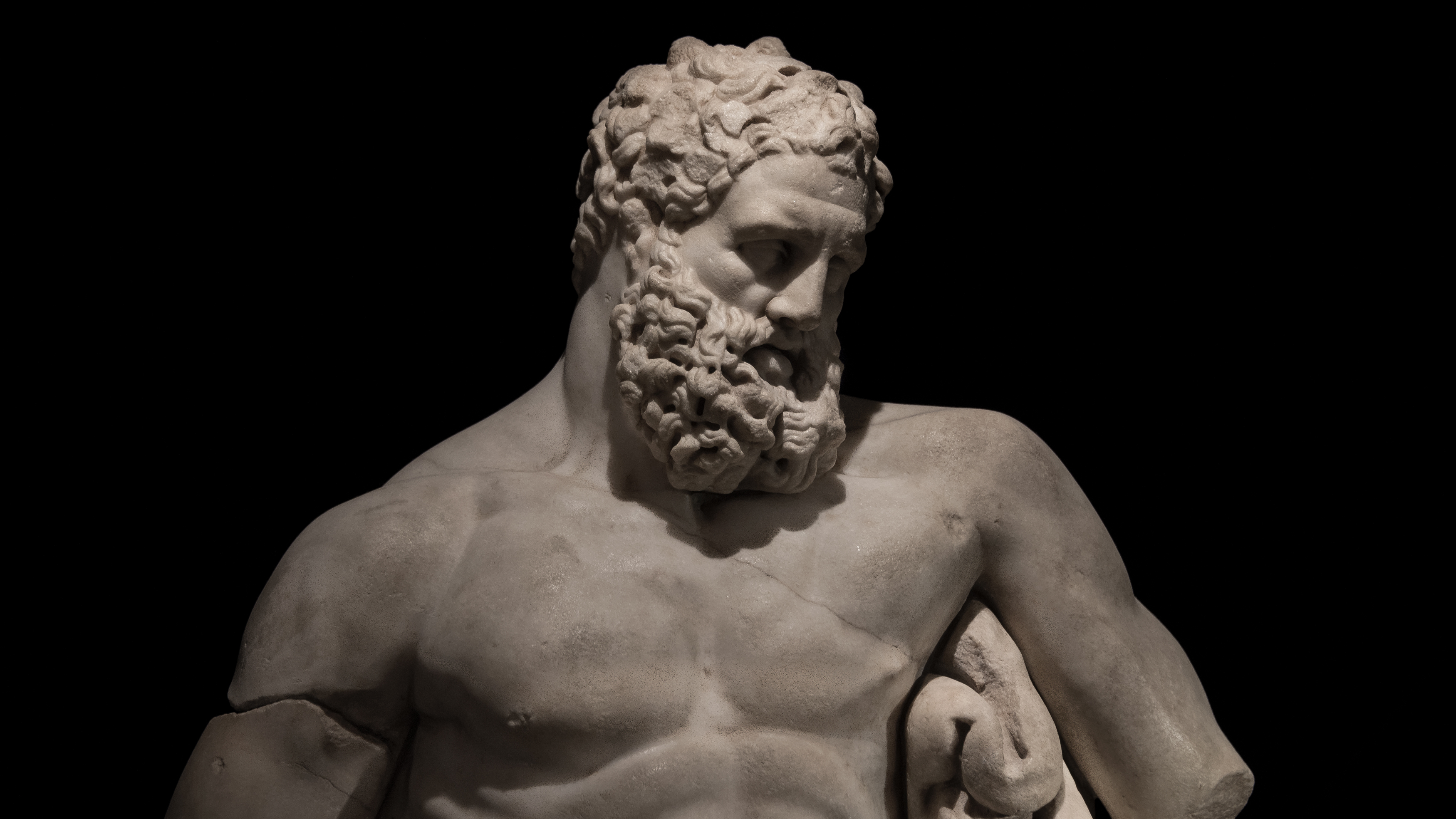

This is a school of art criticism called cultural materialism. It’s also anthropological because it’s related to the way we look at one another. In a museum vitrine, works of art made by a certain people or tribe in the past are admired for their beauty, for their manifest aesthetic qualities, for their craftsmanship, skill and so forth, but also as evidence of what those people believed, followed and aspired to, how they conceived of their gods and what qualities their gods had.

The way the images entranced me as a child later revealed to me that they were actually carrying a very strong weight. The many Madonnas and Child are known as some of the most beautiful paintings in the world. I began to see that these paintings by Botticelli, Raphael and others were designed to hold up to me an image of virginity and motherhood, and a possible amalgam image of perfect motherhood and femininity; an image of docility, acquiescence, subordination to the idea of maternity, to the idea of the child and so forth. I think this idea runs through a great deal of image-making, often unbeknownst to the artist.

Artists are often the unwitting tools of prevailing ideology, and one has to live in constant vigilance against accepting those conventions and going with them. For me, one of the tasks of art is to try and see its own ideological ballast and try and upset it, but that’s moving forward too much in time and too much to what contemporary artists are doing now. I would say that the human species is pretty much hardwired to enjoy art. It differentiates us as humans from animals. Some animals, like bowerbirds, make beautiful things; however, we’re not certain that they make them in the interests of beauty.

On the whole, it’s a mark of the human to respond to images. If you think of a child’s development, the child will be able to enjoy pictures and actually recognise pictures very, very quickly, long before they learn to read. And they will make, as Picasso pointed out, the most remarkable images themselves.

What we can learn to look at is the significance of art. We can also attempt to understand its power and very difficult, packed concepts like beauty. I began to think, I must stop and look at what I mean by beauty, because, of course, you also need to look at what you mean by ugliness. This often has moral valence. Art uses ugliness to denote evil and that needs to be examined. Devils are characterised in pictures from the Middle Ages onwards as somehow deformed and that needs to be thought through and challenged, too.

However, we can learn to look at art as a great pleasure and a collective process. One of the things that’s happened in recent times – since I was a young woman in London – is that contemporary art has become a social event. People like going together to art galleries and to shows. I’ve started going to one or two exhibitions in lockdown and it’s quite remarkable how many people there are, from different generations, masked, keeping their distance and often very quiet, because it’s difficult to talk through a mask. This has increased the intensity of the experience and the pleasure of actually being in touch with something people have made. We’re a maker species and the representations we make, whether they are fantasies or of the inner or the outer world, are a mark of our inner lives as people.

The Greeks had a concept they thought of as the high principle of art: which was that art should aim towards energeia, a kind of quality of living likeness.

They associated it with accurate representation so that something looked real. Their highest example was birds pecking at a painting of a bunch of grapes on a wall, mistaking it for a real bunch of grapes. That was the idea of this living energy: that there is a quality of vibrant power coming out of a work of art. We are perfectly aware of it as a society now – a modern society – because advertising is still the largest source of revenue. Why? Because of images; coupled, of course, with messages. Yet, the messages, when they flit past us on the web, are not as important as the images, which have a lingering power that’s subliminal. We don’t even know that it’s happened, that it’s affected us, so it’s connected to studies of hypnosis ; the image, as it were, emanating current forms into our consciousness and imprinting us.

An archive of a vanished world

My first outing of lockdown was to the National Gallery to see the Titian exhibition; there was a portrait there by Jan Gossaert (also known as Mabuse) of a little girl, which enthralled me. The artist had rendered the little girl at one point in her life. He had caught her before she became the person she became. It wasn’t even a portrait of a person yet but of a child at that stage. It was so sensitively done, with such care to her individuality. The power it had over me linked me to someone vanished.

There is that aspect of art that it is the chronicle and archive of a vanished world, of all these vanished faces, these vanished people, these vanished situations, vanished countryside and so on. Without these representations, how much would we know of the past, of what the past looked like or what the past imagined? This portrait at the National Gallery made me feel that he had looked at her with sympathetic concentration, which is a kind of mode of the way we should look at one another. It involved me in a relationship that wasn’t a relationship. They weren’t related – she wasn’t his daughter – it was a commission. Nevertheless, the quality of his attention was exemplary, which underlines the point that making a drawing is an act of attention and that attention is in itself valuable, valuable to one’s relationship to oneself and to the world. It deepens and stretches us. The other important thing about this painting as an example of the power of art is that it establishes a connection. They think the little girl was the princess of Denmark. Mabuse (Gossaert) was a Dutch painter, and this is another way in which art not only communicates beyond language and establishes a rapport with each of its viewers through this non-linguistic form that it takes, it’s also a circulating body of knowledge across borders.

I would be sorry if the current need to repatriate objects, to which I’m sympathetic, meant that we all ended up with our national collections only. I really love the fact that art is in itself polyvocal and multi-ethnic and doesn’t have a homeland; it just travels. It travels regardless of people’s blood or ethnicities, or it speaks across these borders. The power of art has increasingly become the mode of challenge.